El Centro Histórico de San Salvador,

Lexdjelectronic2013 – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Puffins arriving at San Salvador’s Saint Oscar Arnulfo Romero International Airport crouching down to avoid the gunfire and running through the terminal building with their case over their head to deflect shattering glass may be overreacting.

Lying in a taxi footwell offering a bundle of notes to a startled driver (assumed to be a Mestizo with an eyepatch, gold teeth and a Virgin Mary tattoo across the back of his one remaining hand) might make one look a fool.

Pleading to race through rubble-strewn roads to a one-horse provincial town where a chap you remember from school’s aunty promised a guest room after an unexpected midnight call from a puzzled nephew might label you a bit 1980s.

For the long-running civil war that readers of a certain age will think is synonymous with El Salvador ended over three decades ago.

Raging from 1979 to 1992 the devastating conflict arose from longstanding social, economic and political grievances. The conflict pitted the government, backed by the military and conservative elites, against leftist guerrilla factions, primarily the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN).

The roots of the violence can be traced back to the early 20th century when a small ruling class held power and controlled much of the country’s wealth. The majority of the population, particularly rural peasants, lived in poverty and faced social and economic marginalization. Tensions escalated in the 1970s as various groups, including students, unions and peasant organizations began to demand political and financial reforms.

The national airport is named Saint Oscar Arnilfo Romero for a reason. The assassination of Archbishop Romero in 1980, a vocal critic of the government’s human rights abuses and injustices, catalyzed the eruption of widespread violence. The government’s repressive response to dissent, including the use of death squads, further fueled the discontent and led to the radicalization of many disaffected citizens.

The conflict intensified as the FMLN and other insurgent groups gained strength and carried out guerrilla warfare against the government forces. The war took a heavy toll on civilians, with widespread human rights abuses, including massacres, forced disappearances and torture, perpetrated by both sides. The United States, fearing the spread of communism in the region, provided significant military and financial support to the Salvadoran government.

Militares, en el marco de la ofensiva de 1989,

AlfredoMercurio-503 – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

International pressure mounted on the government to address its human rights abuses and engage in peace negotiations. In 1992, the Chapultepec Peace Accords were signed, bringing an end to the civil war. The accords included provisions for the demobilization of the FMLN, the restructuring of the military, and the establishment of truth and reconciliation commissions to address past atrocities. The civil war left a profound impact on El Salvador, resulting in an estimated 75,000 deaths and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people.

Then again, such a travelling Puffin a fool of themselves might not be making.

Following the war, deep-seated social and economic inequalities continued to challenge. The legacies of the conflict, including the search for justice, reparations for victims, and national reconciliation, still shaped the country’s political and social landscape. El Salvador continued to grapple with issues of crime, corruption, economic inequality and the rule of law.

Efforts were made to rebuild and transition to a more stable democracy. However, the country faced challenges such as gang violence, poverty and natural disasters, including earthquakes and hurricanes.

As we leave the Caribbean Sea and begin our descent towards the Salvadorean capital of San Salvador, one feels obliged towards the official advice given in the CIA Factbook. Perhaps not what to be seen reading on a Great Circle secret Going-Postal peace mission heading into Central America (to creep into the USA via an unexpected route), but here goes.

‘Is beset by one of the world’s highest homicide rates and pervasive criminal gangs,’ is never the best start to pre-assignment prep but, as we shall discover, not for the first time the CIA are playing catchup. Let’s start with some fact-based analysis which can be copied and pasted en bloc.

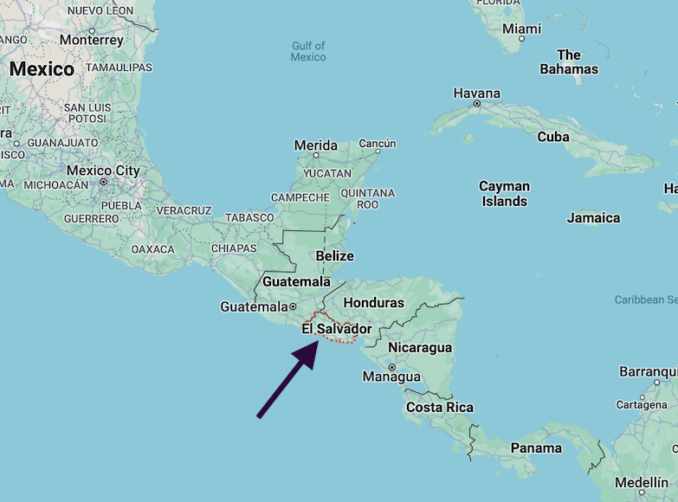

At 20,000 sq km and with a population of 6,000,000 our destination is the most crowded country in Central America and the only one without a Caribbean coastline. The area and population translate to a density of 307 people per square kilometre compared to 434 in overcrowded and immigration-blighted England. The countryside appears more sparse as 1.6 million live in the metropolitan area surrounding San Salvador.

© Google Maps 2024, Google licence

An additional 20% of Salvadorans live outside of the country as a result of civil war and economic emigration.

Those who remain – and one expects this will appear in the next edition of the CIA Factbook – live under a ‘state of exception’ adjudicated by the interesting President Nayib Bukele, the self-styled ‘world’s coolest dictator’.

Nayib was born into the Bukele textile, commerce, pharmaceuticals, advertising and media dynasty on July 24th 1981. After studying Law at the private Catholic university of UCA El Salvador, he developed a career in business before entering politics as the post-civil war peacetime FMLN mayor of the San Salvadorian suburb of Neuvo Custatlan.

Three years later, in 2015, he was elected mayor of San Salvador itself, again on an FMLN ticket. But within two years he had been expelled from the party for alleged ‘indiscipline and lack of respect.’

His tenure as mayor was marked by efforts to modernize the municipality and improve public services, earning him a reputation as a dynamic and innovative leader. Bukele gained attention for his use of social media to engage with the public and his focus on urban development and public safety initiatives. His popularity grew as he implemented visible changes, such as revitalizing public spaces and implementing programmes to address issues like crime and transportation.

In 2018, Bukele announced his candidacy for the presidency, running under the banner of the Grand Alliance for National Unity (GANA), a right-wing party. His campaign capitalized on his image as a non-traditional politician and his promises to combat corruption, improve security and stimulate economic growth.

In February 2019, Bukele won the presidential election in a landslide victory, securing over 53% of the vote and breaking the decades-long hold on power by the two major political parties, ARENA and the FMLN. His election marked a significant shift in El Salvador’s governmental landscape and reflected widespread dissatisfaction with the established elite.

Nayib Bukele and Gabriela de Bukele, 2019

Presidencia El Salvador – Public domain

After assuming the presidency, Bukele pursued an ambitious agenda, focusing on addressing issues such as corruption, gang violence and economic development. His administration implemented controversial measures, including deploying the military to combat gang violence and promoting infrastructure projects aimed at stimulating economic growth.

Bukele’s presidency is marked by a confrontational approach to opposition and a consolidation of power bypassing traditional institutions in pursuit of his policy objectives. His use of social media, including X/Twitter, is noteworthy, as he communicates directly with the public and often announces policy decisions through this platform.

This consolidation of power includes a ‘state of exception’ which gives the global human rights industry a fit of the vapours.

A recent Amnesty International report highlights permanent legal reforms approved under the implementation of apparent emergency powers which permits (what Amnesty describes as) an appearance of legality to the suspension of a series of rights and due process.

Principal changes include the concealment of the identity of judges, the automatic application of pretrial detention for crimes linked to gangs and the elimination of time limits for pretrial custody for misdemeanours associated with terrorist or illegal groups.

Various Civil Society groups allege 73,800 detentions, 327 cases of forced disappearances, an estimated 102,000 people imprisoned, a rate of prison overcrowding of 236% and more than 190 deaths in state custody.

What’s not to like?

As often, nobody’s happy except the voters. Eagle-eyed Puffins will have calculated Bukele to have been in office for five years. Brainy Puffins will already be aware parliamentary terms in El Salvador are also of five years. Sure enough, in a general election held last week (4th February 2024) President Bukele and his party were re-elected – this time with over 80% of the vote. Brainy Puffins pointing out that the constitution allows for only one presidential term are missing the point.

Perhaps most likely to vote Bukele are all the people who would otherwise have been murdered but are still alive. In 2015, 17 murders occurred per day. In the UK, with ten times the population, fewer than two. Another important demographic is young adults who for safety reasons had until recently only ever been outside of their houses in a taxi.

Bukele introduced the state of exception in March 2022 after a violent weekend claimed 87 lives. After that the murder rate has collapsed to the present one every other day.

A message here for British politicians regarding crime, punishment and popularity as we approach our own general election.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights,

CIDH Visita El Salvador – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Despite streets absent of vagrants or crime, Puffins are advised to take sensible precautions when visiting El Salvador and are further advised – given both the authorities’ zero-tolerance policy and the state of Salvadoran jails – to behave themselves!

Be especially careful to cover tattoos. Small town plod can’t be expected to know the difference between your first girlfriend’s nickname and the entire country’s gangland nomenclature.

Despite the attractions of the Geneva of Central America, we shall depart San Salvador as first planned and head for Aunty’s spare room out in the sticks. Next time, sightseeing a provincial gem in rural El Salvador.

To be continued…

© Always Worth Saying 2024