In August 1948 my uncle, John Alldridge, reported from Germany on the steps that the British Army was taking to combat high levels of illiteracy in the ranks – Jerry F

Unknown artist – © Reach PLC

The young soldier stood to attention before his commanding officer while the sergeant-major read out the charge against him. In defiance of company orders he had absented himself from barracks when the battalion was confined to camp in preparation for a sudden move.

The commanding officer, a tolerant man and one wise in the ways of young soldiers, looked at him thoughtfully for a moment and then asked: “Have you any excuse?”

The young soldier’s stolid composure suddenly broke down. He blushed a fiery red, licked his lips, and finally stammered, “I’m sorry, sir, but I didn’t understand the order. You see, sir, I can’t read.”

That was in 1944, in the last year of the war, when the Army suddenly woke up to the dismaying fact that it had on its hands 10,000 young men who had the educational development of a healthy five-year-old.

Today the problem is only slightly better. A survey made shortly after the war showed that 12 per cent of children leaving school had a reading age of under eight and a half years. These children were the creatures of circumstance. They were the unfortunates whose education was interrupted by war, unlucky little evacuees, forced to pick up their learning where they could in overcrowded classes from harassed overworked teachers; or, worse still, denied schooling altogether “because dad was in the Army and mother needed me at home.”

In its approach to this problem of the illiterate soldier the Army is showing commendable tact. It is, for instance, extremely careful how it defines that word “illiterate”. For Army purposes an illiterate is man “who can make little or no effective use of reading and writing; for practical purposes a man who cannot complete his personal record sheet even under instruction.”

Wherever possible these unfortunates are sorted out as soon as they join the Army and drafted in squads of 50 at a time to one or other of the Royal Army Education Corps’ five schools of preliminary instruction. Here they undergo a six weeks’ course, which must be unique among Army courses.

For the first problem facing the instructor is how to break down a man’s newly discovered feeling of inferiority. He comes to the school suspicious, resentful, aware for the first time of being somehow different from his fellows.

Each school tackles this problem in its own way. At the Rhine Army School the chief instructor is overcoming it by suggesting to the pupil on arrival that he is not at school at all. Classrooms are recognised only by each having a different coloured door. Individual classes are small – rarely more than five to a class – and each under the whole-time supervision of an instructor who is as much a psychologist as an educationalist.

These instructors have found that the intelligent illiterate, in his first contact with education, is subject to periodical attacks of depression. So on every possible occasion pupils are encouraged to take part in what the school ambiguously calls “functional training”. This means that when the mood is on him the soldier can leave the class and dig for an hour in the garden, or chop wood, or feed the hens.

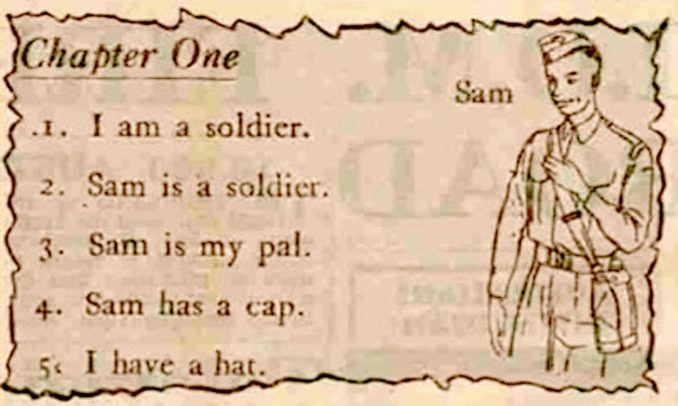

No school in the world can do very much in six weeks. So the Army’s schoolmasters sensibly concentrate on rudimentary essentials. The six weeks’ course is centred around the letter. If by the time the soldier leaves to rejoin his unit he can write a simple letter by himself the school feels that it can chalk up another success.

That may seem a little thing, but just for a moment imagine yourself for the first time in your life among strangers in a foreign land completely cut off from home because you cannot write or read a letter unaided.

Small wonder, then, that these “backward boys” show the most amazing progress: that instructors are kept working long after official school is over trying to satisfy this new-found thirst for knowledge.

Text and Picture:

The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The British Library Board

© Reach PLC

Jerry F 2022