Another chapter from “Special Assignment” by my uncle John Alldridge

(published in 1960 and now long out of print)

When the first great war correspondent, William Howard Russell, went out to the Crimea for the Times, the army would have none of him. He had to pitch his tent outside the camp and live on what scraps he could pick up from the cookhouse.

Things were not much better in 1914 when the Daily Chronicle sent its star reporter, Philip Gibbs, to France.

The Army didn’t like journalists. They had an uncomfortable habit of finding out things that were better kept undercover. They asked too many questions; and during the Boer War, more than one unfortunate general had lost his command because he couldn’t find the right answers.

So when the British Expeditionary Force sailed for France in August 1914 Lord Kitchener, who was head of the War Office, refused to appoint any official war correspondents to go with it. One blood-thirsty old general threatened that, “If he caught one of those scribbler-fellers sniffing around his division he’d have the feller shot as a spy.”

This was taking the war straight into Fleet Street, for no journalist likes to be dictated to, whether by a pompous Town Clerk or by a brass-bound Commander-in-Chief.

So a few adventurous spirits decided to go out to France as freelances – without permission from the War Office, but with their editors’ full approval.

One of them was a young reporter called Gibbs.

If he couldn’t travel to France with the Army he could still go as a civilian, he reasoned. For the normal cross-Channel services were still running.

‘After a short time in Paris I set out for the Front with a wad of writing-paper, several tins of cigarettes and 200 golden sovereigns in a belt underneath my waistcoat,’ he remembers.

‘I linked up with two friends from Fleet Street. One was Massey of The Daily Telegraph, and the other Tomlinson of The Daily News.

‘Strange as it may seem, a few French trains were still running quite close to the advancing Germans, and my friends and I boarded one of them going to the famous old town of Beauvais. We were the only passengers; and when we drew near the town we saw a number of French machine-gunners lying behind an embankment and looking as though they expected the enemy at any moment. They did!

‘When we got out at Beauvais we found that all the inhabitants had fled except, apparently, the Station Master and ticket collector. They were frightened men, and told us the situation was very bad. There was a great German army on the hills above the town and they expected to be killed or taken prisoner within an hour or two. “You’re just in time to join us,” added the Station Master, grimly.

‘It wasn’t a pleasant outlook. But I suggested that the little train which had just brought us in could take us out again.

“They may have cut the line farther down,” warned the Station Master. But we took a chance; and that night we drove out between two fires, with the French guns booming on one side and the German guns blazing away on the other.

‘It was a near thing. But we made it. And so we were in time to see the first arrival of the British Expeditionary Force – afterwards to be called “The Old Contemptibles”, because the German Kaiser had spoken of them as “that contemptible little army”.

‘They were very young men, then. And as smart as new brass buttons when they arrived, laughing at the French girls who threw flowers and kisses at them. That was before their fighting retreat from Mons, when they were unshaven, dirty, plastered up to the eyes with white dust.

‘My friends and I had to return to England for a few days. But once in Fleet Street we were in a hurry to get back to the war. By bad luck I missed the train from Victoria to Dover by ten seconds. To the dismay of my friends, who were leaning out of the carriage window and saw the gates slammed against me. It was then that I used some of those golden sovereigns tucked away in that belt under my waistcoat.

“How long would it take to get a special train?” I asked the Station Master, who was standing by.

“Just as long as it would take you to pay the money, he told me. It took me three minutes; and I found a special train waiting for me. It had three coaches, an engine driver and a guard. I arrived at Dover just a minute behind the train I had failed to catch. And when my friends saw me walking down the platform they thought it must be my ghost!

‘After that I separated from them and in order to see the war in Belgium, I became a volunteer stretcher-bearer with an ambulance unit working close to the fighting line. Here, day after day, I saw at close quarters the flame and fury of war.

‘By this time I was in very black books at the War Office because of all my “unauthorised” articles which had been published fully in my newspaper. By Lord Kitchener’s personal order I was down for arrest at any port in France. Unaware of this I went to Le Havre where I was arrested by three Scotland Yard men.

“You’re wanted by General Bruce-Williams,” they told me sternly. “He’s been looking for you for quite a time.”

General Bruce-Williams was very hot-tempered indeed. He threatened to have me shot against a white wall. Instead, I was kept under close arrest. But somehow I managed to smuggle a letter to the editor of the Daily Chronicle who got busy on my behalf. I was set free. And not long afterwards, to my astonishment, I was appointed one of the five official war correspondents on the Western Front. Lord Kitchener had forgiven me. . .

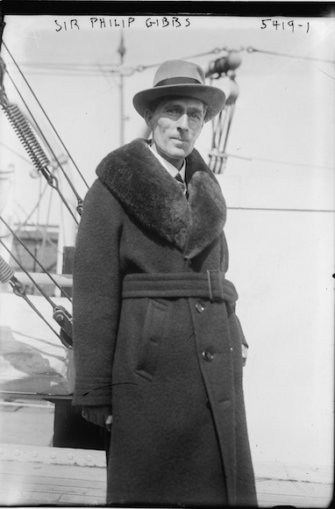

So instead of being shot as a spy, young Gibbs went on to become one of the great war correspondents. He saw that terrible war through the eyes of the men who were fighting it. And so revealing were his despatches to the people at home – who often had only the vaguest idea of what was going on – that after the war he was knighted for his services in the field.

And as Sir Philip Gibbs he is still one of our best-selling novelists.

Sir Philip Gibbs,

Bain News Service – No known copyright restrictions

By World War II the war correspondent was well-established. He wore a uniform now and carried the honorary rank of captain. He lived in a Press Camp, with Public Relation Officers at his beck and call. And Field Censors to drive him frantic sometimes.

His free-lancing days were over. He was officially ‘accredited’ to an army: and sternly forbidden to move out of that area. But unlike the old-time freelance, he lived with the fighting men and went into action with them. Armed not with a gun but a typewriter. As a result, the reporter and the soldier had learned a new respect for each other.

To the Army, war correspondents were no longer meddlesome civilians in a kind of khaki fancy-dress; they knew the Army jargon and the Army ways. They were men of the Army who happened to have an unusual but specialised job.

And they had the confidence of the High Command. Before a battle was fought they would be invited to a top-level briefing and told exactly what was expected to happen. Never once was that confidence abused for the sake of an ‘exclusive’ headline.

World War II produced many fine war reporters. Men who obeyed the rules but went their own way.

One such was Alan Moorehead, the brilliant Australian newsman who followed the war for the Daily Express from El Alamein to the final victory.

I met Moorehead many times at press conferences. He was the beau ideal of war correspondents. Darkly handsome, always impeccably dressed, his Eighth Army desert scarf tucked nattily-negligent in the top of his battle dress, Moorehead always looked to me as if he had stepped straight out of the bath and was on his way round to the club.

Alan Moorehead,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Yet Alan Moorehead had come closer to war than many professional soldiers.

In June 1944, he was one of sixty correspondents officially accredited to the Liberation forces about to invade Europe. As always, he went in with the first assault wave. And as always, the dispatches he sent back were vivid word pictures of that epic moment, framed in the sort of language everybody could understand.

‘At nine o’clock the captain shouted down from the bridge,’ he remembered later in his book, Eclipse.

‘He had a signal form in his hand, but I could not hear what he was saying and I clambered up to him. “Two companies ashore and reached their first objectives with only slight enemy resistance”.

‘It was scrawled in pencil on a pink slip of paper. One was not able to comprehend it. We stood in the wind looking at the paper, re-reading the scrawling handwriting. One had nothing but a sense of confused anti-climax. This signal bore no relation whatever to the long, hard expectation of this day. It was almost an impudent comment on all the dread of the past week. It punctured all the unending imaginings, all the lurid apprehensions. The tremendous shelling and the sunken ships. The men drowning in the water and crawling bleeding on the beach. Where was it all? There was nothing around us but the grey sea and the peaceful passage of other ships, nothing to illustrate this perfunctory message that had come from somewhere out ahead, from someone actually standing on the French shore, someone who had made the landing and lived.

‘And then when we finally came up to the invasion beach and stared across the water there was a second and deeper anti-climax. There it was. France after five years. It was incredibly and inexplicably the same. A stretch of sea-shore. The ugly little seaside villas. The lovely gentle slopes behind running into green copses and straggling farmyards. A windmill on a hill. Yellow cliffs on the right. No rolling battle clouds. No diving bombers. No noise like the monstrous noise one had imagined. All one’s memory of France rushed up to meet this positive visual proof that it was the same. Yes, of course.

‘This was the place to which one took the children for the summer holidays. There should be coloured parasols down there on the plage, an ice-cream man on the promenade. “Demandez de la glace. Un franc la coupe”. Governesses. Little Frenchmen with spiky beards and straw boaters. Baskets of crayfish. The pension on the hill.

‘Nothing in all one’s experience could have been a preparation for this picture postcard, this unbelievable quietude; a French beach by the sea. This was the focus of the world, the cataclysm behind the headlines and the urgent radio bulletin. And look at it: a French beach on a summer morning. As we looked and looked a tremendous tide of relief came into the mind, as though we had suddenly woken after a long fever with a normal temperature, and all the pain had drained away.

‘Yet there was a battle going on. As we crept closer one could pick up the detail. In the six hours since dawn, something like a thousand ships had arrived on this stretch of beach. Cruisers and battleships were standing offshore and firing on the heights above the cliffs, presumably against the unseen German batteries. Perhaps a hundred of the larger landing-ships were rolling in the waves a few hundred yards off-shore, vainly trying to unload their tanks and vehicles on the Rhino Ferries [see Note 1 below]. Each time the ferries came up to the open mouths of the ships they were dashed back by the waves and drifted away. Those “ducks” [DUKW – see Note 2 below] which had been got into the water were either struggling towards the shore or swamping and sinking outright with their crews on board.

British Forces during the Invasion of Normandy,

No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Midgley (Sgt) – Public domain

‘The tide had already receded, and upon the shore itself many landing-barges were beached or awash and rapidly sinking into the sand. Four or five ships were alight and burning brightly, throwing out shells and explosives over the debris at the water’s edge. German shells were falling in little puffs of grey smoke, but the whole scene looked at from this distance was toy-like and unreal. It lacked the element of danger or excitement, even of movement. Behind us more and more ships were coasting in, until the whole horizon towards England was blocked by a jagged line of tossing silhouettes. Occasional aircraft flew by, but aimlessly and apparently without obvious direction. We put out a motorboat from our landing-ship and it filled and sank. Our ferry arrived and shot upward past the open bows like a huge electric lift. As it subsided it slewed around and drifted away. All the rest of the day passed like this. The ferry smashing up against the side of the ship and drifting away; the curious toy-like scene on the beach, the battle without explanation and without movement. It was agonising not to get ashore, only 500 yards away. There was nothing to do but stay in the unreal and unwanted calm of the American ship, taking hot baths, eating grilled steak, listening to the infuriating swing music through the loudspeakers.

‘In the morning nothing had been changed very much except that there were more ships in the sea, more wreckage on the beach, more fires burning inland. A few of us managed to drop onto the ferry, and like a bull running amok it ran for the shore on the incoming tide.

‘We smashed against the next ship and wrecked a longboat. Then the ungainly thing, with only one engine working, veered in the opposite direction and smashed its dead weight through a shoal of ammunition barges. All about us ducks were sinking and soldiers splashing about in the water. Our actual landfall was perfect. The ferry, long since out of control, lunged up against a wreck at the water’s edge, and we jumped for the shore. A 6-foot soldier for no reason except generosity, yanked me on top of his shoulders and set me down on the dry sand with my typewriter dry and intact.

‘The beach was an extraordinary shambles. So much had happened in the past twenty-four hours; wreckage piled on wreckage, that one had the impression that the battle had been going on for a long time, for weeks, even for months, and that the soldiers who came to meet us on the shore were natives of the place.

‘At the spot where we landed two Sherman tanks had already sunk up to the turrets in the quicksands. A sharp wind was blowing over the sand dunes and now that one was close at hand one saw that this was no normal French beach but a wasteland pitted with thousands of craters and shell holes. The villas were only shells, with their insides blown out. The roofs of the farmhouses had tumbled in. The pillboxes and concrete trenches had been wrenched about by the fantastic violence of the barrage of the day before.

‘The first companies onshore had found the enemy broken and dazed by the bombardment but there had been bitter skirmishing, and the dead lay about the blackened entrances of the pillboxes. A stream of ducks was making directly up the hill to the village of Crepon. Following them one travelled quickly through the belt of utter destruction on the seashore and came out into the clean countryside beyond.

‘In a wheat field a platoon of German soldiers had held out for a little. They lay dead now in the positions in which they had been firing. But then beyond this no sign of the enemy anywhere, not even the sound of continuous firing. There were other experiences in other sectors, harder fighting. The parachutists, for example, were under continuous fire on the Orne canal and the Americans to our right were engaged in a pitched battle on the beach. But here, after the first assault, it was a clean break-through. A breach had been driven clear through the Atlantic Wall, and bewildered German soldiers were running for cover through the open countryside.’

There may have been more dramatic accounts of D-Day than this. But none, I feel, which expresses more exactly that unreal, dreamlike feeling that comes on a man when he looks at a landscape over which the tide of war has just rolled.

This was no future historian writing for posterity.

This was one man watching history as it happened through the eyes of the hundred thousand men who made it.

And that is the essence of great reporting.

Notes (courtesy of Wikipedia):

1 A rhino ferry is a barge constructed from several pontoons which are connected and equipped with outboard engines, used to transport heavy equipment and people. Rhino ferries were used extensively during the Normandy landings

2 A DUKW is an amphibious transport vehicle.

The name DUKW comes from General Motors Corporation model nomenclature:

D, 1942 production series

U, Utility

K, front-wheel drive

W, tandem rear axles, both driven

DUKW on a road during World War II. ,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Jerry F 2022