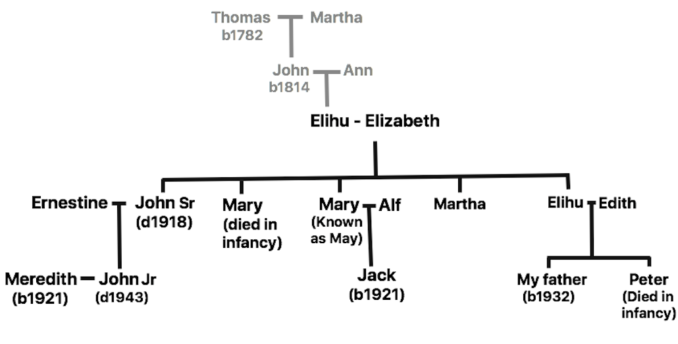

Last time, we discovered my father’s cousin John Jr gave his life for his country at Bone in Algeria in 1943. In the First War his father, John Sr, died of sickness after being discharged from the Army following an accident during a bomb-throwing practice after volunteering for a raid against the Kaiser Bill salient on the Western Front. John Sr died at 27, John Jr was 25. Both married their childhood sweethearts during the earlier stages of the wars. John Jr never knew his father.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

After the First War Ernestine, John Sr’s widow, moved on and settled in Lancaster. Likewise, two decades later, life began again for John Jr’s young widow, Meredith. After the end of the Second War, Meredith married a local man. In the 1939 residency survey, her new husband was an electrical engineer living with his mother and sisters in a tight-knit working-class community of respectable red-brick terraces close to one of Carlisle’s railway depots. Perhaps at the time of the survey, his father and brothers (if any) would be in the military and away from home while he worked on the railway, a reserved profession, exempt from military service? After marrying, the happy couple moved to another railway town, raised a family and lived to a ripe age.

Like so many other bereaved families and young widows in the grim years that follow every war, one imagines Meredith and Ernestine continuing their new lives without complaint, aware of many others, in every corner of the land, Commonwealth and Empire in similar or worse circumstances.

However, as I turned the pages of my family’s Nostalgia Album – forward towards sunnier times, backwards to my father’s uncle Alf’s interesting Great War – a doubt nagged. Although Ernestine had moved to Lancaster, her surname remained the same, suggesting she hadn’t remarried. Her parents were from the West Country and had moved to Liverpool where Ernestine had married John Sr and bourne John Jr. Her son married a Carlisle girl, not a young woman from Lancaster or his native Liverpool. John Jr’s best man was a cousin, a Carlisle lad called Jack.

Mention of which drew me back to a sepia newspaper cutting, mentioned in a previous episode, celebrating my great grandparent’s golden wedding on Christmas Day 1938. Recalling John Sr (with no mention of the war) fleetingly as ‘Another son who died in Liverpool some years ago’, the article added, ‘Surviving children, together with three grandchildren – all boys – will celebrate the anniversary on Christmas Day’. Those three boys were my father, aged 6 in 1938, Jack (18) and John Jr (20). A fourth cousin, who will take us to those sunnier climes, wasn’t born until seven months later.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

With the frustration of the amateur genealogist who should have asked a thousand questions of the living when he had the chance but didn’t, does this suggest all three boys are in Carlisle rather than John Jr being with his widowed and single mother in Lancaster or his mother’s family in Liverpool?

By now, Puffins will be more familiar with my family album than was I before beginning this research only few weeks ago – originally for a light-hearted piece about my grandfather’s motorbikes. Puffins will also have heeded a couple of oblique references to the family deed box, a stout contraption, all secret compartments, inkwells and hinged writing slope. It minds its own business in the attic under my model railway, guarding its collection of half hints pointing towards our family’s hidden truths.

Besides the album and the deed box, there is a family Bible. As I type, it sits behind me on my office shelves demanding centre stage. Firstly, I must describe its own Genesis. With the eldest son and his son being killed in the wars, when the time came, the family Bible was passed to the eldest remaining daughter, Mary (known as May). Her husband was Alf, her son was cousin Jack.

I knew Jack. He was a character. As my grandfather Elihu’s interest in motorbikes was contagious, Jack was bitten by the bug and would compete with my father and grandfather in trials and scrambles. Ten years older than my father, Jack was the elder brother he never had (there was a younger brother who died in infancy and was never mentioned).

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Like his uncle Elihu, Jack became a fitter and worked in the local gypsum mines. In the halcyon days when gypsum miners could afford a shiny new Jaguar Mark II gangster car (kept on a concrete set drive next to an asbestos garage beside their parent’s council house), we’d spot a garden full of Jack’s projects. Not only bikes and cars but cement mixers and worse, in fact, anything with an engine. Although never married, he was engaged for decades to another Mary and had another house, fully furnished, empty and gathering dust, awaiting a happy day that never arrived.

As they ran the gypsum mine down, people left in ones and twos. Every Friday for two years, Jack contributed to the whip-round as other men moved on. Having the most important job in the mine, he was the last to go. He was the one who had the privilege of locking the place up for the final time. The downside being, there was nobody left for a whip-round and he got nothing. A life lesson there.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

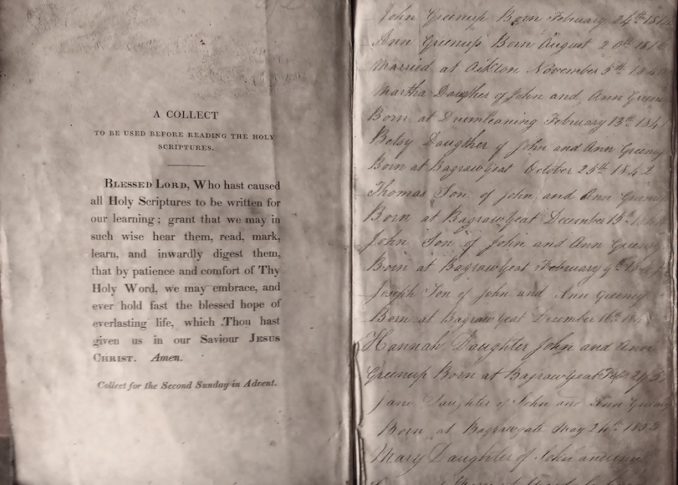

After the mine closed Jack retired and, as the generations threatened to pass once more, one brisk Saturday morning saw the Gangster Jag purring outside our house while I was presented with the family Bible.After opening the stout leather cover and turning a blank and yellowed flyleaf, the first of our family’s handwritten registry was revealed. Beginning on February 24th 1814, 14 months before the Battle of Waterloo, the record starts with the birth of my 2nd great grandfather, also called John.

A fine and disciplined hand notes his wife, Anne’s, birthday and then their wedding at Aikton, near Wigton, at the 12th-century church of St Andrews. Over two hundred years later, myself and my children have stood in its porch and enjoyed the view afforded of rich pasture leading to distant mountains. Beside the entrance is my great great great grandfather’s headstone. Impressively taller than me, it marks the resting place of, according to the 1851 census, a farmer of 155 acres with two servants. I consider him, Thomas, a gentleman farmer and assume he was addressed by all and sundry, both to his face and behind his back, as ‘Mister’ Worth-Saying.

Aikton Church,

John Holmes – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The Bible is dated 1843 with the handwriting suggesting the prior entries were written ‘in arrears’ in one sitting with the latter ones made by the same hand but added as John and Anne meandered across Cumberland’s tenanted farms while being blessed with ten children. At one point, they farmed adjacent to Mrs AWS’s ancestors. Beside a hillside stream that gargles in the summertime, rages in spring and autumn and sits frozen between those two seasons, both sides of our family lie in the same graveyard separated by a certain follower of hounds, who y’ may ken, called John Peel.

In my present bald and dilapidated state, friends and total strangers point out I have a head like a skull. With the same spirit of effortless unthinking self-evidence, my wife insists we must be related.

The Bible can be challenging work. Difficult to understand in part, open to different interpretations, it contains redactive passages part dependant upon the standpoint of the writer. Likewise with the entries on the inside front pages of this King James Version, printed by John W Parker, University Printer, on behalf of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

For the next generation the hand changes. Presumably, it is that of my great grandfather, also an Elihu, or his wife Elizabeth. Then it changes again, to Aunty May’s, (Jack’s mother and my great aunt).

Although Aunty May records her own and her other sibling’s marriages and births, puzzlingly she makes no mention of her brother John Sr’s marriage to Ernestine and no mention of the birth of John Jr. One more glaring contradiction jumps from the page, appropriately relating to the Christmas Day wedding. As proof of both the existence of God and that nothing changes, it echos a discrepancy repeated 1,045 pages later in Matthew Chapter 1 Verse 18 when the early days of St Joseph’s betrothal to yet another Mary got off to a scandalous start.

© Always Worth Saying 2022