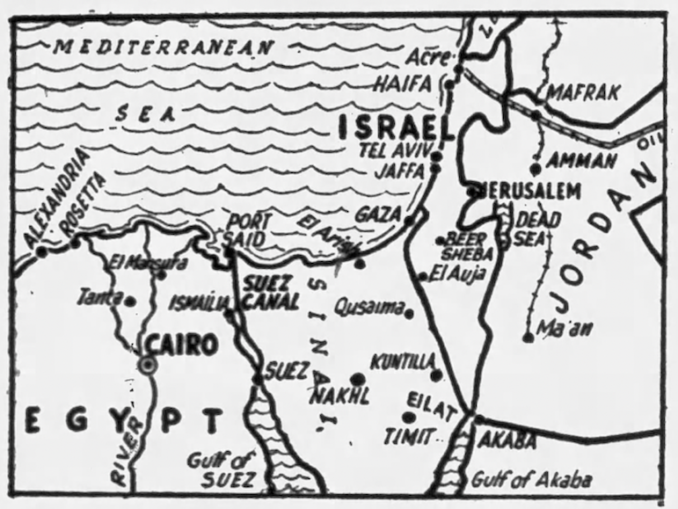

Israel,

Unknown artist – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

In 1957 my uncle, John Alldridge visited Israel for the Birmingham Mail. This is the third of his reports. – Jerry F

The first you see of it is a row of whitewashed oil drums, standing like guardsmen, shoulder to shoulder, blocking the road.

They are linked by a necklace of rusty wire from which dangles a yellow metal tag with the warning clearly marked in red: “Danger – Mines.”

Fifty feet further on is an identical roadblock. In between, in this deadly half-acre of no-man’s-land, barely hidden by the broken earth that covers it, is death itself.

Nothing has passed through that wire for three months. Nothing has moved, or flown, or crawled over this tranquil landscape for a hundred years you would say, so quiet it is.

Yet life goes on here. A kind of life. For this is the entrance to 125 square miles of the most disputed piece of land on the face of the earth. The Gaza Strip.

Where you stand, up against the wire, is Israel. Over there, on the other side of that ragged ditch, is Egypt. Shield your eyes against the glare and you can see the roof-tops of Gaza five miles away.

That sinister black hump on the skyline is Jebl Muntar. A perfect artillery post. In 1917 it held up Allenby’s Army for three weeks. Last November the Israelis took it in under half an hour.

Life goes on along the Strip. The wind ripples through the standing corn. High up, blessedly away from it all, a lark sings its heart out.

It is all so flat, so green, so peaceful it might be a bit of Lincolnshire.

About 50 yards beyond the wire on the Egyptian side an olive-drab tent is pitched beside the road. Above the tent flies a gay flag of Cambridge blue.

Now that your eyes are getting used to the glare, you can see spaced out across the fields other tents and other blue flags roughly 500 yards apart.

These are the forward positions of the United Nations Emergency Force. Their job is to keep anything from moving in or out of the Strip. But it would be easy to slip through that wide-open line in the dark…

Presently two soldiers in olive-drab uniforms and gay light-blue helmets come out of the tent and up to the wire to investigate you.

They are Indians, a sergeant and a private of the Indian Parachute Regiment.

You talk a bit. He tells you he is from Lucknow and served for six years with the British in India. He points to the Burma medal he wears.

But shouting across 50 feet of forbidden territory is tiring work. And so presently they salute and walk back to that stuffy little tent, two bored, lonely men, sick for home.

A mile away an Israeli picket faces a U.N.E.F. picket across a broken railway track. The same uniform, the same gay blue helmets. Danes this time. But take off the helmets, forget the flags that divide them, and you could not tell one from another.

They are all hot, bored, sick of a job which seems to have no beginning and no end. But the Israelis do have this in their favour… they are still standing firmly on their homeland.

So there is life of a sort on the Strip. And death, too.

While you are watching, a tractor comes grinding and lurching across the broken earth on the Israeli side; lurches close, perilously close, to that ditch. You see the driver has a rifle slung over his shoulder and a bandolier round his waist.

A few days ago one of those tractors ran over a mine. The driver was killed.

The next day an Indian patrol from U.N.E.F. went out to investigate, for this is supposed to be a demilitarised zone. They ran into more mines, and this time an Indian sapper was killed.

Nobody knows how those mines got there. No one appears to care…

I do not know what goes on inside the Strip, for without permission from the United Nations I cannot enter it. But I do know what is going on just outside it.

Spread out at regular intervals along the perimeter of the Strip on the Israeli side are 18 kibbutzim: communal settlements, made up of practical idealists, Jews from all nations, who live and work together for the common good.

One of these kibbutzim is more than 11 years old. Which means that most of them are just about as old as the Strip itself.

Born out of war, they were deliberately sited for their strategic value in just such an emergency as this.

They form, in fact, a chain of stout strongpoints, perfectly able to stand a siege of at least 24 hours.

And stand besieged for at least 24 hours they must. They cannot forget what happened in Israel’s war of liberation, when border settlements like these, overrun by an implacable enemy, were utterly destroyed.

So these border settlements, none of them more than a mile or two from the edge of the Strip, are tight little islands, manned by tough youngsters — girls as well as men — trained to use a rifle and a light machine gun in defence of their orange-groves, their precious water-supply, their very homes if need be.

Think of the early settlers in New England during the Indian wars and you have a rough idea of what life must be like in a border kibbutz anywhere along Israel’s 600 miles of troubled frontier.

I do not think Israel’s Press Office, by flooding the world’s Press with pictures of strapping young Amazons, armed to the teeth and ready for anything, is doing the female kibbutzik a service.

For most of them aren’t like that at all.

I was shown around Kibbutz Zekem, not by a muscular Amazon in battle dress, but by a pretty, very feminine, young woman called Miriam Szplro.

And by one of those strange coincidences that seem to happen all the time in Israel, Miriam used to live practically next door to me near Manchester.

I asked Miriam if she was ever homesick. A silly question, because, as she said, this is her home now.

But there are things from the past she misses sometimes. The rain. The Halle on Sunday nights.

Since that blitzkrieg campaign in Sinai last November things have been quiet along the Strip. Quiet by comparison, that is. They still go armed to work and take it in turns to do guard duties.

But apart from a few feet of precious irrigation piping stolen from time to time they haven’t been bothered lately. The oranges are growing, the date palms are growing, and everything in the garden is lovely… or seems to be.

But they daren’t relax for a moment…

Further down the Strip, where it swings in a sharp left-hook, is Ein Hashlosa, a kibbutz settled by Jews from South America. And at Ein Hashlosa they showed me one of the saddest things I have seen in a long, long time…

It is an air-raid shelter for babies. A cool, narrow, underground passageway lined with rough wooden bunks and tiny cribs like mangers, one above the other.

At one end is a cupboard of food, a small first-aid kit and a miniature kitchen.

Over each bed is the name of a child…

Reproduced with permission

© 2024 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2024