Third in a series by my uncle John Alldridge. This article first appeared in the Derby Evening Telegraph in December 1967 – Jerry F

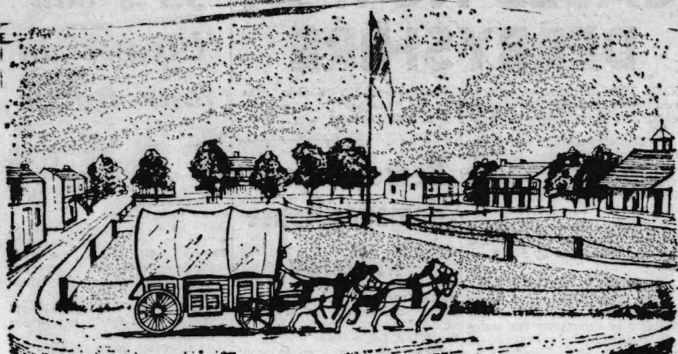

Fort Kearny,

© Reach plc, courtesy of The British Library Board – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

From Alcove Springs, in Kansas, to Fort Kearney in Nebraska is about 150 miles.

Today it is a country of large farms and little towns which proudly boast their three-figure populations as you drive in; where it always seems half-past three in the afternoon and where, if you stop for gas or a quick Coke they come up to look you over, as if you had two heads, and ask, curiously: “Where you folks from?”

A hundred years ago it was still an open desert of sandy, grass-covered hills. There are wind-breaks now, long lines of young pine trees, that act as natural shelter belts against the high winds of the prairie.

Picking their tortuous way along the crests, the prairie schooners caught the full blast of those gale-force winds that stung eyes and bare arms like grapeshot, and set their canvas billowing.

So they rolled down to the Platte River and the shelter of Fort Kearney.

The fort is now a national monument, and Ted Stutheit, the warden, is doing a fine job of restoration.

He has built a handsome stockade of pine logs around the old parade ground, complete with rifle slits and a lookout bastion at each corner.

The Army blacksmith’s shop has already been put back, brick by brick, and one by one the other buildings — the officers’ lines, the sergeants’ mess the telegraph office, the quartermaster’s store — will rise again.

But none of this was here when the wagon trains came through in the ’40s and ’50s.

A correspondent of the New York Herald, passing through in 1857, found it a collection of “five unpainted wooden houses and two dozen long broken down sod buildings built round an open square or parade ground.”

The defences consisted of “16 block-house guns, two field pieces, two mountain howitzers, and one prairie piece … the barracks has never been finished and is now in bad order. It can accommodate very well 84 men. There are in it now about 100 men.

The remarkable thing is that, surrounded as it was by tribes of potentially hostile Indians, and so weakly defended, the fort was never attacked.

It was not until the late summer of 1864 — when a wave of violence broke all along the Platte and Little Blue rivers in Nebraska when wagon trains were attacked and plundered and road ranches and stage stations burned — that the fort’s defences began to be hastily put in order.

While earthworks were thrown up in anticipation of attack, freight trains and wagon trains were held up at the fort until there were enough of them to defend themselves.

The attack never came and in 1871 Fort Kearney was abandoned to become in a few years — like so many other famous old West forts — no more than a few grassy mounds on the vast prairie.

But miserable though it was to emigrants moving West, Fort Kearney was still the last link with civilisation.

From Fort Kearney the wagons followed the broad valley to the forks of the North Platte River, sometimes swinging wide to avoid huge herds of buffalo which shook the earth as they roared past.

Along the Platte’s southern branch it was nearly 60 miles from what is now the lively little city of North Platte to the famous — or infamous — “California Crossing,” where they double-teamed across the quick-sand bottoms and then turned north to the Platte’s upper fork.

Today the new four-lane expressway gets you there in under an hour. But it took the wagons four days of gloomy foreboding.

For California Crossing, with its stories of wagons sunk or left abandoned in the sands, had an evil reputation.

Mark Twain, riding west on the Overland Stage in 1861, had to cross that shallow, yellow, muddy South Platte, with its low banks, its meandering flat sandbars and pygmy islands.

He remembered it as “a melancholy stream struggling through the centre of an enormous flat plain, only saved from being impossible to find with the naked eye by its sentinel ranks of scattering trees standing on either bank.

“The Platte was ‘up’ — they said, which made me wish I could see it when it was down, if it could look any sicker or sorrier … Once or twice in midstream the wheels sunk into the yielding sand so threateningly that we believed we had dreaded and avoided the sea all our lives to be shipwrecked in a mud wagon in the middle of the desert at last.

“But we dragged through and sped on towards the setting sun.”

Just west of Brule — between a gas station and a row of motor cabins — you can see clearly where the wagons paused after that back-breaking tug-of-war.

The ruts twist and turn in one vast parking lot; then reform and wind wearily over one more bill.

We caught up with them again 40 miles further on. In a wooded dell with a stream running through it called Ash Hollow, a natural shelter from the wind and the everlasting sun, cut into the bluffs above it. Even today it is a refreshing place.

To reach that sheltered oasis they had to work their wagons through hub-deep sand, then lower them to the valley below by ropes braced round tree trunks.

Down the side of one bald cliff, aptly named Windlass Hill, I saw the deep-etched scars left by countless wagon wheels as they skidded down the hill …

At Ash Hollow they could afford to rest for several days. There was fresh spring water, and the first game — whitetail deer, wild geese and duck — they had seen in weeks; and a river stocked to overflowing with bass and trout and catfish.

For some there was a chance to write a letter home. Somewhere about 1846 an abandoned log cabin began to be used as a primitive post office.

Letters and messages could be left there with some hope of them being picked up and carried back east.

I was intrigued to find that Mr. Paul Temple, who keeps the gas station at nearby Lewellen (pop. around 400), and is also his little town’s proud historian, offers the same service. All he asks is that letters and postcards should be stamped.

But I imagine that not many letters were written at Ash Hollow. They had been on the Oregon Trail now for over a month — a month that must have seemed for ever.

What their lives had been once was by now no more than an ill-remembered dream. When newcomers caught up with them they asked—not “When did you leave home?” but “When did you leave the Missouri River?”

We pitched our tent that night in a sandy campsite on the shores of Lake McConaughy, a straggling, rock-bound stretch of water about twice the size of Windermere known affectionately as “Big Mac.”

Aerial view of Lake McConaughy from the south,

Dicklyon – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

It was almost dark when we arrived and the camping ground was already full of trailers and caravans.

In the snack bar across the road some sociable yachtsmen were settling down to a late-night party. The jukebox ground out Elvis Presley.

I walked down to the lake, now silver in the moonlight, and stared across the water. From a cliff on the far bank two gigantic caves stared back at me, like blind and empty eyes.

They say there are Indian wall paintings in those caves, so old that the oldest living Indians cannot understand them ….

NEXT: The wild women of Wyoming.

© Reach plc, courtesy of The British Library Board

Jerry F 2022