Dear Readers, I plan to leave Alchemi in Stornaway for the duration of this article and take you on another trip in the Time Machine. Those who join me will flit forwards over the next 18 years with brief touchdowns in 2005 – 2007 and 2014-15 before flying back several centuries and landing for a short time in SE Asia and elsewhere.

I can offer this flight because I learned so much about coastal sailing in 1997 (and ocean sailing the following year) that I was able to leave behind the novelty and innocence of those years and carry on with my sailing life until beginning to lose interest and becoming too old to continue.

Before we take off though I’d like to thank folk who commented on my last article for their continued interest. Ever-vigilant Foxoles spotted a mistake that had escaped my own proof-reading. Foxy is quite right – settlement at Jarlshof has been traced to a period about 1,200 years before the start of the Iron Age around 1,300 BC and my words tripped over themselves when trying to distinguish between the two. I’d also like to clarify that the Brochs weren’t built until much later – a few hundred years either side of the Birth of Christ at a time when many people were still masters of working with dry stones.

Foxoles later comment included a beautiful photo of another Broch on the Scottish mainland that I took to be somewhere in the north-west from the landscape of low hills and lochs in parallel rows typical of those created at the end of the last ice-age. Reggie and pablo.umbongo liked it too though the latter thought it would look even better when the Broch was finished! Such comments are one of the reasons I enjoy GP.

I felt a little embarassed when reading Mrs Raft’s comment but was very pleased at the same time that I’d been able to communicate some of my own sense of wonder about parts of the world that I’d never have visited if I hadn’t taken up sailing. I hope my mother felt the same way because my original journals were primarily intended for her in the few remaining years she had left after my father died. I continued them until 2015 in the hope my own grandchildren would be interested, and in later years to pass on some of the knowledge gained to other cruising yachtsmen and women.

OK – please fasten your seat-belts and prepare for lift-off.

ALCHEMI’S VOYAGES IN SE ASIA

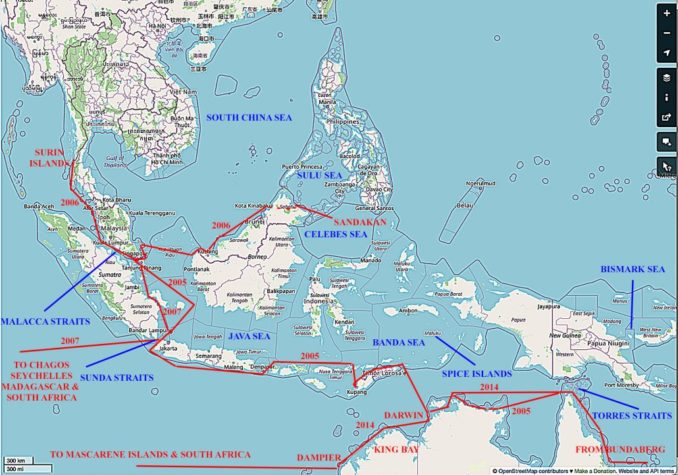

Here is a map of my meanderings in SE Asia and Northern Australia –

Alchemi arrived in Singapore from Australia in 2005 via the Sunda Straits and left the same way in 2007 after using Singapore and nearby Port Dickson as bases for two voyages in 2006.

The first was up the Malacca Straits and the Thai coast as far as the Surin Islands, 15 miles south of the border with Burma, and back again. I didn’t continue into Burma itself because of time constraints and the authorities’ price of US$1,000 per month for a cruising permit.

The second was to Kota Kinabalu in North East Borneo, again returning to Singapore. I didn’t try to sail to the Sulu or Celebes seas, partly because of the time required and partly because both had a reputation for opportunistic pirate attacks on cruising yachts by local fishermen. I rented a car instead and crossed the north eastern tip of the island, past 13,455 feet high Mount Kinabalu to Sandakan, to see the countryside, the sea from the coast, and to stay at a primitive Jungle Camp where we fought off insects, shooed-away marauding macaque monkeys, saw many birds, and had a few glimpses through foliage of wild orangutan (in the malay language orang = person and hutan = forest).

The only overnight passages needed during these voyages were those between Singapore and Borneo and one half way up the Bornean coast when a sudden windshift converted a protected anchorage into one exposed to onshore winds in shallow water.

There were many places in the region I didn’t visit but I found the ones I did go to were fascinating and maybe I’ll be able to tell you more about them another time. For now, I just want to set the piratical scene in its historical context.

GENERAL HISTORIC BACKGROUND

Australian Aboriginees, Melanesians and Polynesians are all thought to be descendants of the original peoples of this region. Much later, those who remained were influenced by immigration and cultures from other parts of the world and the whole region has seen a succession of struggles for supremacy between peoples from many countries.

In the west and south, Indian influence began about 300 BC, that from the Middle East around 1100 -1300 AD with the Europeans, Chinese, Japanese and Americans being johnny-come-lately arrivals, mainly between 1511 and 1900 AD. We westerners naturally know more about events after arrival of the Portuguese and Spanish, if only because European sources are so much more accessible to us than Asian ones.

The Portuguese, coming from the west, established an enclave at Malacca in 1511 and the Spanish, coming from the east and led by the Portuguese navigator Magellan landed in the Phillipines in 1521. The Dutch arrived about 100 years after the Portuguese and Spanish and were in turn followed by the British and French some 200 years later still. The Chinese appeared in the north in the late 1600’s and the Japanese about 150 years after that. The Americans joined in during the last two years of the 19th Century and have been playing a major role ever since. Perhaps wisely, the Russians only sought to influence events indirectly and although the Cubans were active in Africa they don’t seem to have become involved in SE Asia. The South Americans were too busy with their own affairs.

In addition to their possession at Malacca the Portuguese succeeded in colonising the Eastern half of Timor Island and the Macau enclave in Mainland China.

The Dutch established their SE Asia power base in 1619 by defeating locals on Java and capturing a city they renamed Batavia (now known as Jakarta). Three years later they founded a colony on an island between mainland China and the Phillipines called “Beautiful Island” by Portuguese sailors who didn’t attempt to colonise it – (Formosa). In the same few years the Dutch established control over the Spice Islands (Malukas or Moluccas) ejecting the Portuguese who were the first Europeans there and fighting off the Spanish and the British. In 1641 they captured Malacca from the Portuguese. Later they expanded until they controlled most of modern Indonesia including West Timor and Sumatra.

The Spanish power base in SE Asia was at a city called “New Castille” (later known as Manila) on the island of Luzon in the Phillipines named after Phillip II of Spain, the Great Grandson of Isabella and Ferdinand whom readers may recall were the Joint Monarchs who expelled the Moors from Southern Spain. The Spanish had a great deal of trouble from pirates in their new colony (both locals and from other countries) and that hampered their efforts to expand their territory in the Spice Islands and on Formosa. They lost out to the Dutch in both cases.

When they arrived in the region the British founded the modern cities of Penang and Singapore on islands just a stone’s throw from the Malaysian Mainland and soon afterwards swapped territory on Sumatra for Malacca thus consolidating their position in Malaya and the Dutch one in Sumatra.

One notable difference in approach between the Northern and Southern European countries was that the Portuguese and Spanish were mostly State Controlled whilst the British and Dutch efforts were conducted by their privately-owned “East India Companies” that were nevertheless permitted to organise Private Armies and Navies!

The economic driving force for all the European countries was the acquisition of raw materials and the sale of their finished goods at prices favourable to them.

The British East India Company’s policy was generally to keep Colonial Government Taxes and Duties on Imports and Exports as low as possible and to allow traders from other nations open access to their markets. In modern business school parlance they were trying to drive down purchase prices for raw materials and increase the volume of finished goods. In contrast the other countries operated systems of monopoly rights with market access restricted to their own nationals. Business School parlance for them would be adoption of a high margin strategy supported by legal restriction of competition.

There are some fun stories associated with these difference that I may have time to relate in a later article. For now I merely remark that I don’t think the the effects of the different policies on theft and piracy were always fully considered. Of course, a thief or pirate will always benefit from the price he can get for stolen goods. But if he can sell them in a market where prices are higher because of a monopolists higher margins or a source Governments higher taxes he will gain extra by stealing some of the additional mark-up as well as the intrinsic value of the goods.

Arguments for and against “Free Trade” and “Domestic Protection” policies have been going on for a very long time. They continue in the present day of course with considerable resources being devoted to “Trade Neogotiations” in which the parties try to agree how many of their own legal restrictions they are prepared to lift in exchange for the other party doing likewise.

Trade Agreements probably matter less these days because many more Governments now practice High Tax and Spend policies and impose fewer restraints on Monopolistic behaviour by both State and Private Organisations. Those policies tend to increase consumer prices and create a “Black Market” as modern day pirates and other criminals try to gain for themselves some of the extra margin, just as their predecessors did in earlier centuries. The same sort of piratical and emotive language is still used in an attempt to persuade entire populations of the wisdom of their own Government’s stance. Free Marketeers are derided as “Freebooters” and those in favour of high taxes and other forms of protection are accused of creating “Red Tape”.

The only aspect of this relevant to my own experience whilst still working and when sailing after retirement is that Legislation and Regulation also provides individual officials with what a colleague of mine used to describe as “Earning Opportunities”. They go something like this – “What you are doing/proposing is or may not be compliant with Law XYZ but perhaps I could help you by interpreting the requirement in a way that would allow you to go ahead if you could help me in some way ….”.

That will do for now because that is the stuff of modern politics and I wish to leave those behind and go on to more particular stories about the past.

WILLIAM DAMPIER AND COLLEAGUES

I’d like to tell you now about one particular English Pirate and his exploits in this region and others around the world and hope that although the story may be known already to some that it will be new to others.

To introduce him I revert to the map showing my own voyages. You’ll see that after being in SE Asia in 2005-7 I continued to South Africa via the Northern Indian Ocean and directly from Australia the second time around in 2014. In that year, starting from Bundaberg just north of Brisbane I sailed to Dampier in Western Australia via Darwin before going on to Rodriguez, Mauritius and Reunion on the way to Richards Bay in South Africa for the second time.

[To round out the biographical picture I add the following – On the second occasion in South Africa and after a tough arrival I felt relatively uninterested in repeating the 8,000 mile voyage I’d made in 2008/9 to the Caribbean (and then what?). Nor was I keen to try drifting my way back to Europe through the Doldrums and calms of the Azores High Pressure System worrying all the time whether I’d run out of fuel and water. In any case, I’d already visited all the Azores Islands in 1998 – the year I first ventured on Ocean sailing – and what new and interesting thing could I find to do if I did arrive in Europe that was cold and wet for 6 months of the year? Going north wasn’t attractive because the Somali Pirates were on a roll at the time and that was a major deterrent to going to Tanzania that I would otherwise have liked to see. Thinking I was getting on a bit anyway as I was in my 79th year, and still wanting to do something else with the rest of my life, I decided to end my sailing career and sell Alchemi at much less than her true market value practically anywhere else in the world]

Like me, the English Pirate William Dampier was a Somerset man (well, I was born in Bristol but only lived there for three years before my parents moved into the countryside to avoid German Visitors in the Sky). William was an amazing man. You can read more about him at several websites but here is a copy of the first two sentences from Wikipedia –

William Dampier (baptised 5 September 1651;[1] died March 1715) was an English explorer, pirate,[2] privateer, navigator, and naturalist who became the first Englishman to explore parts of what is today Australia, and the first person to circumnavigate the world three times. He has also been described as Australia’s first natural historian,[3] as well as one of the most important British explorers of the period between Francis Drake 16th century) and James Cook (18th century), he “bridged those two eras” with a mix of piratical derring-do of the former and scientific inquiry of the latter.[4]

The Wikipedia entries under the heading “Legacy” are fascinating and illustrate how many better-known names in many fields were influenced by Dampier’s findings and accomplishments from the first known use in English of the word Avocado through the first known description of the Breadfruit plant to the first compilation of ocean current data later used by Cook, Nelson, Humboldt, and others. But I found the Wikipedia entry rather disjointed and hard to follow. After poring over it and other websites I have compiled the narrative that follows. One of the best sites I found is this one from the National Museum Australia which has coherent text and some great pictures. Another important source for the last period in Dampier’s life is a book by modern author Robert Fowke that is a great read with far more detail about the voyages off South America and the literary connections than my highly condensed summary below.

EARLY YEARS – 1651 TO 1687

Dampier was born in 1651 and joined the Navy in his early 20’s. He had to leave due to ill health from which he did not fully recover until 1679 when he signed on to a pirate ship operating in the Caribbean and on the Spanish Main (mainland colonies in Central and Southern America). He spent several years raiding in those regions before crossing the Pacific in 1686 to do the same in SE Asia. His early targets were in Spain’s Phillipine colony but he also went south into the Banda Sea and around the Spice Islands (now the Maluku archipelago) so named because Nutmegs, Cloves and Pepper grew there in great abundance.

Control over these islands had been contested for many years because European demand for the spices was insatiable and they were worth their weight in gold. The Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish and British were the main contenders and the Dutch had come out on top a few decades before Dampier arrived.

IN AND NEAR AUSTRALIA – 1688 and 1699

After leaving SE Asia on “Cygnet” Dampier ended up in early 1688 near King Bay on the North West Coast of Australia where the ship was beached for careening (Alchemi stayed there too in 2014 but not for careening – her anti-fouling paint worked for longer than Cygnet’s). The crew were the first English people to set foot in Australia and the ship stayed there for two months whilst she was being scraped and repaired. During that time Dampier, motivated by his normal curiosity and industry, made notes about the local inhabitants, the plants and the creatures found there.

When he returned to England, Dampier wrote a book about his adventures called “A new voyage around the world” that became very popular.

Jonathan Swift was familiar with this book and probably drew some materials from it for Gulliver’s Travels in which he compares his fictional hero’s exploits with William Dampier’s real ones.

The book also impressed the Admiralty and that resulted in Dampier rejoining the Navy. He was appointed commander of a small ship called the “Roebuck” and commissioned to explore the East Coast of Australia. She didn’t leave England soon enough to get round Cape Horn before winter and so sailed East round South Africa and approached Australia’s West rather than East Coast. Roebuck made landfall at a large indentation in the coast that Dampier called Shark Bay some 700 miles south west of King Bay where he had landed 11 years earlier. During his time in this area Dampier conducted his normal studies of plants, animals and people and also charted the coast for some 200 miles to the north where the port named after him is now situated.

Still trying to fulfil his commission Dampier sailed north to Timor, across the Banda Sea and north of Papua New Guinea before turning south towards Australia and the Eastern end of the straits found by Luis Torres 93 years earlier. Dampier made his usual notes and charts of the coast and islands off Papua New Guinea in what are now called the Bismark Sea and Straits but turned back about 100 miles north of Australia because the Roebuck was becoming unseaworthy. That left the East Coast unexplored by Europeans until James Cook arrived in Botany Bay some 70 years later.

IN SOUTH AMERICA – 1703 AND LATER

When he returned to England, Dampier was dismissed from the Navy after a court martial found him guilty of abusing his lieutenant on the Roebuck who had complained to the Admiralty. William was soon back at sea again though, resuming his old trade of Pirate and Privateer. He was the senior commander of a two-ship expedition off the coast of Chile in 1704. His ship was the “St George” and his Junior’s the “Cinque Ports”. I use the words “Senior” and “Junior” only to indicate Dampier was the older and more experienced man on the larger ship. At the time the the Cinque Ports was commanded by a young man called Stradling who had taken over when her original captain died on the voyage from Kinsale. There was no formal command structure as there would have been if they were Naval Officers.

The two ships parted company in May of that year and soon after, Stradling rid himself of the troublesome Scots crewman Alexander Selkirk by marooning him on the uninhabited island of Mas a Tierra. One of Selkirk’s complaints had been the ship was unsafe and should be repaired before further use – he was right, the ship sank not long afterwards. Over four years later Dampier was again at Mas a Tierra as Pilot on the “Duke”, another privateer sailing in company with the “Duchess”. They found and rescued Selkirk who was still alive and sane and remained on the “Duke” as a crew member.

Selkirk’s experience is widely believed to have influenced, or possibly even been a model for Defoe’s story about Robinson Crusoe sometimes called the first English novel. The connection is not proven beyond doubt because there are significant differences – Crusoe is marooned for 28 years not four and the island in Defoe’s tale is tropical and Mas a Tierra certainly is not. Literary niceties haven’t bothered Tour Companies, Wikipedia and some map-makers though and many of them now use the name “Robinson Crusoe Island”.

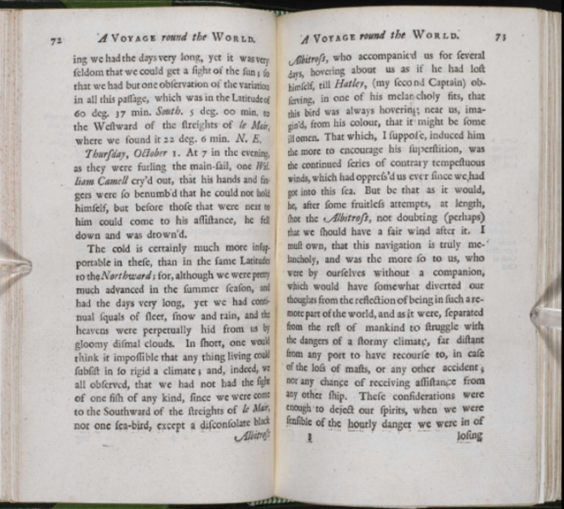

There was a third pirate in the two-ship fleet at the same time as Dampier and Selkirk. His name was Simon Hatley and Robert Fowke has shown he was the same man, born in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, who was later captured and tortured by the Spanish in Peru. After being released by the Spanish and returning to England Hatley signed-on for another voyage on a boat called the “Speedwell” captained by one George Shelvocke. Shelvocke wrote a book about the Speedwell’s voyage in which he recorded that a seaman called Hatley had shot an albatross during a storm whilst rounding Cape Horn.

Seventy years or so after Shelvocke wrote his book William Wordworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge discussed the story during a walk on the Quantock Hills in Somerset and Coleridge used the albatross incident at Wordsworth’s suggestion in his famous poem.

Dampier, Selkirk and Hatley sailed together in 1709 and respectively inspired or were at the very least influential in the creation of those three great works of English Literature – Gulliver’s Travels, Robinson Crusoe and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. I hope you find that story of an early link between Piracy and English Literature as fascinating as I do.

POSTSCRIPT

Interestingly, Hatley shot the albatross in latitude 60o 37 ‘ S just 3 miles farther away from the South Pole than Alchemi was relative to the North Pole when circumnavigating Shetland. Shelvocke also records on page 72 that William Camell fell out of the rigging and drowned because his hands and fingers were too numb to hold on any longer. He also remarks how much colder it is near the South Pole than the one in the North even in mid-summer.

Perhaps he’d sailed round Shetland and benefited from the Gulf Stream as I did. I’ve estimated from average temperature data for January and July respectively that the mid-summer difference is about 12 o C but Camell would have felt a good bit colder because he was exposed to gale force winds, rain and sleet whilst being swayed hither and thither many feet up the mast and out along a spar whereas we had a calm and sunny day in a safe and dry cockpit.

There aren’t any albatross in the northern hemisphere and after seeing them nesting in New Zealand I wouldn’t have wanted to shoot one anyway. Here’s a pic from Creative Commons to replace a similar one of my own that I couldn’t find (The limit of this species range is about 40 o S and the word northern is used to distinguish it from the southern royal albatross whose habitat lies even closer to the pole).

To be continued …………….

© Ancient Mariner 2021