I start this article with a response to points raised or ideas triggered by comments on part 26, and as usual thank all those who made them. The continuing interest stimulates further effort to keep on refreshing distant memories and sharing them with others..

I enjoyed Bill Quango’s question – Are you hunting the Bismarck ? and Beri Cicikov’s response – Do you expect him to betray the official secrets’ act by answering that ? I can clarify what I think both of them knew perfectly well already. The answer to Bill’s question is – “No. I was merely seeking an interesting and adventurous route around the UK to confirm I’d made a good choice of lifestyle for my retirement years”.

K2FDETDFS said – “Ancient Mariner, would love to hear some more climbing stories”. I have already included one digression on Mountaineering in Part 17 of this series when I briefly described Bill Tilman’s transition from climbing in the Himalaya to Arctic and Antarctic mountains and how the Reverend Bob Shepton continued that tradition with both sailing their own yachts to reach the peaks that attracted them – “Because they were there!”) I include now the Video of the televised ascent of the “Old Man of Hoy” posted by Sharpie Type 301 in another comment on part 26 that K2….. may not have seen (I also thank Sharpie for posting it – I had looked but failed to find it myself). I feel very hesitant about attempting any more tales from my own young life because they would be totally insignificant in comparison. Anyway, I suspect K2…. may be an accomplished climber with more exciting tales to tell than I. K2 is after all the second highest mountain in the world and far more difficult to climb than Everest with a 25 % mortality rate amongst those who make the attempt. I’ll think about it some more because one or two of my experiences may be of some interest to those amongst my grandchildren who are following this series and are now the same age that I was myself when a member of my University Climbing Club.

DJM’S comment confirmed my expectation the PureBlood family or their prisoners are very well connected with one another (am I missing something here – where does the PureBlood name originate?). I met some-one in South Africa who told me we were “Kindred Spirits” even though there were many years difference between our respective ages. I think DJM and I are similarly positioned. I was also pleased to learn of the precautions he and La DJM take after only a few days at sea, and that WATTYLERS WIFE and Watt himself feel a similar need from time-to-time even though they don’t put to sea at all.

I was sorry to learn Foxy broke up with a boy-friend after she knitted him a Fair Isle jumper and hope the jumper wasn’t the cause of their problem. You didn’t insert a Purl stitch where it should have been a Plain one did you?

I was very interested to learn COMMERVANMAN is currently based in Hong Kong and owns a 40 foot keel sketch out there. I never did sail in the area though I used sometimes to be taken as a guest on a double-decked Sport’s Craft with a huge twin-engine that zoomed out from Kowloon to Lamma Island and beyond in the late 1970’s. I was also a frequent visitor in the early 1990’s when seeking new business in Mainland China and Taiwan (not on the same trips – that would have been indelicate). Having thus experienced the choppy waters in Victoria Harbour and the Pearl River Estuary I would be interested to learn more about what it’s like to sail from Hong Kong as a base. How about writing an article to tell us Commervanman?

ALCHEMI’S 1997 VOYAGE

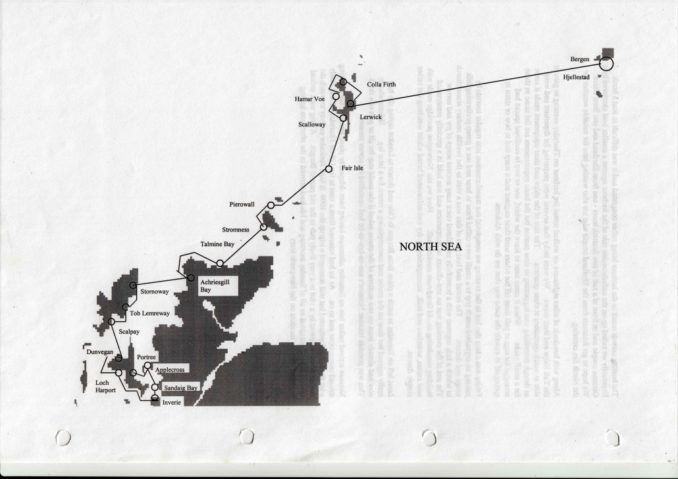

Here again is the planning map for this leg of the voyage to remind readers we last left Alchemi in Stromness harbour in Orkney during August.

The strait between Orkney and the Scottish mainland is called the Pentland Firth and is an area of very strong tides.

The west to east tidal currents are created when sea level in the Atlantic Ocean rises as it is attracted towards the moon and water rushes into the North Sea from the Ocean. The exact timing varies but broadly speaking that happens twice a day as the moon reaches its highest position as seen by an observer on earth and 12 hours later as the earth rotates through 180 degrees. The reverse happens 6 and 18 hours after the first high tide when the currents flow from east to west as the water rushes back into the Ocean from the North Sea.

A fuller explanation of tides and what causes them is much more complex because the moon’s gravitational pull on the earth is the dominant but not the only cause of their existence. Incidentally, land masses have tides in their position too but the movement is much less noticeable as rock and earth don’t flow nearly as readily as water. Changes in land height by as much as 56 cm have been observed though and that’s important for some activities as described on this National Geographic website

Currents are highest at the eastern end of the Pentland Firth where the strait is narrowest but can still be a serious thing to consider until well west of Stromness. Farther west still they are not so serious when well away from coasts but do assume importance if near the mainland at Cape Wrath. There, as with all places where there’s a sharp change in coastal direction, caution is necessary because there is sure to be an area of accelerated flow as water finds its way around the obstruction. The shape of the seabed also has an important effect on water behaviour at the surface. Places where the seabed is flat in all directions are relatively few. In others where there are significant hills, valleys and sometimes individual pinnacles, the fast-moving water flowing past and over it can get turned into a very turbulent heaving mass or whirlpool on the surface.

A mariner in these waters needs to pay close attention to all these effects as the visitmyharbour.com website makes clear. Here’s a general warning from the site:

“ With smooth water and a commanding breeze, the firth is divested of its dangers, but when a swell is opposed to the tidal stream, a sea is raised which can scarcely be imagined by those who have never experienced it; and, if, at the same time, the wind is light and with the stream, a sailing vessel becomes unmanageable.”

The image of a small sailing yacht driven by a strong wind battling up a steep and breaking wave driven in the opposite direction by a 12 knot tide is easily imagined. The opposite condition of the same small yacht in a light wind being carried forward by a 12 knot tide in the same direction is less easily visualised by those who have never sailed in one. Those who have can pass over the next three paragraphs but for others I need to explain –

The direction in which a sailing vessel is pointing can be controlled to some degree by adjustment of the sails. The wind pressure upon them creates a sideways force as well as one drawing or pushing the hull forward. In common breezes and reasonably calm waters the sideways forces on the sails can be balanced against one another and by opposing forces produced by water pressure on the hull that resist any tendency of the yacht to turn off-line. Under such conditions the direction in which the yacht is moving can sometimes be controlled by adjusting the area of one sail or the other and how far from the centre-line of the yacht they are allowed or required to go.

Under most conditions however, waves or variable wind direction make that very difficult or impossible to achieve. That’s when it’s necessary to call upon a steering oar or rudder. These work by increasing water pressure on one of their sides through which it can be used to create a sideways force on the hull from the oar’s rowlock or the rudder’s stock. Since they are usually mounted at the stern of a yacht there is a long lever-arm to the hull’s midships and the yacht changes direction until a new balance of forces exists. The helmsman controls that by adjusting the angle of the oar or rudder until the yacht is moving in the direction the navigator desires and though the yacht will be slowed down by the backwards force created by water piling up in front of the oar/rudder, those on the sails will usually be sufficient to keep the hull moving forward.

If the wind is very light and a water current in the same direction is very strong, the water will be moving faster than the yacht floating upon it. That will be equivalent to the boat trying to sail backwards over the water instead of forwards. In Alchemi’s case a 12 knot tidal flow would convert her best speed forward through the water of 6 knots into one that felt as though she was trying to reverse at 6 knots with the sails still full of wind. That would be very difficult to do and the slightest disturbance would convert her from a Forward Facing Torpedo into a Pooh-Stick turning hither and thither in a fast-moving stream. That is what the “visitmyharbour” website means when its author writes “a yacht becomes unmanageable”.

The site goes on with its description in these terms –

“Before entering the Pentland firth, all vessels should be prepared to batten down, and the hatches of small vessels ought to be secured even in the finest weather, as the transition from smooth water to a broken sea is so sudden.

The change from light winds to a strong breeze which occurs when passing from an eddy into the stream, and vice versa, is rapid, so that too much sail must not be carried. So distinct is the line of demarcation between the stream and the eddy that, in passing from one into the other, the largest vessel may be twisted round with considerable velocity.”

I don’t think the “visitmyharbour” site was available in 1997 but you can be sure that as a relatively novice yachtsman I had scoured all available sources of information about the passages I was hoping to make before embarking on each leg of the voyage. Naturally you don’t get 12 knot tides in all sections of the Pentland Firth and they are slower where the firth is wider at the Western end but still fast enough to be treated very respectfully.

In the event, any worries about meeting a “Sabre-toothed Tiger” set of conditions turned out to be totally ill-founded because the ones we actually experienced were more at the “Pussy Cat” end of the spectrum. Here is an extract from my journal written at the time.

Departure from Stromness Harbour at the turn of the tide saw us motoring down Hoy Sound into a light north westerly breeze just at the start of the ebb tide. Even in these mild conditions the waves became noticeably steeper as the remains of Atlantic rollers met the outgoing stream, a pointer to the rough conditions to be expected in more severe weather.

Before leaving we had of course checked the weather forecast and realised a low pressure system in the Atlantic had been moving towards the British Isles. We had also assessed the distance around the mainland before a protected anchorage could be reached and realised doing that couldn’t be achieved in a single day. My journal continues –

The wind returned more strongly just before 18:00 and although it was entirely manageable we decided to head for the Kyle of Tongue for the night. After a rather over-tentative approach we safely passed Rabbit Island and the rocks opposite to enter Talmine Bay and drop anchor in 8 metres not far from two other yachts, some local fishing boats and a rather unwelcome collection of fishing floats.

The night passed peacefully and we were up at 08:00 the following morning in time to catch the west-going tide. The wind had veered through 120 degrees overnight so we set the main and poled out the jib to sail west at just under 4 knots in an 8 knot breeze.

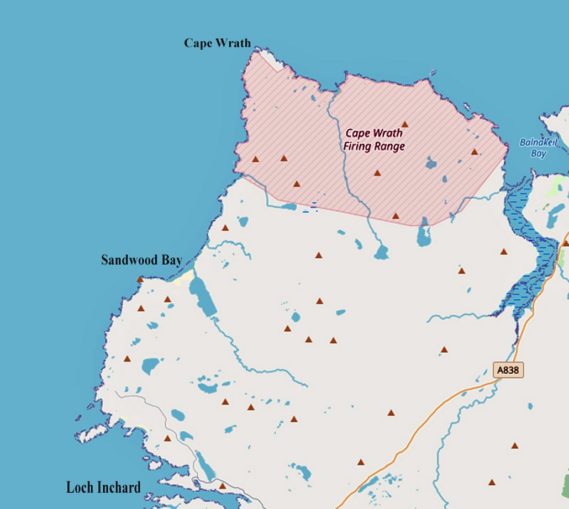

The sea was calm, the day sunny, the sail soothing and we wondered at the tales of mighty winds as we glided past Cape Wrath.

Here’s a view of the Cape that will be more familiar to those who have visited by land.

A superficial look at a general map of NW Scotland creates the impression Sandwood Bay, about 6 miles south of Cape Wrath on the mainland, would be well protected from waves and an attractive place for a small yacht to anchor.

That’s one of the best examples I’ve come across illustrating why mariners must use proper marine charts when planning and undertaking their voyages. The false impression of a suitable anchorage is continued in the modern age on both OpenStreetMap and Google Maps if looked at in map view. But when the same area is studied in Google’s Satellite view it will be seen there is no navigable entrance and a run-off stream emerging from the loch disappears at the landward edge of the beach before water reaches the sea by trickling through the sands well below their surface. That would also be shown clearly on a marine chart.

I mention this because I have referred before to my use of Google Maps to record anchorage positions around the world. I haven’t reproduced any of them in these articles for copyright reasons but if a reader comes across them elsewhere, or to similar use of Google Maps produced by other authors, they must always be used in satellite view when a good indication of physical topography is important (as it always is when sailing, cycling and walking).

Of course, Google Maps didn’t exist until 2004 when Google acquired a software company using a stand-alone C++ computer program written by two Danish brothers and I was using British Admiralty paper charts for navigation in 1997 and many years thereafter.

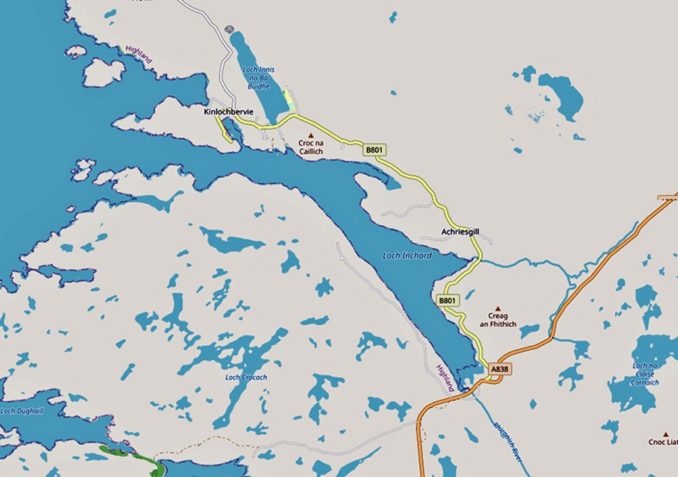

Once round the cape we changed the sail plan to Main and Cruising Chute and continued under light breezes from the east until 16 miles to the south we could turn into Loch Inchard past a sunken rock near the entrance.

The warnings in the Pilot Book about Loch Bervie’s unsuitability for yachts were fully vindicated by our own observations. Most of the harbour was devoted to commercial fishing and its support services and plentiful large signs warned that harbour dues would be levied for stays of any duration. One small pontoon for yachts mentioned in the Pilot was fully occupied by very small craft indeed, except for one space taken by – a commercial inshore fishing boat.

Deterred by all this we made our way 3 miles inland to Achriesgill Bay where we found anchorage in a small area within the space occupied by a proliferation of fish farms.

To be continued …………….

© Ancient Mariner 2021