“The record of what one man saw and heard and felt on a journey through Britain in October 1947, by John Alldridge”

Uncle John’s record of his trip round Britain, to assess the extent to which the nation was recovering a little more than two years after the end of the War, first appeared in the Manchester Evening News. Sadly, a few of his articles have been cut short as the original copies were corrupted in the archive process – Jerry F

Chapter 7 – The city that knows where it’s going

Coventry

I came into Coventry on a morning of hard frost and heavy mist. I was impatient for the curtain to rise and a bit apprehensive. For I had not been to Coventry since long before the war, and I hardly knew what to expect. I dreaded a repetition of Jarrow and elsewhere.

But I need not have worried. For the moment the mist lifted, like a safety-curtain going up, and the sun ripped through to spotlight the proud gold cock on the spire of the shattered cathedral I knew that down here in the Midlands I was a thousand miles away from the Jarrows of this world. After a diet of flat beer and skilly I was about to be served champagne and caviare.

“Stand fast in the Faith. Quit ye like men. Be strong,” said the blitzed church of Holy Trinity, in bold black letters a foot high. “Work in Progress. Keep Off,” growled the boards in Broadgate. Not once while I was in Coventry did I hear that horrible word “frustration.”

For Coventry, in spite of its scars, which are as red and raw as they were, I imagine, five years ago, offers you hope — something to live for, something to look forward to. An unending stream of traffic flows through the city, so that Broadgate, Coventry, is harder to cross at any time of day than Market Street, Manchester, is at midday. People move about briskly, as if they know where they were going and really wanted to get there.

I sat in the Town Clerk’s office and smoked a pipe with the Town Clerk, a vigorous young Yorkshireman. Like every other Town Clerk in every other bomb-damaged town, he is making a nuisance of himself with the Ministry of Works trying to get priority labour and material for his town. “There isn’t much we can do until Whitehall decides to lift restrictions,” he said. “So while we’re waiting we might as

well give people something to look at, no matter how small it is, to show that we haven’t forgotten.”

That is the difference between Coventry and some other towns and cities I’ve visited. In Coventry you are acutely aware that something is being done about it. Something to be going on with. Something you can see.

Scaffolding rises around Broadgate, the city’s main shopping centre. Neat little prefabricated shops seem to tap you on the shoulder and say, “Not much at present. But just you come back in a couple of years!”

I was not surprised to learn that the population of Coventry, which shrank to a mere 150,000 after the blitz of 1940, is now bigger than it was in pre-war years.

A large proportion of this labour force is employed in the huge motor car factories which ring the city. In these factories — long, low, attractive buildings, designed like Georgian manor houses, each in its own parkland — the work is monotonous but easy, wages are remarkably high, and conditions are palatial compared with the grim steel mills and obsolete workshops of the North.

I spent the rest of the day in the Standard Motor Works, which directly employs 10,000 men and women, all of whom are concerned in manufacturing 200 motor cars and as many tractors each working day.

I was taken round the huge assembly shop by a cheerful little Birmingham Irishman, bubbling over with aggressive enthusiasm, whose god, it seemed, was the efficiency of the internal combustion engine, and whose prophet was Sir John Black, managing director of Standards.

Vintage car at the Wirral Bus & Tram Show,

Rept0n1x – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

We stood and watched motor cars apparently building themselves at the rate of one every two and a half minutes, the slowly moving belts and a sort of overhead railway delivering bumpers and mud-guards and headlamps and buckets of nuts and bolts to where men were waiting for them. The belts never stopped. The men tightened nuts and sprayed paint at the same speed and with the same minimum of effort. To an imaginative mind it can be rather terrifying.

But there is no doubt that these men enjoy their work. (Last few paragraphs missing – Jerry F)

Chapter 8 – There’s chocolate in the air

Bournville

In a world of jarring crises it sounds odd to hear the problematical amount of chocolate which you and I would or could eat, if we had the chance, discussed with deadly seriousness. But here at Bournville, where the very air is saturated with the aroma of roasting chocolate, it is the one question everybody asks and seems afraid to answer.

I would not call Bournville — this vast co-operative organisation, with its schemes of social security that pre-date Beveridge, with its acres of playing fields and trim little ideal workers’ homes — a happy place just now.

By that I do not mean that there is anything domestically wrong with the factory or the way it is being run. The fraternal spirit of the two Quaker brothers who founded it still pervades the place. Of all the industrial plants I have visited so far Bournville has shown me cooperation between worker and manager at its best.

“Here at Bournville we reckon that a man joins us at 16 and stays till he’s sixty,” I was told. And to prove it they showed me a list of guests at the firm’s last Long Service Party in May. Of the 57 men and 14 women gathered together eight had 50 years’ service and the rest 40 years and over.

But you could not call it a happy place because for over a year now the whole organisation has had to watch the work of a generation practically shipwrecked. For years the goodwill of the business has been built up on what they call here “C.D.M.” — a two-ounce block of dairy milk chocolate. Before the war 26 million gallons of milk flowed into the factory every year and flowed out again as tablets of dairy milk chocolate.

Today almost all the milk collected on the firm’s four country milk factories goes instead to make cheese and butter and dried and condensed milk. They are making other types of chocolate here. But very little of it is the world-famous “C.D.M.”

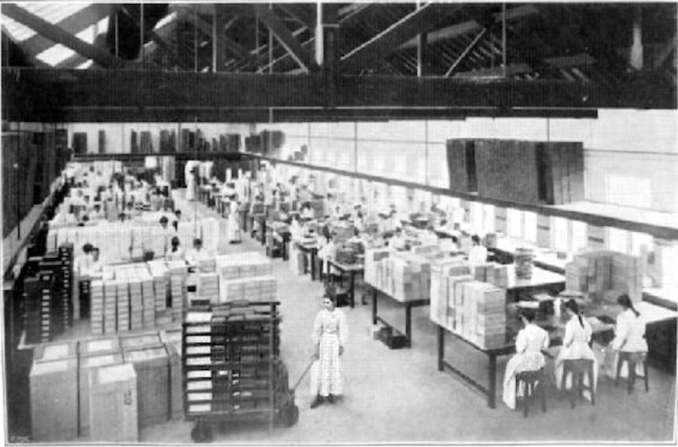

There was a time when a trip round Bournville was as inevitable as a visit to the Tower of London. The firm’s publicity department maintained a team of 150 guides solely for this purpose. But now visitors are not encouraged — there is now nothing that you couldn’t see in any factory working on mass-production lines.

The egg-cracking department, where you pressed your nose against the glass and watched hundreds of eggs being mechanically broken, is not functioning. Nor is the workroom where you used to be able to see nimble-fingered girls packing assorted chocolates into gay, ribboned boxes.

Packing room Bournville,

Unknown photographer – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The work going on here is just as prosaic as any I’ve seen in Sheffield or Newcastle. With one exception — here you notice a grim earnestness about it all — a sense of working against the clock. To catch up on production the already hard-worked machines are working night and day.

It’s ironic to think that a chocolate bar should arouse more enthusiasm in the man or woman engaged in making it than an ocean liner. But that is I have seen it. Perhaps this is this difference; not only are Cadbury’s workers among the firm’s best customers, they tell me they feel vitally concerned about everything that affects the firm.

This becomes understandable when it is explained to you that under the firm’s pension scheme it is possible for a man earning the average wage of £200 a year to retire at 60 on £140. With that to look forward to a man knows where he is going.

Looked at in that light it effectively reduces the huge chocolate factory, with its 10,000 workers to the proportions of the corner sweetshop.

Chapter 9 – A house for sale

Stratford-upon-Avon

A hundred years ago last month, a citizen of Stratford, one Thomas Court, offered for sale a “double tenement” in Henley Street.

The property in many ways was commonplace enough, comprising as it did a butcher’s shop and a small beer shop called “The Swan and Maiden Head.” But it was unique in this one respect; in one or other of the rooms above the butcher’s shop William Shakespeare was born.

Shakespeare’s house in Henley Street, Stratford-upon-Avon,

Edward Duncan – Public domain

They were still celebrating the centenary of its purchase as a national memorial when I arrived to pay my shilling and thus add one more to the 50,000 visitors who have already visited the birthplace this year. In honour of the event the house has had a coat of paint. And one downstairs room has been turned into a picture gallery.

But otherwise the place is much as it always was — an imposing monument to human credulity.

I gather that the Shakespeare industry is as flourishing as ever. True, there is an acute shortage of picture postcards and brass souvenirs. One or two of the younger guides are wondering whether they will be directed into industry now that the season is over.

Stratford folk don’t like you to talk about the “Shakespeare Industry.” They ask you to excuse all the olde-worlde teashops and art-and-crafty bazaars as the result of years of infiltration from outside. Modern Stratford earns a better living nowadays bottling fruit and vegetables in the nearby cannery, selling seed and fertiliser, and making biscuit tins and road signs in the art metal factory.

Even here in Stratford, the malaise of discontent showed itself the other day when for the first time in its history there was a strike at the town’s old-established family brewery. It was soon settled. But the thought that it had happened at all shocked the town.

It shows itself in saloon-bar conversations when men talk brazenly of black market butter at seven shillings a pound and eggs for the asking at sixpence each. And you hear of “quaint” cottages with four-and-a-half inch walls and no damp course prettied up to sell for £7,000 while just outside the town “squatter” families shiver in derelict army huts.

And at their last meeting the venerable society of Stratford Wranglers proposed “that England is still the best country in which to live” and carried the motion by an overwhelming majority.

Chapter 10 – Accent on youth

Cheltenham Spa

I always thought of Cheltenham as one vast United Services Club. I imagined it to be a coldly beautiful Regency town where ancient half-pay warriors in shabby tweeds could go pottering happily about, fighting their battles over again in between bouts of abusing the Government and reading “The Times” obituaries until death called them, too, on the Last Parade.

It may have been like that once. The tradition lingers on. It is commemorated in neat, soldierly boulevards with names like Vittoria Walk and Wolseley Terrace. Bearing silent witness to the military occupation that lasted more than a century are the “gentlemen’s shops” in the Promenade that offer hunting saddles and yellow waistcoats and pigskin-handled umbrellas at eight and a half guineas each.

But this, I am assured, is largely genteel camouflage. The military caste is fast disappearing from Cheltenham. It has been driven out by the rising cost of living.

The most difficult thing to find in Cheltenham is accommodation. The average residential hotel charges 10 guineas a week for full board (from what I saw of it the board is very full indeed). And in almost every case there is a long waiting list

A rough estimate shows that whereas the official population of Cheltenham is 50,000, there are more than 70,000 people living in the town today. Which is why, I suppose, I heard more complaints about food shortages in Cheltenham than in any town I have so far visited.

I walked around the town with a Cheltenham man, long resident in America, who returned towards the end of the war to find that a social revolution had taken place in his home town. As we passed the New Club (he called it, mock-serious, “the last death-rattle of reaction”), which may have been new when the Iron Duke was an honorary member but is now thickly draped with ivy, he chuckled.

“I can remember when that club turned down the heir to a tobacco fortune and a malted milk millionaire on the grounds that they were tradesmen,” he said. “But they’re not so particular today.”

And he told me how, during the war, the local Civil Defence system revolved around a middle-aged builder and decorator. He had a dozen retired colonels and major-generals running at his beck and call. Now he is back at his old trade, and the major-generals are proud to buy him a drink.

All this pleased my friend immensely. It was the sort of revolution he approved of. “I’d like to show you something else you’d never have seen here before the war,” he said. And he led me away into a block of Regency terraces to the town’s Civic Theatre.

We climbed up into the gallery and looked down on serious young women in black tights whose lower limbs seemed to be made of rubber, so easily were they able to touch their toes with the backs of their heads.

“Youth,” said my friend. “Something you never expected to find in Cheltenham, eh?” And he added, “If you were to ask me what was the town’s principal industry today, I should answer just that — youth.”

I knew he was not just thinking of the half-dozen famous schools and training colleges which have long been settled in and around the town. He was thinking more of this Civic Theatre. It was once a Victorian Turkish baths, but now seats an audience of three hundred in comfort.

This is an entirely spontaneous and wholly amateur enterprise, though it is sponsored and subsidised by the corporation. Each week throughout the year a different amateur dramatic group stages a play. On the rare evening when there is no performance there will be a session of the Gramophone Society or the Theatre Club, or a film show staged by the Film Society, with its membership already a thousand strong.

The week I was there they were doing a play by Jean-Paul Sartre. One could almost see the ghosts of those old Peninsular heroes boggling over the name and wondering what “Old Boney” would be up to next…

Reproduced with permission

© 2024 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2024