Death has become too commonplace to matter. The two greatest products in Mogadishu are shooting and rumours: from morning to night, they manufacture rumours, from night to morning they manufacture shootings – Mohamoud Afrah.

Mogadishu: A Hell on Earth

In biblical times, the three wise men came from a land of Punt with their gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Such luxuries still grace Somalia’s markets, but post the fall of Siad Barre, weapons had been in much greater demand than perfume. Gold, such as that taken from the Italian bishop’s teeth, was of value only for the protection it could buy.

Mogadishu’s arms markets had grown unchecked since the eve of Barre’s collapse, when merchants quietly took clients aside to inspect clandestine weapons stocks. The markets teemed with criminals and self-appointed defenders and exited youth, testimony to an all-pervasive gun culture fed by Italians, Soviet and American “friends”. The markets contained the majority of Barre’s arsenal with enough firepower to repel an invasion, and that is exactly what it would be used for in 1993, to force American “peacekeeping” troops to go home.

Somalia was in enough trouble already, without Americans or anybody else. The capital was divided between the strongest clans, the Habr Gedir and Abgal, which had fought together to oust Barre. But then they squabbled over the spoils: who would be President? Similar to Beruit, Nicosia, Mogadishu was split between north and south by an unruly no man’s land called the Green Line. It was there that the gun market “merchandise” operated, it was at the gun market that gunmen congregated to discuss prevalent issues of the day. There was no law, no government. The gunmen were it.

Arms were, and still are, Somalia’s most useful currency. Along with food, they ensure the chance of living to tomorrow. Without a weapon, food would be stolen; but well-armed food could always be stolen. At the time, an Ak-47 cost US$70 and two full magazines cost less than a plate of goat meat.

Barren Somalia, already under the grip of militiamen with guns, disintegrated further. The defiling of the Italian bishop was the beginning, the prologue of violations that from 1991 would devastate the capital with the bloodiest civil war in Somalia’s history. The rival warlord’s quest for power, and the destruction wrought by Barre’s own defeated clansmen, would lead to famine.

Gangs of bandits looted and foraged, exacting a heavy toll. By late 1991 there were around 40 distinct bandit groups in Mogadishu alone. Hands soiled with dirt, they dug up every length of copper and phone wire under Mogadishu’s streets. Transformers were cut from poles to get at the half-pint of poor-quality oil inside. Whole factories were dismantled and sold, complete, to Arab countries by emerging “godfathers”.

“Chaos” would be an inaccurate word describing the looting. At the top of the informal clan power structure were former guerilla leaders and opponents of Barre who had removed him. Their claims to power and willingness to impose those claims by force, turned their titles to “Warlord.”

One of Barre’s worst legacies was his power addiction. The dark culture of his regime was injected into the minds of every Somali, the appetite for power, either for the individual or for the clan. Power in Somalia was synonymous with wealth, freedom and personal security.

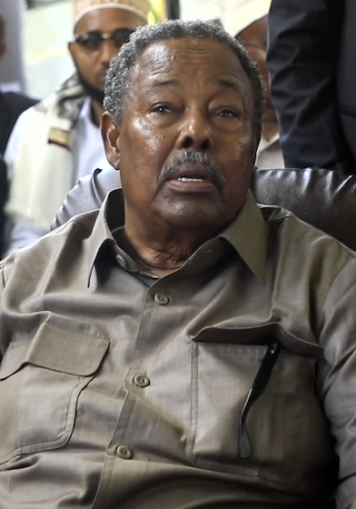

Aidid

Сомали Мохамеда Фараха Айдида,

Administration of Aidid – Public domain

The epitome of that power and use of it was General Mohamed Farah Aidid (pronounced I-deed), by Somali definition, warlord par excellence. Aidid was strong with a military sense of purpose and decisiveness. Aidid originally took over from Barre as chief of police in 1958, and during local elections held, had the hands of voters stamped to prevent them from voting twice. The rank of general was a holdover from his time in Barre’s army.

In the 1970s, Barre became aware of Aidid’s own coup plotting against him and locked him up for seven years. Aidid was “rehabilitated” in the 1980s when sent to India as ambassador. Then his Habr Gedir clan called him back to Ethiopia to serve as their “father of war” to head the armed rebel movement fighting together with Ethiopian military against Barre.

Aidid had the best claim to power: he’d toppled Barre and had popular support well beyond his own clan. As his clansmen had “inherited” a sizeable majority of Barre’s arsenal, Aidid first had to prove himself as the undisputed leader of Somalia.

Сомали Али Махди Мохамед,

Shabelle TV – Public domain

Aidid directed his Habr Gedir subclan to wage war against the rival Abgal subclan, led by Ali Mahdi Mohamed, a nondescript hotelier who had appointed himself president. During the removal of Barre, Aidid and Ali Mahdi had been allies, both leaders of the United Somali Congress and the larger Hawiye clan. The split was caused by mutual provocation, mutual intransigence and mutual thirst for power. When Barre fled, Ali Mahdi had declared himself head of a new government so rapidly, that his chosen future “Ministers” hadn’t been notified. Aidid, whose forces had conducted most of the battles against Barre, was livid. As head of the more aggressive Habr Gedir, he attacked later in 1991 to claim the top slot for himself. Given he had more firepower, he was able to back his argument with force.

The traditional Somali custom/system that once bound clans to preserve peace, or at least stem war, collapsed with clouds of cordite. The power conflict divided Ali Mahdi’s northern Mogadishu enclave from Aidid’s turf in the south, therein creating the green line. Within days, with killings so widespread, nothing short of destroying the enemy subclan would end the blood feud.

Most of Mogadishu’s population was Ali Mahdi’s Abgal subclan, but Aidid had heavier weapons, controlled the bigger swath, and was reinforced with peasants from rural areas. The General won major battles, only to lose the same territory overnight as Ali Mahdi’s “infantry” reclaimed lost ground. The constant seesaw reduced the centre of Mogadishu to a wasteland.

A long shot of an abandoned Mogadishu street known as the “Green Line”,

Ph1 R. Oeiez – Public domain

But waging war, even in Somalia, couldn’t be done alone. Aidid relied on a close relation with a financier. Osman Hassan Ali “Ato” was one of the godfathers, a self-made businessman, master of the Hawala money remittance system, with a large personal militia and significant interest in Somalia’s lucrative qat trade. Ato controlled the daily inbound flights of Qat with his own small fleet of planes from Kenya, a business valued back then at US$1 million per month.

Ato had a decent living, even at the time in Somalia, but played the game of survival by the same unwritten rules of those on the streets. Like every Somali, he said he wanted peace, but hedged his bets with a network of 6-8 garages that converted stolen four-wheel drive Toyota land cruisers into battle wagons. Gunmen were paid US$150 bounty for every vehicle looted that could be transformed. There were also 20 similar garages across Mogadishu, and there were other godfathers. Ato was a man who knew very well the bottom line and foresaw a long clan war in Somalia, so he prepared the war machinery. His operation was well-controlled.

He regularly went to Ethiopia for regular shopping sprees, filling gaps in Somalia’s arsenal with the for-sale remains of Ethiopia’s fallen Marxist government. He supplied qat to pay clan militias. His garages were where the real engines of war were primed, removing Land Cruiser canopies fitted with custom-made mounts bolted to the chassis, fitted with American 106mm anti-tank cannon, Chinese recoilless rifles or Soviet anti-aircraft batteries adjusted horizontally for street battle. In Somalia they were known as “Technicals”.

Such highly mobile firepower was first used to great effect in the 1980s in Chad’s northern Tibesti Mountains by President Hissein Habre against Libya-backed rebels.

The lesson of their success was not lost on Somalis whose battles in the interior and sandy city alleyways required mobile force. In Barre’s final days, Big Mouth had also created a small, similar fleet to quell unrest, in vain. With Barre gone, gunmen operating the Technicals turned Mogadishu into a “Mad Max” post-apocalypse scenario.

Aidid knew without this support, his claim to power would sound hollow. The warlords simply extended traditional clashes among nomads over grazing and water rights to a more destructive level. Mounting deaths were not the only degradations. Traditional warrior codes dictated that women, who along with children, are deemed to be among the “weak” and never to be harmed. This was violated repeatedly.

In past times, killing unnecessarily might have been sufficient to stay the spear of any honourable Somali warrior. Somali historians confirm that acts of unsanctioned violence were discouraged by fear of cuqubo, a curse that Somalis was brought down on transgressors as a form of divine retribution. Somalis held that those who perpetrated cruelty on the helpless, holy and revered persons, would be unfailingly punished by Allah.

A half-hearted attempt to quell violence was made by Somalia’s remnant police force trying to disarm gunmen. With foresight, the ICRC supplied food to the police to inspire loyalty in the hope that banditry could be brought under control. But no one wanted his clan disarmed. Ironically, the police were not free from clan strictures. And were forced to pay an extortionate death tax. On one police search mission, several looters were killed by the police. Clan elders, backed by their own clan gunmen demanded US$7,000 for each casualty incurred, stating “while you were stealing our guns”. The police paid.

Another battle was also underway in Somalia’s interior, one that would take tens of thousands more lives by precipitating famine [and eventually US involvement]. Months after Barre was forced to flee to his home area in south-central Somalia, he regrouped fighters of his Marehan clan and counter-attacked. His forces began moving, ravaging farms and food stocks for 6 months during unsuccessful attempts to regain power. Barre’s three divisions despised the region’s “lower” farming clans and abused them accordingly.

The Marehan laid waste to the area, turning Somalia’s traditional bread basket into a wasteland. The tactic was the harbinger of the tragedy to come: it turned food into a strategic weapon and resulted in famine.

The actions of Barre’s divisions gave Aidid a chance to widen his power and conclude unfinished business with Barre. At one Mogadishu elders meeting in September 1991, he turned it into a political rally, using his military strength to win support.

The elders informed Aidid of the tales of war they were losing in the interior. Baidoa had fallen to Barre and further losses could threaten Mogadishu. Aidid confirmed he would reassess his arsenal, would meet with other warlords and respond. For Somalia’s strategist warlords, plotting every nuance of claim to power was done quietly, aseptically, without pause for ensuing human suffering, the weapon was enough.

The UN

The UN stayed away from Somalia for spurious reasons when its involvement was required. At the time of Barre’s fall, Somalia was one of the most aided countries. Being the largest distributor of “aid”, the UN left the country and was virtually the last donor to return. The UN’s bad judgement was a prelude to the screw-ups that would later turn, at that time, the largest, most expensive UN “peacekeeping mission” in history into a fiasco.

In September 1991, already absent from Somalia for 9 months, the UN tried to regain a foothold without consulting any of the relief agencies on the ground about “warlord protocol”. The UN were seen to fête the wrong powerbrokers, and within days, UN-hired security guards were killed in a political hit. Instead of recognising their mistake, UNHQ in New York declared Somalia too unsafe and banned staff from going. UN Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa, Sierra Leonian James Jonah admitted defeat by a government that didn’t exist stating, “We were advised by the President [sic Ali Mahdi] not to go back”.

At the end of 1991, UN SG Perez de Cuellar finally announced his “profound shock” Somalia was engulfed in a “nightmare of violence and brutality” and despatched his hapless envoy Jonah, to again try and make peace. This was during the last few days of de Cuellar’s stint as SG.

Jonah’s next effort was again dogged with incompetence and did further damage. He was forced to land 60 miles from Mogadishu because of “security problems”, then played the ignorant neophyte. Accompanying UN senior staff insist he allowed his visit to be manipulated by Aidid and then issued a hasty statement on the prospects of a ceasefire which increased tensions further. As a result of his refusal to meet other factions/warlords, the airport was shelled heavily during his visit and was later closed for 10 days, collapsing wider aid operations. This further underscored the UN’s lack of interest. UN “Somalia” officials working comfortably in offices in Kenya, from which they wrote press releases from “Camp Nairobi”. They described their “important work” in Somalia, economized the truth when they portrayed officials as being on quick turnaround visits to Nairobi from Mogadishu, where in fact they had no offices to begin with. Despite increased calls for action, the jobs of bureaucrats were in jeopardy. ICRC made an exception to its usual rule of silence when one ICRC delegate asked, “How come UNICEF has 43 people in Nairobi and no one in Somalia?” The UNICEF response was, “In a situation of war, we don’t operate, despite having done everything under the sun to aid war victims.” As a usual arse covering measure, UNICEF added, “Conditions now call for urgent measures, we want to relieve the suffering.”

By March 1992, the bumbling UN efforts did finally coincide with Somali war fatigue, with UN standing over the signing of a ceasefire. SE HoA Jonah conceded to having doubts that peace had been achieved and that noncompliance would be a serious matter. In fact the warlords had their own agendas and signed two separate documents that each embellished their own respective titles of “President” and “Chairman”.

To mark the accord signing by Ali Mahdi, a mortar round from Aidid’s militia hit the adjacent building where the signing accord was taking place.

© AW Kamau 2023