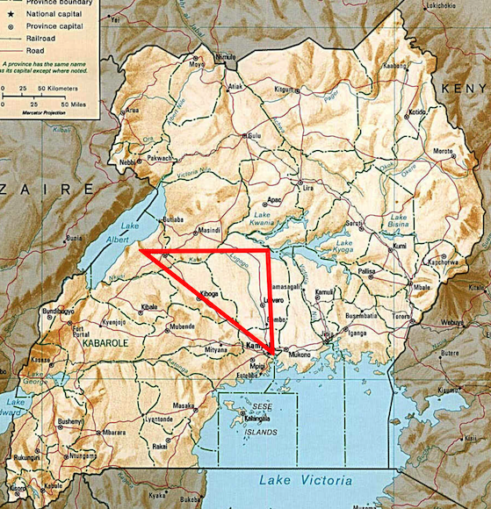

Luwero Triangle, a 2,800 square mile cheese slice of land NNW of Kampala.

Uganda large map,

United States Government – Public domain

Within it are 33 memorials scattered across the Luwero Triangle.

Some 4,000 lie buried in Kikyusa. They and all other memorial sites bear the witness the price locals paid for M7’s decision to use the area as the operational base for his campaign to overthrow Obote. A plaque declares the monument is in memory of “freedom fighters of NRM/NRA who died during the war 1981-1986. It’s an ambiguous formulation of words, as the vast majority, everyone acknowledges, were civilians. By dint of dying, they apparently took sides. Luwero’s thick tree cover and meandering papyrus swamps meant the area could effortlessly hide/swallow up men, vehicles and arms. With fertile soil, food was abundant.

President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda,

The White House – Public domain

M7 chose his operating base in Luwero for the majority of his campaign because of its proximity to Kampala, laying 15-20 miles north of Kampala. Kampala, the hub was also key in it’s where the nation’s key highways converged and the railway terminated. M7’s frontline camp, dubbed “Black Bomber Command” coordinated the Bush War. Being close to Kampala even allowed wounded guerrillas to be smuggled into Mulago Hospital for treatment by sympathetic nurses and doctors.

Obote’s one advantage was control of the airspace. However, with the thick tree cover in the hardwood forests, villagers easily avoided army checkpoints taking hidden fighters cassava, jackfruit, bananas. The villagers also ferried another hugely important commodity, information. In Kikyusa, it was gratefully received by a bespectacled, young man, Paul Kagame, learning the basics of undercover work. NRA knew better than to put its brains at risk, as fighting was never one of Kagame’s prime duties, he spent three years in the area serving as intelligence officer.

The NRA’s first attack on Kabamba barracks on 6th February 1981, the raid -involving the legendary 27 guns – featured a tarpaulin truck full of hidden guerrillas. At the barracks entrance, while the gate guard spoke with the driver, a Peugeot 304, with M7 aboard, came out from behind the lorry and the gunfight began.

The operation which Fred Rwigyema, Kagame and M7’s younger brother Salim Saleh took part, proved disappointing, capturing 16 rifles, 1 RPG and 8 vehicles. M7’s group was overwhelmingly a movement of southerners and westerners, aside the Banyarwanda, from regions that hated Obote for dismantling their kingdoms, and the brutality of his soldiers, almost exclusively from the north.

NRA fighters, back in the bush, noticed how M7 made a personal effort to connect with each new arrival, teasing out family connections and explaining the movements aims and M.O.

M7, as he’d learnt in Tanzania and Mozambique, drilled into new arrivals a good soldier is more than a man with a gun, he must grasp the purpose of the “struggle”. As a result, a political commissar was appointed to each NRA unit, and classes in politics, economics and history held in the bush.

Ultimate decision-making rested with an inner clique of Banyankole and Banyarwanda fighters, who were either related to M7, had grown up with him, or had been part of the original group that went with M7 to Tanzania and Mozambique. M7’s younger brother Salim Saleh and Fred Rwigyema were part of this inner core.

M7’s main lesson was: never alienate the support of the local population on whom “you” depend. So: no raping, looting, drunkenness, or requisitioning. Pay for food with cash, robbing banks if necessary and if NRA fighters misbehave, extreme punishment. Guerrillas deemed to have crossed the line were executed, in public, to show local villagers how serious NRA were to the issue of discipline. In this context, again Kagame pops up.

Kagame’s disruptive phase behind him due to the NRA giving him structure and focus, and his friendship with Fred ensured he was treated seriously by comrades. M7 spotting the same qualities Kagame displayed in school [aloof etc.] assigned Kagame to work under Jim Muhwezi. Muhwezi, a law graduate, famous for disguising himself as a woman to escape to the bush. Muhwezi drew on his experience working for Uganda’s police force in his role running NRA military intelligence.

As NRA’s footprint expanded, so did the area which Kagame roamed. He was sent extreme distances, on foot searching for contacts or places for forces to hide.

He’d study territory as to whether there was sufficient water, food, terrain to hide and whether the local population would provide support.

The Rise of Pilato

H.E. President of Rwanda, Paul Kagame,

ITU/J.Ohle – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Monitoring enemy activities was not the only focus for the NRA military intelligence. The primary task, as outlined by Muhwezi, was checking for subversion and infiltration into the NRM/NRA. Kagame’s job – monitoring his fellow fighters, would not have been to everyone’s liking, but it perfectly suited his personality. In keeping himself at arm’s length from other fighters, fighters came to feel Kagame was constantly totting up perceived failures in some personal Book of Judgement. Over time, as a result, there was a perception among fighters (and fellow officers) he was the “enforcer, or punisher” and was common knowledge throughout the NRM/NRA.

Whenever a disobedient guerilla came up for court marshal, it was Kagame’s job to make the case for the prosecution, revealing what he discovered during the course of investigations to a disciplinary committee. Kagame requested the death sentence with such alacrity that he acquired the nickname that dogs him to this day: “Pilato”.

Contemporaries marvelled at the triviality deemed to merit capital punishment. If two fighters were talking and a third joined them and the first two fell silent, that alone was considered reason enough that a plot was being hatched, with the first two might end up being sentenced to death.

Other crimes considered serious enough to merit execution included, but not limited to, internal rivalry, indiscipline, sneaking off for a beer, making noise, or dropping something when on patrol, leaving comrades during an ambush, Kagame wouldn’t hesitate to send forces to their graves. While not personally administering the death penalty, he rapidly gained the reputation that he enjoyed the role too much. Bitterness over why and how certain NRA fighters, regarded by the comrades as inspirational and honest, singled out for the death penalty, still resonates today.

As news, finally reached the public domain of the Kabamba raid spread, more recruits materialised. The following months were spent consolidating a clandestine movement that had attracted 200 men. This allowed M7 to split the sole force into six units deployed across the wider Luwero triangle’s five districts, laying ambushes, attacking police posts and administrative centres.

An April attack, led by Fred, on a government detachment based at Kikiri, 17 miles NW of Kampala, resulted in a generous haul of guns, mortars and munitions, that the invading force struggled to haul the gains away. M7 was still hungry for more weapons, so with six companions, crossed the front line, boarded a boat, and overnight crossed Lake Victoria to Kisumu in Kenya, then drove to Nairobi. Having signed a deal with the head of the Baganda militia, flew to Libya to meet with Gaddafi to make good on a promised arms drop.

Inside the Luwero Triangle, the NRM set up resistance councils staffed by peasants, precursors of the local councils on which M7 would eventually base Uganda’s National Administration.

With NRA gaining strength and support, in June 1982, Uganda Army’s Chief of Staff Maj Gen David Oyite-Ojok, launched the first major government offensive – Operation Bonanza. It was at this point Obote set his sights on the Banyarwanda community which was supplying M7 with so many of his fighters. The ethnic cleansing programme he set in motion eliminated any distinctions between Ugandan Banyarwanda and refugees. Anyone speaking Banyarwanda was designated “foreign”.

If Obote’s campaign was intended to deter community members from joining M7, it dramatically backfired. Rather than smothering resistance, it whipped it up. Now allotted pariah status in Uganda society, Tutsi youngsters knew a quiet life was ruled out. Enlistment to NRA soared. Once Ugandan administrators, UNHCR and WFP workers had left refugee camps for the night, clandestine meetings began. The ensuing days, teachers noticed class sizes were reducing.

In late 1982, Operation Bonanza began to bite and NRA’s stocks ran low. While an estimated 1 million civilians were now inside NRA-controlled territory, after two years of insurgency, the 1,500-strong NRA still owned only 400 guns.

May 1983 saw a mass exodus of civilians as famine in Luwero Triangle began to set in. Obote forces shelled bedraggled columns of villagers all the way. In government-held areas, civilians were “screened” by the army, a death sentence for many, the aim being to drain the NRA of any support.

However, NRA numbers continued to increase, but the government’s counterinsurgency campaign was gaining traction too. With NRA on the back foot, its luck changed as NRA shot down a helicopter carrying Maj Gen Oyite-Ojok. Internally in Kampala, internal battles for succession began immediately, taking the obligatory ethnic form, the army cancelled its ground offensive.

In February 1984, NRA’s confidence was high, and attacked barracks at Masindi, on the road to Murchison Falls, hitting the base when soldiers were hung over from a party. The NRA’s weapons tally was a thousand submachine guns and fourteen trucks’ worth of other arms and marked the turning point in the war. William Pike, the first Western reporter to visit the NRA in the field later in the year, confirmed the Luwero Triangle was firmly under NRA control. He also noticed the silence, the vast majority of residents either left or were dead.

Uganda in mid-1980s was a dangerous place for NGOs, human rights and journalists to operate. During the daytime, officials from ICRC, not usually easy to rattle, would drive into the Luwero Triangle visiting the 36 internment camps set up by Obote. At night – the potential witnesses were careful to be back in Kampala (also wracked by gunfire and the prowls of the Computermen) – the majority of torture, extra-judicial killings took place.

Obote countered claiming that yes, villagers were being slaughtered but not by his troops, this was NRA, donning government forces’ uniforms. NRA’s brutality was part of a “false flag” operation. It was an explanation, foreign embassies and the World Bank, whose “aid”, propped up Obote’s government, were ready to accept. Since Obote, the British Government, in particular felt, had brought an end to the clown Amin, his administration deserved support, rather than criticism.

In August 1984, the Western complicit silence was finally shattered.

In Congressional hearings in Washington and interviews with US MSM Elliot Abrahams, the US Assistant Sec of State for human rights claimed 100,000 to 200,000 civilians had died in the previous three years in the Luwero Triangle, either shot, shelled, starved or tortured in illegal detention/internment camps[1].

The British Government, leaping to Obote’s defence, countered with and estimate of 15,000 dead, which Obote would later blame on ill-disciplined troops, accidental deaths in “cross-fire” and bandits posing as soldiers[2].

But, days later, Britain’s Observer splashed William Pike’s account of his trip into the bush across its front page, an article which forever changed the way the “international community” viewed the Obote regime. He had seen first-hand the bodies dumped in shallow trenches inside abandoned ICRC camps, sprawled across rooms or left in the open to rot[3].

Another issue that continues to resurface during the bush war, involves the kafuni, a short-handled hoe used to dig holes and loosen soil. Part of any Ugandan farmer’s standard tool kit, it became associated with a method of execution by the NRA to despatch suspected informants.

In theory, one of NRA’s central tenets was accountability, and when “justice” was dispensed in rebel-held territory, the process was open, hence the testimony collected by mil intel officers (Kagame) and the sentence carried out in public. Kafuni was often used dispensing with Obote’s youth squads, villagers suspected of collaboration, or those who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, the bodies quickly buried in shallow graves in the forest.

Among NRA fighters, it was common that Kagame was closely associated with such operations. Being a rigid disciplinarian, the “Pilato” nickname was not solely rooted in evidence collection, but extended, what human rights organisations regard as extrajudicial execution. The same process applied to NRA fighters who became too ill to fight, visited the “sick bay” or those who decided “rebel life” wasn’t for them. Kafuni method usage was used during the latter Rwanda invasion and thereafter into Zaire.

Footnotes

[1]Ugandans charge US is seeking to undermine their government.

[2]Notes on concealment of genocide in Uganda.

[3]UK’s Observer ran “The Killing Fields of Kapeka” by William Pike, on its front page on 19th August 1984. Syndicated abroad, it was also a front-page story in France’s Liberation a few days later.

© AW Kamau 2023