Last time on Mystery Album we discovered that our mystery family were enjoying a fishing holiday at the village of Gunnersdale’s Kings Arms hostelry in Swaledale. Given the state of the dry stone walls and the mole infested riverbanks, we also wondered who on earth was in charge of the place. But before we explore that, let’s take a look at some more hundred-year-old photographs.

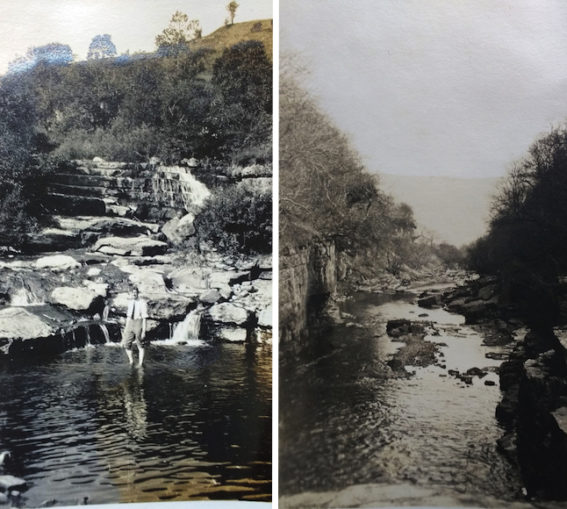

To the left, East Gill is pictured where it joins the River Swale partway down a succession of falls known as Keasdon (or Kidsdon) foss (or force), close to the village of Keld. An idea of the height of the falls can be gauged as a member of our mystery party is paddling in the middle distance. Pictured on the right-hand side is a classic view of Swaledale taken to the south of East Gill beyond a bend in the river.

Further up the valley, the building on the right with a stone-built lean-to on its northern side, catches the eye. It can still be seen on Street View from the B6270.

The photographer is standing on the dry river bed amongst a series of falls called Wain Wath Force.

These days the building is split into a number of dwellings and called Bridge End, with the actual bridge being visible to the left. In the intervening century, this has been replaced with a metal and concrete structure visible from the B road.

The other buildings in the distance are also still in situ. As the river takes a twist, despite appearances, all are on the same side of the Swale as Bridge End. The outhouse, which from the camera angle appears to be sitting on the bridge, these days has a corrugated extension facing the photographer. The land between that and the river crossing is covered by the Yurts of the Swaledale Yurts Park House, Keld, Bunkbarn.

The bridge is called ‘Park Bridge’. After crossing the River Swale, an unfenced road runs up West Stonesdale alongside Stonesdale Beck eventually following Startindale Gill to a high moor dotted with abandoned pits and mine shafts. An interesting three and a half miles from Park Bridge, the road reaches a junction at Tan Hill, home of the Tan Hill Inn – the highest hostelry in England.

As an aside, I’m a great believer that Cumbria is the greatest place on earth and it’s pointless going anywhere else unless you fancy a disappointment, but isn’t Swaledale interesting? Having said that, my maps are so old Cumbria isn’t on them. Not only that, magnetic north has moved. This doesn’t help when I’m out and about, but does serve as a useful scapegoat when companions realise I’ve managed to get us lost again. Therefore, there is a half chance that this far up the dale we might be in Cumbria anyway.

Then again, we might not.

Looking at the photo again we can see a couple on the river bank on the left-hand side and it is also notable the photographer is standing amongst a stony dry section of Wath Force.

In the next photo, we are hovering over the wet stuff which suggests the photographer to be standing on a bridge. Sure enough, the wooded scar on the right matches with the next photograph which also shows the bridge.

Note the serrated stonework which makes this bridge easy to locate on Street View and from there to find on the appropriate Ordnance Survey map. At first glance, this appears to lead to nowhere but on the other side, and slightly up the hill, are buildings mapped as Smithy Holme.

Also marked by the OS is Brian Cave. In his 1866 autobiographical work The Life and Labours of The Rev James Wilkinson, the author, a pastor of Keld and Thwaite and founder of the Keld Mutual Intellectual Improvement Society, describes this particular part of Swaledale by quoting a previous travelogue by a Mr Cooke. Despite a text full of mistakes and covered in annotations, we will quote the Reverend Wilkinson and Mr Cooke all the same.

“A little below this bridge is Whitsondale, and the rivulet which runs through it here falls into the Swale. In Whitsondale, which stretched about six miles to the north-west, there are, it is said, some very extensive caverns, and particularly one called Brian’s Cave.”

Your humble author tried to take an interest in Swaledale caving but talk of ‘Fat Man’s Agony’ and ‘Crackpot Cave’ dimmed his enthusiasm. Upon hearing mention of ‘Fairy Hole’, he made an excuse and left.

Back on the surface and starting from the bridge, if you’re a sheep or not frightened of clart, you can walk the eastern side of Whitsundale Beck to Raven Seat farm. Although marked as a right of way and footpath, from a distance this appears no more than a sheep run.

The road proper to Raven Seat is a mile along the B6270, further into upper Swaledale opposite where Birkdale Beck and Great Sleddale Beck join and, in doing so, form the River Swale.

Raven Seat is famous as the home of the Yorkshire shepherdess Amanda Owen of the Channel 5 TV series Our Yorkshire Farm and is part of the same country estate as the village of Gunnerside over seven miles down the valley. In all, the Gunnerside Estate covers 30,000 acres. In the 1920s, the dry stone walls were being neglected and the moles allowed to run riot under the ownership of the Peel family, descendants of Sir Robert Peel, Conservative statesman, Home Secretary, twice Prime Minister and founder of the Metropolitan Police.

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Bt by Henry William Pickersgill,

Henry William Pickersgill – Licence Public domain

Aerial photographs show the moorland for miles around being farmed for game.

Then and now, Gunnerside estate’s reputation was as the Holy Grail of grouse with, between the wars, a who’s who of establishment figures enjoying country sport there while staying at the impressive Gunnerside Lodge. Those visitors included Sir Charles Jocelyn Hambro, scion of the Hambro banking family.

As a young man, Old Etonian Sir Charles passed out from Sandhurst, joined the Coldstream Guards and served on the Western Front during World War One. He was awarded the Military Cross for conspicuous bravery in action. At the end of the conflict, he resigned his commission and commenced a career in banking.

At the outbreak of World War Two, Hambro found himself in charge of the Scandanavian section of the Special Operations Executive, tasked with making life difficult for the enemy in the German-occupied far north of Europe.

Recalling happier times on the moors above the Kings Arms and Raven Seat, he named one of his operations ‘Grouse’ and another ‘Gunnerside’.

An SOE objective in Scandanavia was to disrupt the production of heavy water at the Vemork hydroelectric plant at Telemark in Norway. Heavy water is used to moderate nuclear reactions and as such is required for the development of an atomic bomb.

Bildet er hentet fra Nasjonalbibliotekets bildesamling.,

Unknown photographer – Licence Public domain

Operation Grouse involved Norwegian commandoes, trained in Britain, being parachuted back into Norway. On 18th October 1942, they were dropped into the winter wilderness of Ejarifet and spent the next fifteen days skiing to Mosvatn from where they made preparations for glider landings which would bring a demolition squad from Britain to attack the heavy water plant.

On the 19th November 1942, two glider combinations (each consisting of a Halifax towing a glider) set off from RAF Skitten in Scotland carrying the demolition parties. The first combination struggled with poor weather and poor communications. The tow rope snapped and the glider only just made land. It crashed near Fylesda with three of those aboard killed and the others captured by the SS. The tow aircraft made it back to Scotland.

The second combination fared worse. The glider was released as planned but crash-landed between Helleland and Bjerkriem. Three were killed with the others taken prisoner and subsequently executed by the Germans. The towing plane came down in bad weather near Hestadfjell with all on board being lost.

With the Norwegian commandoes still in place, another attempt was made in February 1943, this time with the demolition party being delivered by parachute in what was named operation ‘Gunnerside’. The hydro plant was subsequently successfully degraded in an attack immortalised in the 1965 Anthony Mann film, “Heroes of Telemark.”

What does Mystery Album hold for us next time? If a friend tells you it involves a Cook’s tour of European nobility which bizarrely ends at this author, I couldn’t possibly comment.

© Text and photographs (unless otherwise captioned) Always Worth Saying 2021