In 1954, as the centenary of the end of the Crimean War approached,

my uncle John Alldridge produced a series of articles for the

Manchester Evening News which vividly described that campaign.

In this article, the words are his; the choice of illustrations is mine.

Jerry F

Balaclava: Glory out of chaos

Of all the fantastic, ridiculous, outrageous characters who swaggered their arrogant way in and out of the comic-tragedy which history has titled The War in the Crimea, none was more fabulously absurd than Major-General the Earl of Cardigan, commanding the Light Cavalry Brigade.

Equestrian portrait of James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan (1797-1868),

Francis Grant – Public domain

Immensely wealthy, punctilious, and irascible, he was cordially detested by his officers. The smallest trifle would throw him into a quivering rage.

He was not merely a ridiculous nuisance; he was downright dangerous, for it was a period when an assertive, quarrelsome man was exceedingly dangerous.

On every occasion he demanded the rights and privileges of his rank and class.

So while the officers and troopers under his unhappy command sweated and froze in the mud of a tented camp, my Lord Cardigan relaxed on his luxury yacht, complete with French chef, six miles away.

At the time of the Crimean War he was 57, but looked no more than 30, a fine upstanding figure of a cavalry officer with a luxurious spread of tawny whiskers.

No one disliked Lord Cardigan more than his brother-in-law and divisional commander, George Charles Bingham, Lord Lucan.

George Bingham, 3e comte de Lucan (1800-1888),

D. J. Pound – Public domain

Major-General Lord Lucan was 54. “He was a sensitive man,” we read, “though he had the additional misfortune of being invincibly stupid.”

He was known to the troops in the Crimea as “Lord Look-on”, a name which he certainly earned, by his fretful, though aimless, behaviour.

To this pair of bickering blockheads was entrusted the fortunes of the British cavalry at Balaclava; a misfortune which was to result, on October 15, 1854, in the tragedy immortalised as The Charge of the Light Brigade.

Until that moment the British army, generally considered to be the finest in the world, had had a poor war.

Because the commander-in-chief, Lord Raglan, seemed terrified of committing them, preferring to keep them perpetually in reserve – “in a band box” as he put it himself – they had seen very little fighting.

The dash of British cavalry officers was never greater than at the opening of the Crimean campaign in 1854, Mrs Wood Iram-Smith tells us.

“These aristocratic horsemen were, in the idiom of the day, ‘plungers’, ‘tremendous swells’. They affected elegant boredom, yawned a great deal, spoke a jargon of their own, saying ‘vewwy’, ‘howwid’ and ‘sowwy’, and interlarded sentences with loud and meaningless exclamations of ‘haw, haw’.

“Their sweeping whiskers languid voices, tiny waists laced in by corsets, and their large cigars were irresistible, frantically admired, and frantically envied.

“Magnificently mounted horses were their passion, they rode like the devil himself, and their confidence in their ability to defeat any enemy single-handed was complete.

“Cavalry officers were saying in London drawing-rooms that to take infantry on the campaign was superfluous – the infantry would merely be a drag on them and had better be left at home.”

Now the cavalry was to have the chance! It was to be thrown headlong into one of the most heroic and most useless engagements in British military history.

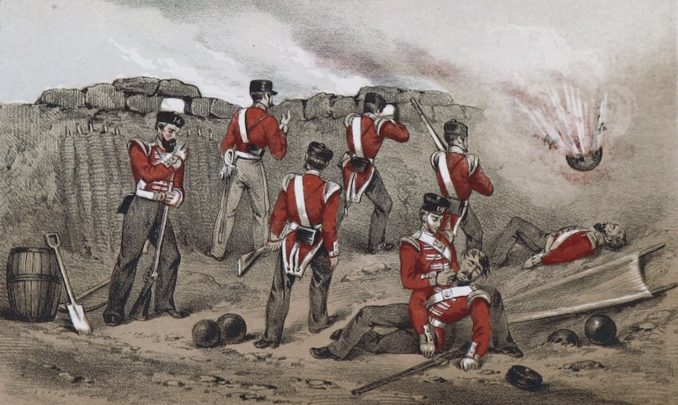

British lines under fire,

Sir James E Alexander – Public domain CC BY-SA 2.0

The Battle of Balaclava, like all the battles of the Crimean War, came about by accident.

Nobody planned it. Half the time nobody, least of all the generals commanding, knew what was happening. And when it was over nobody could tell who had lost and who had won.

On September 26 Raglan discovered the deep inlet of Balaclava harbour, a pretty little watering-place on the south coast and about eight miles in a direct line from Sebastopol. This was to be his base, he announced.

He could hardly have made a worse choice. For one thing, its prettiness was purely superficial. Behind its façade of trim little holiday villas, it was squalid and unsanitary, inhabited mainly by Greeks, who were hostile from the start.

Yet Balaclava was not only the sole base but the lifeline of the British Army, encamped on the heights six miles away in front of Sebastopol.

To guard that vital base Raglan had left only the 93rd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, under Sir Colin Campbell, 100 invalids and 1,000 Turks.

But two miles away, at the foot of the heights, the cavalry was in camp.

And it was this road that the Russians – stumbling on it by accident on the morning of October 25 – were fated to cut.

The Russians – two great columns of infantry and cavalry with artillery, 11,000 men and 28 guns in all – moving up to relieve Sebastopol, crossed the Vorontsov ridge, which split the valleys between like a camel’s back, cleared it and rolled down into the plain of Balaclava.

In the plain itself stood the two brigades of British cavalry, the Heavy and the Light. But they did not move. Lucan had his orders.

As he read them, he was to advance only when supported by infantry. And the 1st and 4th Divisions – which included the 63rd (Manchesters) and the 20th (Lancashire Fusiliers) were still two hours away, marching slowly and, as usual, in the wrong direction.

Nor could Colin Campbell help. Raglan had been implicit about that, too. Highlanders and cavalry must be kept for the defence of Balaclava.

So the unhappy Turks, serving the batteries on the Causeway Heights, were left to fight it out alone.

Under the concentrated fire of 30 Russian guns their defence wilted. The grey-coated horde flooded across the ditch and over the parapet.

Through the chill mists of that Autumn morning the Turks could be seen tumbling helter-skelter downhill, never stopping until they reached Balaclava shouting the only English they knew: “Ship! Ship!”

Now at last it was the turn of the cavalry, fretting, furious with inaction.

Lucan, on the alert for once, unleashed his Heavy Brigade – 4th and 5th Dragoon Guards, 1st, 2nd and 6th Dragoons. Leading the charge were the Scots Greys and the Inniskillings, riding side by side as they had done at Waterloo.

They broke into the front of the Russian column with a shout, forcing their way into the heaving mass of Russian cavalry until they were wedged in so tight that there was hardly room for a man to swing a sword.

Charge of the heavy cavalry brigade, 25th Octr. 1854,

William Simpson – Public domain

“It was no more than a gulley scrimmage” to quote a trooper of the Greys.

Then on came the 4th Dragoon Guards, crashing into the right flank of the column. And at the same time the Royals, charging in on the right front, and the 5th Dragoons, cutting and slashing their furious way into the centre.

The shock of this combined attack broke the mass like a hammer biting into a block of ice. In less than eight minutes the Russians were split and routed.

Now, if ever, was Cardigan’s chance. His Light Brigade was drawn up only 500 yards from the Russian right flank.

His lighter equipped Dragoons and Hussars could have gone through the ragged gap like wind after rain.

But Cardigan, too, had his orders. He was to defend his position, and he was obeying those orders to the letter. He sat glumly on his horse, watching the enemy in retreat.

“Damn those Heavies,” he was heard to mutter, over and over again. “Damn those Heavies!”

Next Episode: The glorious, disastrous Charge of the Light Brigade

Text:

The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

The British Library Board

© Reach PLC

© Jerry F 2021