Introduction

It is interesting that in Monty Python’s ‘Life of Brian’ when Reg , the leader of The People’s Front of Judaea, poses that question the very first response he receives from his gang of activists is ‘the aqueduct’ followed closely by ‘sanitation’. 2,000 years ago, at a time when our British ancestors were living in wattle and daub huts in comparative squalor, the Romans were constructing monumental works of public health infrastructure in the lands that they conquered that even to modern eyes are stunningly impressive. In Britain a further 1,800 years would have to pass before our civil engineers had the necessary skills to undertake public works on a similar scale.

The Romans took personal hygiene very seriously and while in modern cultures bathing is for the most part a private function, for the Romans it was a communal activity. Even in such remote outposts as Housesteads Fort on Hadrian’s Wall (built around 124AD) at the very edge of the Empire there was a bath house and toilets with running water.

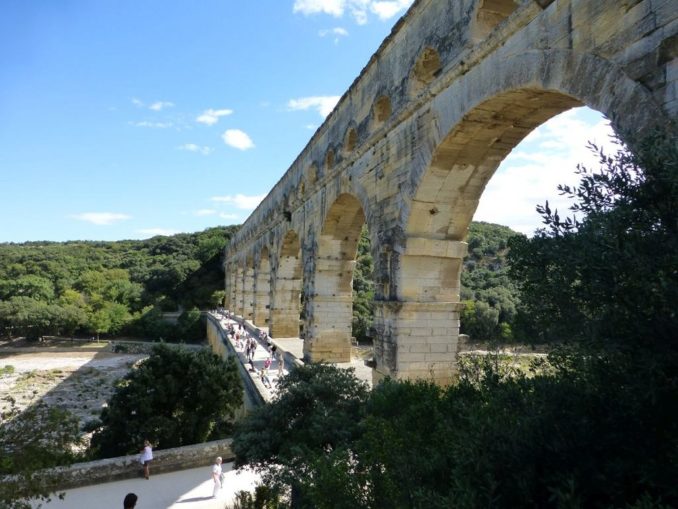

Getting sufficient and reliable quantities of clean water to settlements often posed significant engineering challenges for Roman engineers and one of the very best places to see and marvel at Roman hydraulic engineering at its finest and most beautiful is at the Pont du Gard aqueduct that spans the River Gardon in the Gard Département of the South of France mid-way between Nîmes and Avignon. With a height of 48.8m (160ft) it is the tallest structure ever built by the Romans.

The problem facing the Roman engineers

As the city of Nemausus (Nîmes) grew in the first century AD, so did its demand for water. The area to the south of the city being low-lying and flat was unsuitable as a water source so the Roman surveyors eventually decided to bring water into the city from springs at Ucetia (Uzès) 20km (12mi) to the north as the crow flies so as to avoid having to cross the difficult terrain of the Garrigues de Nîmes to the west of the city.

One of the major problems that the engineers had to overcome was establishing the gradient between the springs at Fontaine d’Eure near Uzès and the distribution basin (castellum divisorum) at Nîmes , a difference of only 17m (56ft) over a channel length of 50km (31mi). Had the engineers opted to use a constant gradient for the water channel this would have necessitated an aqueduct 6m (20ft) taller than the current one which would have been impractical. The gradient the Romans employed gave an average fall of 1 in 3,000 but in places it was as low as 1 in 20,000 with one section being laid to an incredibly accurate 7mm (0.28in) in 100m (330ft).

Over the length of the Pont du Gard itself, the fall in the channel is only 2.5 cm (1 in), a gradient of 1 in 18,241 which is remarkably precise in view of the engineers use of what, when judged by today’s standards at any rate, were very primitive surveying instruments.

At its peak, the Uzès-Nîmes aqueduct would have carried an estimated 40,000 cu m (8,800,000 imp gal) of water that was pure but rich in dissolved calcium bicarbonate to the bath houses, fountains and homes of the city every day.

Building the aqueduct

Where the aqueduct crossed land it was either by means of subterranean channels excavated, lined and roofed over with stone slabs and earth or by means of stone channels supported on arched walls depending on the levels dictated by the terrain. Much of the above ground construction was robbed in antiquity as it was a prime source of relatively easily accessible, ready-worked stone blocks for use in building projects. Nevertheless, some reasonably well-preserved lengths can still be seen along its route, if you know where to look.

Where it crosses the river valley, the Pont du Gard comprises three tiers of arches, 6 in the lower level, 11 in the middle level and originally 47 (only 35 remain) in the upper level. The stone, an estimated 50,400 tons in total, was quarried locally and delivered to the site by river. Because of the accuracy of cutting, the blocks, some of which weigh more than six tons, could be assembled without mortar. Very few metal cramps were used in the construction. Although the external surfaces of the stones were left relatively rough-hewn in comparison with other Roman buildings of the period, particular attention was paid to obtaining a smooth and impervious lining to the water channel throughout its length. The holes and projections that can be seen in the faces of the arches are supports for the wooden scaffolding used during construction. The stone blocks would have been hauled into place using sheer-legs, windlasses and man-powered treadmills.

Modern archaeological research suggests that the aqueduct was built around the middle of the first century AD during either the reign of Claudius or Nero and took approximately 15 years to complete.

History

Throughout its approximately 400 years of use, the aqueduct required constant maintenance in order to keep the channels clear of concretions, debris, roots and other vegetable matter that greatly reduced its flow and this was carried out by gangs of workers who regularly crawled along it. Recent scientific analysis of the concretions deposited inside the channel at various points along its length reveal that by the middle of the 3rd century the aqueduct had become so badly degraded that it was partially abandoned. From the 4th century onward the region was subjected to constant incursions by invaders and due to neglected maintenance the aqueduct stopped working entirely between the 5th and 7th centuries.

That the Pont du Gard itself has survived so intact is due largely to its having being used as a toll bridge by the seigneurs and later the Bishop of Uzès from the 13th century onward as they were responsible for its upkeep. Repairs were carried out by the local authorities in the early 18th century and a controversial new road bridge was constructed alongside the lower arches in the 1740s. By the 1830s, however, the Pont du Gard was in a poor state of repair and in danger of collapse. In the 1850s, Napoleon III approved restoration plans and provided state funding for the works to be carried out which included a staircase that provided access to the conduit along which visitors could walk. Unfortunately, the general public no longer has open access to the water channel although guided group tours can be booked.

In 1985 the Pont du Gard was added to UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites.

Visiting the Pont du Gard

The Pont du Gard has for many centuries been a popular tourist attraction and it was much visited by French royalty and aristocrats doing the ‘Grand Tour’. By the mid-1990s things had got so far out of hand with traffic queuing up to drive over the 18th century road bridge and the riverside areas resembling a fairground with souvenir shops and food stalls cluttering its banks that the area was cleaned up and pedestrianised. There is now a modern visitors’ centre with a wonderful museum on the north bank.

The site is located between Remoulins on the RN100 and Vers-Pont-du-Gard on the D81.

On our first visit we made the mistake of going by car and we were inside the expensive car park (15€) before we had an opportunity to turn around. If you are able to arrive on foot admission is free so for all our subsequent visits we walked there across the garrigue from our campsite using local footpaths. The museum in the visitors’ centre is well worth a visit and in hot weather the outdoor areas are shaded and misted with very refreshing water sprays. Food and drink are expensive so I would advise taking your own picnic.

While in the area don’t miss visiting the lovely medieval town of Uzès whose market is particularly lively on a Saturday morning in summer.

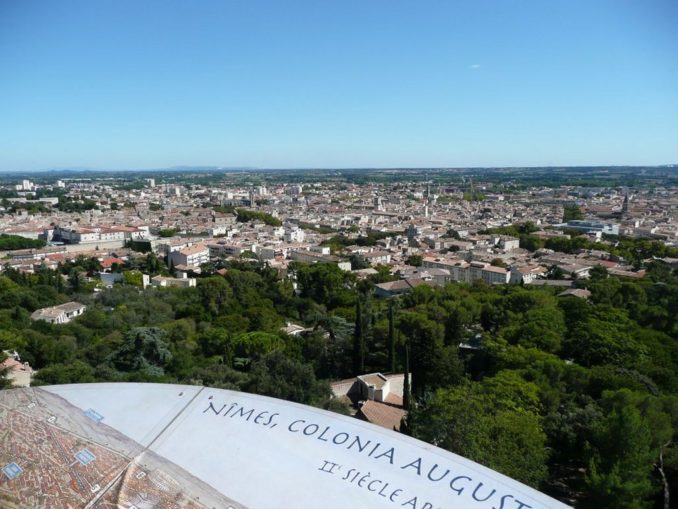

Nîmes with its beautiful parks, fountains, and Roman monuments including gates, temples, a beautifully preserved arena (used in the film ‘Gladiator’) and a viewpoint tower is also well worth a day of anyone’s time and would make an ideal touring base for the whole region.

© text & images Tom Pudding 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file