© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

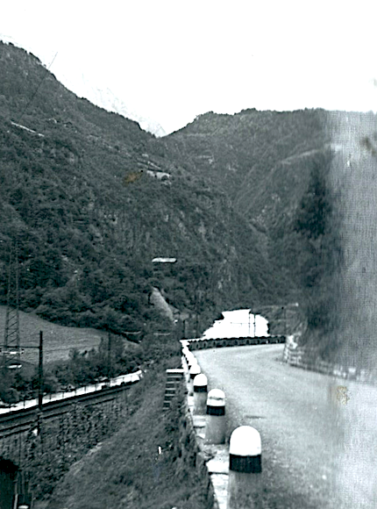

Here we see caped cyclists rolling downhill from the Brenner pass summit which marks the border between Austria and Italy. The sign to the left, in both English and German, reads ‘Good bye again in Italy’ which doesn’t make a lot of sense but, given the order of the photographs, suggests we’re on the Italian side of the frontier looking over our shoulders having just left Austria. To the right is the Brenner railway line and to the right of that what we will come to suspect to be a standard issue Italian customs building.

The painted bollards opposite are, presumably, topped in white to be visible in summer and banded in black to be visible during the lighter coverings of Alpine snow. Judging by the rail track catenary (overhead wires) this is a double-track section of line. Given much of the Brenner Railway at the top of the pass is widened by passing loops and sidings this assists us in having a stab at finding the exact point where the photograph was taken.

On Street View the snow intervenes and any distinctive kerbing has been replaced by crash barriers but given the shape of the hillsides, I would hazard a guess at the location being here or hereabouts on the Via del Stazione about a mile into Italy.

There is no sign of the customs building on the right, with aerial photography showing a modern-day truck park near the Plessi Museum. If you pan to the right you’ll see one of those rolling road rail services which carry train loads of trucks through the mointains. The summit itself is much changed since my father and grandparents’ 1954 visit. As a major Northern Europe – Southern Europe transit route, a four-lane mega highway, the E45, supplements the original road. The Brenner summit itself is now disappointingly crowded with retail outlets, motorway services and other nondescript boxes, rather than an empty road peppered with adventurous caped cyclists.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

With those distinctive bollards, a river, railway line, stone bridge and captioned ‘The Dolomites’ the above location should be findable. From the summit down to the town of Brennero there is a lack of a suitable river but after the Trolyean town, the Iscaro (Eisak in German) joins our route as far as Vipiteno, home of Italy’s 5th Alpine mountain regiment. After that, we leave the railway line and follow a very interesting route to Merano. Ordinarily, one would hesitate to make that assumption but given my grandfather’s earlier track record in the Pyrenees, one would wager that’s where the Gods of mountain passes and old jalopies tempted him. Fortune favours the brave and all that.

Having already admitted, despite my farmery ancestry, that I know nothing about hosses and beasts and can’t tell the difference between hay, straw and silage, I must now confess that I’m essentially a hill and lake man who knows little about big piles of dry and big holes full of wet. The internet tells me the Dolomites are a mountain range located in Northeastern Italy that form a part of the Southern Limestone Alps, which in turn are part of the European Alps that run in a large crescent from France through Northern Italy, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia. The Dolomites extend from the River Adige in the west to the Piave Valley in the east. The northern and southern borders are defined by the Puster Valley to the north and the Sugana Valley to the south.

Additionally, the fantastic scenery is due to the Dolomite’s geology. Jagged and distinctive mountain peaks are not only quite strange and unusual compared to our own Lake District, but even to the rest of the Alps and other Northern Hemisphere mountainous regions.

As we saw in the previous instalment, as we were drawn ahead of ourselves at the prospect of a grisly murder near Hapsburg Prato Allo Stelvio, we’re heading for the Adige river which flows westwards away from Verona and Bolzano along the Venosta valley. En route, we will pause again at the Hotel Posta as it holds an interest beyond pennyless French barrister adventurers murdering their wives for an inheritance.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

© Google Street View 2022, Google

As well as for the gastronomy of the Hellenstainer hospitality dynasty, the Posta was also famed as a sports hotel in a region popular with Alpine sports enthusiasts. Outside of the modern hotel you can see silhouette statues of a runner, a walker and a cyclist but not of a motorist. An important omission. There is space to the left for a Bentley Open sports Tourer, perhaps driven by Mr Toad. For looking through old newspaper cuttings reveals another Alpine sport, possibly the inspiration for my grandfather’s odd routes both here and on the trip to Spain and South West France – hill racing. The Hotel Posta was used as a starting point during the Alpine hill racing season. Local correspondents excitedly syndicated their stories to the world’s press. The following appeared in the Dublin Herald on the 4th of September 1926,

The new Alpine motor race, run in the Italian Tyrol on last Saturday, is said to have eclipsed anything in the way of sensational and interesting road races yet run. The race is up a perilous mountain road known as the Trafoi-Stelvio road which attains an altitude of a mile in the course of twenty-seven kilometres of tortuous curves and zigzags that separate Trafoi at the mountain’s base from Stelvio Pass at the top.

The correspondent goes on to tell us that this was the second time the race had been run having been inaugurated the previous year to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the building of the road. Its success led to the competition becoming an annual event. Organised by the Italian Automobile Club, as well as daring-do for drivers the race also provided the cars with ‘a gruelling dash up the mountainside’ causing ‘carburation’ on account of the rapid rise from 800 yards above sea level to over 2,700.

Puffins paying attention may be interested to hear that it was on one such curve near Trafoi that last week’s dastardly M. de Tourville pushed his wealthy ‘suicidal giddy wife, prone to seizures’ to her death.

The late summer season of Alpine hill challenges included some starting from our Hotel Posta at Spondigna. Contemporary newspaper reports recall the races as quite an event. The mountain slopes were dotted with spectators. All the population of the Upper Adige migrated to the mountaintops. Whole families came in carriages, the wealthier in their motor cars. Tyroleans wore picturesque local costume. Tourists arrived from Merano, a nearby leading summer resort. An eyewitness wrote,

The course itself bisects one of the most beautiful regions in the Italian Tyrol. The Stelvio Pass crosses the Dolomites which form a natural as well as a political boundary between Italy and neighbouring countries on [to] the north. For background the course has an inspiring variety of mountain scenery from tall precipices to smooth glassy [grassy] slopes. The motor road is so high that it is open [to] traffic only during two or three months of the year – normally from July 1 to the middle of September.

Although your author is aware that those who live in grünhäuser shouldn’t throw jagged lumps of granite, one feels obliged to observe, despite it being almost a century ago, the patriarchy was already struggling to impose the colonial fascism that is the right words in the right places, correct spelling and the use of enough commas.

Entry #80 in the III Stella Alpine in on August 4, 1949.,

Unkown photographer – Public domain

As for the route from the Hotel Posta at Spondigna, it held thrills that would be difficult to duplicate on any other course, making the race one of the most dangerous and dramatic in the world. A fairly level start ran for several kilometres to Prato where a winding climb ran through the mountains to Gornagoi before the spectacular part began in earnest at Trafoi. Competitors addressed hairpin and corkscrew rises via a series of thirty sharp zig-zags rising 3,000 feet while, to the side of the road, precipices dropped abruptly hundreds of feet. A fractional error of judgement or a slip of the hand on the steering wheel might send a car hurtling through space.

Despite the danger competitors took these stretches at a startlingly high speed, showing [slowing] up only when rounding the sharp angle of the curve itself. Sometimes where the turn happens to be banked by a rocky wall or projects into the end of a narrow ravine, the drivers do not slow up at all. Jamming the steering wheel to one side, they allowed the rear of the car to be swung around by the momentum of their charge.’

Alpine motor racing resumed after the war with the administration of such being dominated, as was Formula One’s FIA, by the French. Although the emphasis was on the French Alps, official races were also held in Austria and Italy. The heyday was the 1950s, perhaps inspiring my grandparents and father to follow their unusual route. Models such as the Renault Alpine, Sunbeam Alpine and Crysler Alpine were inspired by the glamour and bespoke engineering required. Formula One’s Alpine F1 Team began life in the early 1950s as the Société des Automobiles Alpine SAS. Founded by a Dieppe-based Renault dealer, Alpine originally modified Renault 4CVs to compete in the Coupe Des Alpes and the legendary Brescia-Rome-Brescia Mille Miglia.

Puffins will be relieved to hear that we’re not going that way, rather straight past the road end at Spondigna in the direction of the border at Tubre. There we will enter an early post-war Switzerland very different from the present day or even that encountered by the staff at Going Postal (entirely independently of each other *taps nose*) many decades later.

© Always Worth Saying 2022