Last week’s trip to Albania being too mainstream, this edition of Railway Review (how I yearn for the return of Question Time!) was going to be of an obscure South American mineral line. Observing the date, one felt obliged to comment upon the patron saints of the poblacions along the route. Whereupon, I went full Easter hols and under divine inspiration asked my assistant, Miss A.I. Chat, if she knew of any stations that could be shoehorned into a Holy Week article. As ever, her response was somewhat eclectic, but sent me down another one of those enjoyable railway research rabbit (Easter Bunny?) holes.

Bunny

Yes, there is a place called Bunny. A village located in Nottinghamshire, it sits seven miles south of the city of the same name. At the western extremity of the parish, Bunny lies only 400 yards from the old Great Central Railway. Nearby, what should have been Bunny Sidings was known as Gotham Sidings, as a junction there took a short and meandering branch to the long-gone Gotham limestone and plaster works. The route is now covered by a road called Gypsum Way.

Another gypsum facility still exists at East Leake, beside the Rushcliffe Halt station on the preserved Great Central Railway (Nottingham) line. The road from East Leake is called Bunny Lane and provides a view of a GCR overbridge en route, complete with an impressive telephone pole.

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

Calvary

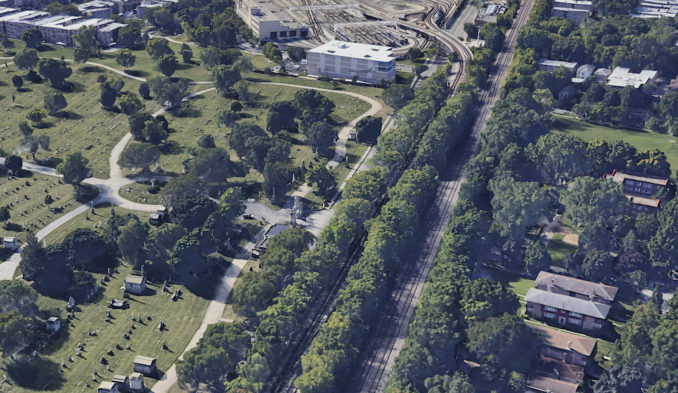

On this day all those centuries ago, the road of Our Lord led to Calvary. And there is, or was, a Calvary railway station on Chicago’s L line. Opposite the entrance to the Calvary Cemetery in the north of the city, the station operated on the Evanston branch of the North Side Division of the city’s Purple Line.

Established on 16th May 1908, it closed in 1931, being replaced by the South Boulevard station. Despite being on the elevated railway, the Calvary was at ground level and consisted of a simple wooden structure on the west side of the tracks between St. Paul and North Western. From there, it is 400 yards to the L’s Howard depot and a further 400 yards to Howard station, where the L becomes an elevated railway.

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

In the centre of the photo, we see the ornate entrance to Calvary Cemetery. To the right is the un-elevated L line. To the right of that is the main line. At the top, we see Howard Depot, where the L trains are stabled and serviced. During his previous life more interesting, your humble author was oft out and about in Chicago. One day, he boarded the wrong L train and visited Chicago’s South Side by mistake. Bit rough around there. Which brings us to:

Easterhouse

As regular readers will be aware, my father served in the Royal Engineers during a career spent in construction. One of his more challenging missions was to go to Glasgow to deliver the tenders required in anticipation of the rebuilding of the ‘multis’ in the city’s Easterhouse estate. I accompanied him, not to peruse gift shops and antique stalls that might lie between an Easterhouse Cathedral and an Easterhouse Castle, but to guard the car.

Located on the North Clyde Line, Easterhouse railway station serves as a key suburban stop. Opened on 1st February 1871 by the North British Railway as part of the Coatbridge Branch, this line connected the industrial towns of Coatbridge and Airdrie direct to Glasgow – facilitating both passenger and freight transport. Located 5¾ miles east of Glasgow Queen Street, Easterhouse features two platforms and is managed by ScotRail. The current buildings reflect a modern design and replaced the original structures during redevelopment efforts in the mid-20th century.

The surrounding area experienced significant transformation in the decades following the station’s inception. Once a rural village, it evolved into a large housing estate in the mid-20th century, aimed at addressing Glasgow’s housing shortages. The multi-storey flats were part of a post-war housing initiative aimed at relieving overcrowding. Constructed in the 1950s and 1960s, these high-rise buildings seemed a modern solution to housing shortages. However, many of the structures suffered from neglect, poor maintenance and social problems, leading to a decline in living conditions.

As for my father’s heroic efforts with the multis, he needn’t have bothered. Likewise my own risking of an air rifle pellet through the skull while tenders changed hands on a brisk Glasga afternoon. By the early 2000s, a substantial portion of the housing stock was derelict and uninhabitable, with one in eight homes standing empty. In response, Glasgow City Council initiated a comprehensive programme focused on demolishing the deteriorated tower blocks and replacing them with smaller, more sustainable housing.

The regeneration efforts have been extensive, attracting over £400 million in public and private investment over the past two decades. This has facilitated the construction of around 3,000 new dwellings and the development of amenities such as the Glasgow Fort shopping centre, which enjoys 14.5 million visitors a year.

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

Judging from the safety of my own home via Street View (you don’t think I’m ever going back?), the place is improved, but the station – down the steps to the left – still requires quantities of spikes and razor wire.

Eggborough

Which brings us to Easter Sunday and the symbolism of resurrected new life provided by the egg. Unfortunately not so Eggborough, now a deserted branch line terminating at a demolished power station. Located in North Yorkshire, the Eggborough branch line dates from the 1960s and coincided with the construction of the coal-fired power station. The branch line’s function was to facilitate the delivery of fuel to the power station from various collieries across Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire.

Trains bringing coal would arrive via the main line, enter the branch, and be unloaded at the power station’s rail sidings. These sidings were extensive and designed to handle a continuous flow of wagons through the merry-go-round, or MGR, process. Eggborough Power Station ceased electricity generation in 2018, marking the end of regular traffic along the branch. Since then, the future of the line has been uncertain, though parts of the railway infrastructure remain in place. There have been discussions about redeveloping the site for new industrial or energy-related uses, which might include repurposing the branch for freight access once again.

While not as well-known as other lines in Yorkshire, the Eggborough branch is a typical example of the many industrial rail connections built in the mid-twentieth century to serve Britain’s power stations. These lines were integral to keeping the lights on during a time when cheap local coal dominated the UK’s energy mix and provided low-priced, reliable electricity to both industry and the householder.

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

In the top photo, we are looking down the abandoned, part-flooded branch towards the power station. The road bridge carries the A645 before it joins the A19 at Eggborough a few hundred yards away. The bottom image shows the remains of the power station. To the left is the footprint of the demolished cooling towers and to the right the large loop is of the merry-go-round coal discharging system. Below that is the curve and straight which took the Eggborough branch to its junction with the Pontefract to Goole line.

The Vatican

Beyond death and resurrection lies the promise of the life eternal. But what do you give the man who has everything, even the Keys to Heaven? A railway. Many a man of a certain age has his own model layout, but the Pope’s – as is befitting of a Pontiff – is 1:1 scale. The Vatican Railway, or Ferrovia Vaticana, is one of the shortest and most unique lines in the world. Located within the boundaries of Vatican City and constructed during the 1930s, it was a product of the Lateran Treaty.

This 1929 agreement established Vatican City as an independent sovereign state and included provisions for a railway connection to Italy’s national network. The branch line is 300 yards long and connects the Vatican to nearby Roma San Pietro on the Italian side via a short viaduct and a set of gates in the Vatican wall. The station inside Vatican City, Stazione Ferroviaria Vaticana, features an elegant building with a single platform and a covered portico, suitable for receiving special guests or ceremonial visits.

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

The railway was planned to facilitate both passenger and freight transport, but regular passenger services never materialised. Instead, it has functioned to transport goods such as coal and supplies. A couple of freight wagons can be seen in the siding in the photograph above. Its most famous use came in 1962 when Pope John XXIII became the first Pontiff to travel by train from the station, and subsequent popes have on occasion used the line for symbolic journeys. In modern times, the railway is largely ceremonial and tourist-focused, occasionally hosting special trains operated by Trenitalia for pilgrims and visitors, particularly those taking part in Vatican-organised excursions.

Happy Easter!

© Always Worth Saying 2025