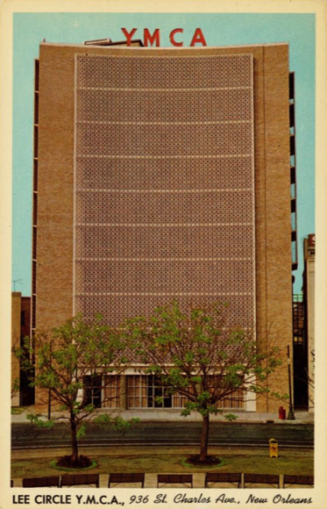

Lee Circle Y.M.C.A., 936 St. Charles Ave., New Orleans, Cliff Smith YMCA Postcard Collection – By kind permission of Springfield (Massachusetts) College Archives and Special Collections

In his seminal commencement address to the University of Texas’s excited class of 2014, US Navy SEAL and four-star Admiral William H McRaven reminded his audience that, if they wanted to change the world for the better, they must make their beds, stand up to bullies, never give up, re-spect everybody, find someone to help them paddle and be prepared to rely upon the goodwill of strangers. We shall call our stranger ‘Claude’. He was black. He was seven-foot tall. Not all heroes wear a cape, Claude wore pink Mini Mouse pyjamas. I owe him a debt. This involves a YMCA. Let me explain.

The Young Men’s Christian Association constructed its first modern New Orleans building at Lee Circle in 1929 at a cost of $423,500 dollars. I am indebted to Mr Cliff Smith who donated his collection of ten thousand postcards, dedicated to YMCA buildings and their associated activities, to the Boston digital library’s commonwealth project.

The reverse of Mr Smith’s card of the 1929 New Orleans building describes a gymnasium, swimming pool, handball courts, solarium, club rooms, living rooms, lounges and lobbies. According to the New Orleans YMCA website,

“This inaugurated an expansion of services and new facilities that paralleled the growth of the city and the greater metropolitan area. By the early 1980s, the YMCA of Greater New Orleans was one of the largest and most successful YMCA’s in the country.”

Part of this successful trajectory was the rebuilding of the Y in the early 1960s. Architects Roessle and Von Osthoff designed a ten floor, 130ft high building in the regional modernist style. The frontage was of a south-facing concrete concave construction, clad with a solar screen of patterned cast stone for privacy and protection from the sun.

Nine floors were occupied by accommodation for 186 young men, in a dormitory layout. ‘Dormitory’ was meant the American sense of the word, landings of individual rooms with some shared facilities. These shared facilities included a communal shower room. On the other floor, the ground, were classrooms as well as social and meeting rooms. The front of Mr Smith’s postcard of the 1960s building sits at the top of this article. The reverse reads as follows,

“The A.B. Freeman Memorial Residence offers the finest air-conditioned overnight or permanent sleeping accommodations to be found anywhere. Residents have access to the heated swimming pool, double gymnasium, handball courts, as well as weight lifting and special exercise rooms.”

All well and good, however, ominously, the New Orleans YMCA website’s potted history continues,

“But, in a continuing parallel of the city’s trajectory, the YMCA experienced a period of contraction and consolidation beginning in the mid-1980s as corporations began to leave New Orleans and the population and philanthropic base declined.”

Even more ominously, it was during this nadir that your humble author landed on them. Did I just write, ‘communal shower room’? Yes, I did. I had an excellent friend, an officer in the Parachute Regiment. After many years of contemporaneous but separate derring-do, I caught up with him again. In the intervening time, we had both ‘done’ America. He couldn’t help but recall that, upon staying at a YMCA in New York City, all of the shower curtains had been holed at genital height.

“Shower curtains?”, I replied, seated beside a roaring log fire in the safety in a northern English country pub, our mountain bikes propped against a dry stone wall in the adjoining 17th-century Meeting House Lane, “Lucky you.” The showering facilities at the YMCA in New Orleans were completely communal. Every single joke that every single Puffin has ever heard which includes the line, “Excuse me sir, you’ve dropped your soap,” is based upon fact. Puffin in distress.

In the noise and commotion, I was rescued very quickly. The navy SEALs would have been impressed. A fireman’s lift and a sprint down a corridor got me back to my room and put me straight (so to speak), as did an ensuing pep talk on YMCA dos and don’ts. Claude, I thank you and salute you.

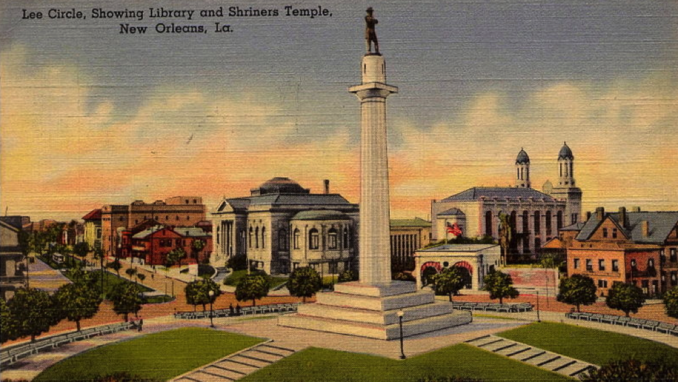

Lee Circle, a park in New Orleans, No photographer credited – Public Domain

On the above postcard, Lee Circle is represented as it was between the wars. Just to the left of the Lee Monument, we can see a neo-classical building. This was the main branch of the New Orleans public library. Built in 1908, it was funded by American Scottish steel industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie who donated 2,500 libraries around the world between 1883 and 1929.

Previously the site had been occupied by the Saenger Halle, a theatre for the German singing society. The library was in turn demolished in 1959, having been sold after a new library had been constructed at Loyola Street.

By 1961 a concrete and glass stump, a John Hancock building, sat in its place. The Boston based insurance company were responsible for the construction of a number of notable buildings about that time. You will have seen the John Hancock Centre in Chicago. It is slopey black and topped with two white TV masts. At the time of construction this, at 1128ft, was the second tallest building in the world. Hancock’s architects were Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill who provided a more modest structure for Lee Circle, seven stories high, built upon a raised terrazzo plaza.

In 1974 the Besthoff family purchased the building to serve as a corporate headquarters for their K & B drug store chain, thus it was renamed the K & B Plaza. When K & B subsequently sold out to Riteaid, the Besthoff family retained parts of the building. Valerie and Jane managed their real-estate interests from there, Sydney Besthoff III displayed his art collection to the public.

The Besthoff’s also owned the neighbouring twin byzantine towered temple Sinai synagogue. Built in 1872 and seen to the right of the old library. In 1885 William Head Coleman, in his “Historical Sketch Book and Guide to New Orleans and Environs”, described the synagogue in these terms,

“Temple Sinai, Jewish, a graceful and most imposing structure, ……. is, without a doubt, the most beautiful edifice of the kind in the United States, combining grandeur with simplicity so appropriately that the beholder is charmed.”

In 1928 the Mount Sinai congregation moved elsewhere and the Motion Picture Advertising Company acquired it to use as their headquarters. In 1977 the synagogue was demolished to provide a parking lot for the neighbouring K & B Plaza. However, the twin towers survived. Salvaged by businessman Theodore Bottinelli, they sit on top of a former warehouse in nearby Bottinelli Place. Perhaps because of an inherited eye for a good piece of masonry? Theodore’s father, Teodoro Francesco Bottinelli, had been born in 1886 in Brenno, Italy, had immigrated to New Orleans and worked as a sculptor.

Jeruselem Temple Building, St. Charles Avenue, New Orleans., Infrogmation – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

To the left of the library and about a block along St Charles, an orange building can be seen. This was the Shriners, or Jerusalem, Temple. Designed in a Moorish style by local architect Emilie Weil, it was built in 1918 for the ‘Ancient Arabic Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shriners’, a masonic fraternal association.

Slightly older Puffins may recall Fred and Barney Rubble in their water buffalo hats. Very old puffins may recall Abbott and Costello and Bob Hope in outrageously outsized fez’s covered in odd symbols. That’s the kind of thing. Carolyn Kolb describes the place in its heyday,

“The Jerusalem Temple had an auditorium suitable for Carnival balls, plus a large room on the ground floor that could also be used for dances. As you entered, you could read an intriguing sign: Glad-U-Kum. The sentiment was kindly meant, and the pseudo-Arabic spelling was dear to the hearts of the building’s owners, the Shriners.”

Latterly, it has become the Church of the King and has been used for religious services and homeless outreach.

In front of the synagogue, bordering Howard Avenue, can be seen a twin arched frontage topped with an American flag. This was the Sherrouse-Steele Motor Car Company which sold REO and Premier vehicles. You may have heard of one of REO’s trucks, the Speed Wagon. A friend tells me that a popular music combo are named after it. Although those two makes are now long gone, astonishingly the garage remains.

By the 1950s it had become a Texaco outlet. In the modern-day, almost a century after the above postcard reproduction, it is an Exxon gas station with a K Mart convenience store attached. Three decades ago, before the invention of the credit card operated digital gasoline pump, a cute black girl sat there all night in a bulletproof cubicle beside the cash till. We shall call her ‘Trinity’.

We were sweet on each other but our styles were cramped. At night, she was locked behind a three-inch thick kevlar impregnated glass screen. By day she slept. Simultaneously, I was only allowed out of the Y when it was boiling hot or when there was torrential rain, i.e. when they’d be no one hanging around the crack house. Myself and Trinity had nothing in common but developed the kind of friendship that might emerge between two prisoners or a pair of random strangers trapped on a desert island. Many a successful marriage has been based upon such. Our whispered confidences would go something like this,

“Trinity, people our age grew up with the Kennedy Camelot myth thing. Wait till you hear this. If you look over to the left of the Y, that’s Andrew Higgins Boulevard, a short walk, 50 yards, takes you to Camp Street. Take a left and, another short walk later, you’ll be standing outside number 544, the one time offices of the ‘Fair Play for Cuba Committee’.”

“Uh-huh? Do you play any sports?”

“Likewise, walking along the street to the right of the Y, takes you to the intersection of St Charles and Canal, where, on August 9th 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested following a scuffle over his ‘Hands Off Cuba’ leaflets. Leaflets that were stamped with the address ‘544 Camp Street’.”

“Yeah? What’s your favourite TV show?”

“Trinny, while at Camp Street, you may have noticed that 544, being on a corner, is the same building as 531 Lafayette Street, the former business address of a certain Mr Guy Banister, private detective. What do you make of that?”

“It’s stopped raining hunni, you’re gonna have to get back to the Y.”

1959 Guy Banister Associates, Inc. Yellow Pages advertisement, 959 New Orleans LA USA Telephone Directory – Public Domain

Upon hearing such a tale, a Parachute Regiment officer might have been tempted to remark, “Bloody Kennedy, bloody Irish, bloody Catholic, bloody Communist, bloody Democrat, bloody American, no wonder they bloody shot him.” Words that could have come straight from the mouth of Mr Guy Banister, private detective, himself. It would have made a good film. It did, subsequently Oliver Stone released “JFK”. They heard it all first from a Puffin.

Next Time: Where Howard intersects with Charles, where we can see Lee’s Circle, where there’s a YMCA with a communal shower, is there a really a need for a Seaman’s Hostel? You bet there is.

Acknowledgements

Carolyn Kolb, MyNewOrleans.

Kezia Kamenetz, OnlyInYourState.

Jeffrey Monseau, Springfield College Archives.

New Orleans Museum of Art.

Nicole Shea, Boston Public Library.

Old-New-Orleans.com

The Times-Picayune / The New Orleans Advocate.

The Tulane School of Architecture.

The YMCA of Greater New Orleans.

Wiki.

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player