I have seen SB’s notice he is running short of articles again and have difficulty doing what I promised last time because I’m still on my land voyage by caravan. I don’t have all my source materials with me to write about my first Ocean Voyage to the Azores Islands and am again going to postpone doing that by describing my current land voyage since leaving Devon, and thoughts associated with it.

SALISBURY AND NEARBY MONUMENTS

STONEHENGE

I start by saying I visited Stonehenge in my youth when it was still accessible by a bike ride through quiet country lanes and one could walk between the stones.

When I was in my late twenties, Gerald Hawkins, English-born professor of Astronomy at Boston University, wrote an article and book postulating the monument was an early form of astronomical observatory. He had deduced certain lines of sight between the inner ring of large stones and the outer one called the Sarsen stones could be used to predict the timing of eclipses as well as the winter and summer solstices. His work was endorsed in 1966 by Fred Hoyle from his prestigious position as Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge University.

Forewarning of those sorts of events was pretty useful information for farmers of the period particularly frightened by eclipses of the sun and welcoming information about when it would be best to sow and harvest their crops. Priests who could understand these messages from the gods were important people, rather like the present Government’s scientific advisors.

Hoyle was also the person who first used the term ‘Big Bang’ to describe a discontinuity in Time and Space now used very often in the sense of meaning the ‘Start of the Universe’ and of Life within it. Hoyle himself didn’t believe it was. He favoured instead the hypothesis of Panspermia first advanced by the Greek Philosopher Anaxagoras in the 5th Century BC.

Hoyle put forward some arguments for that in his book “The Intelligent Universe” (1 Mar 1988), a copy of which I still look at occasionally when I’m at home. His academic work on how new elements were created by high-temperature fusion reactions in stars strongly influenced his thoughts about how life could have started.

In his book he wrote about the formation of amino acids, proteins, DNA, RNA, Ribosomes, Genetic Codes and so on, and deduced life was most unlikely to have originated on earth. He argued it probably pre-existed but found the environment particularly beneficial for its survival and development when it got here, having taken a ride on a comet or another bit of rock arriving from elsewhere in the universe. (He was referring to those and not to the world’s first commercial jet that entered service in 1949).

Some still support the theory that ready-made life-forms hopped off a comet just before it landed or survived the impact. Others argue the intense temperatures created upon impact could have caused a fusion of the simple pre-existing elements oxygen, hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen, thus producing amino acids that are known to be mainly composed of those elements. Amino acids are also recognised to be the building blocks of proteins and other compounds found in all forms of life so far discovered by humans. Cosmologists and Astronomers wonder if earth was unique in the universe in having it’s particular combination of elements. Hence the search for earth-like planets in our own and distant galaxies.

All that seems to be certain is that no convincing theory about the origins of life on earth, supported by rigorously tested objective evidence, have yet been found. Plenty of examples of the obverse have been of course – from simple cavemen’s clubs to nuclear bombs and to biochemical weapons as well. Some people even worry about eating genetically modified crops but are at the same time reassured by the torrent of messages from the likes of Boris Johnson, Matt Hancock, Sajid Javid and their advisors, that mRNA vaccines against Covid-19 have been thoroughly tested and have only beneficial results. We are certainly more knowledgeable than the Ancient Brits but are we really any wiser than the leaders of society and their Druid priests of 5,000 years ago?

I doubt the impact of a Comet jet liner would have had sufficient mass to create high enough temperatures to cause such elemental changes. Three did crash into earth though in 1953 and 1954. The underlying cause of the crashes was found to be metal fatigue at the corners of its square windows.

A jet engine works by creating a forward thrust in its supporting structure by ejecting mass behind it, instead of using propellers to do the equivalent by pulling air in at the leading edge of its blades and pushing it backwards. An atmosphere is necessary for ‘planes with both types of engine to stop them from falling to the ground but a jet-engined one needs less as it goes faster. So, commercial jets are optimised to fly at 35,000 feet or thereabouts whereas piston-engined ones best altitude is about 20,000 feet. Passenger comfort requires the pressure differential between inside and outside the cabin to be much higher in jets than it is in propeller-driven ones.

The Comet’s fuselage, weakened by fatigue cracks around the windows due to high stress concentration factors there, failed in mid-flight because it could no longer contain the internal pressure and blew apart. That’s why all jet ‘planes with pressurised cabins nowadays have oval portholes. Production of the Comet continued until 1959 and I have found this BBC report showing a photo of the last square-windowed one to survive inside a new Hangar at the de Havilland Aircraft Museum in Hertfordshire. I think the museum is likely to still exist because Trip Advisor gave it a 2022 Traveller’s Trip Award. But, the museum’s own publicly available website still contains a 2018 video appealing for funds to build the hangar and doesn’t seem to include the Comet as one of its exhibits or aircraft in storage.

After that aeronautical digression I’d like to get back to the mystery of life’s origin and end. Startlingly, I was surfing the web for half an hour the other day before finishing this article and came across an analysis of the elemental composition of the human body showing 96% of our mass is composed of Oxygen, Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen (3% is mineral and 1% trace elements). Oxygen dominates with a little more than 61% and Carbon is next at about 23% of our mass.

I hope Boris Johnson’s plans to achieve Net Zero by 2050 don’t include killing us all off, though sometimes I do wonder! (On a personal note, my Will asks my Executors to dispose of my body as a “Natural Burial” in which my carbon will be recycled in the ground. I think that would be better socially than cremation which would add even more carbon to the atmosphere (its already about .03% of the total by mass). I reckon that’s a pretty important contribution I can make towards the avoidance of Global Warming but I’d like the timing to be deferred for a bit longer. I hope Boris is planning the same thing because he’s a bit overweight too).

I still prefer musing upon Hawkins’s and Hoyle’s ideas about Stonehenge to queuing for hours before marching around the monument at a distance, in company with strangers, and looking at the large stones through binoculars.

OLD SARUM

I wanted to see Old Sarum because my father and I, again in company with the Assistant Scout-Master and the boy with whom we tried to canoe from Bath to London that I mentioned in part 2, tried to walk here at Easter during another year in the late 1940’s or early 1950’s.

The expedition was inspired by trying to re-create the experience of early Britons who travelled about the country on foot at high level to avoid wild animals and hostile tribes living in the valleys below.

One such route ran from a Peninsula in the Severn Estuary called Brean Down near Weston-super-Mare where we lived, to Old Sarum which was a Hill Fort in the Iron Age before arrival of the Romans.

We didn’t make it, and only got as far as Charterhouse, high in the Mendips near the old lead mines started by the Brits, continued by the Romans and subsequent Invaders but abandoned in 1908 because it was cheaper to get better quality lead from other sources.

We awoke one morning, after a night of what we thought had been light rain, to find our tents had become igloos and we were in the middle of what looked like an arctic snowfield. End of expedition. I can’t criticise my dad and the Scoutmaster for lack of ambition but their plans didn’t always work out.

Anyway, this year, in the comfort of a modern car and caravan I did get to visit Old Sarum.

Here’s a photo of the outer earthworks from an attacker’s point of view (to be fair these are Norman earthworks). The ones created in the Iron Age would have been simpler – it would still have been a steep climb though. Of course, in Ancient Brits days the tourists visible at the top would not have been looking in the other direction. Instead they would have been shooting arrows at you, rolling large stones downhill, and firing small ones from slings whirled around their sides.

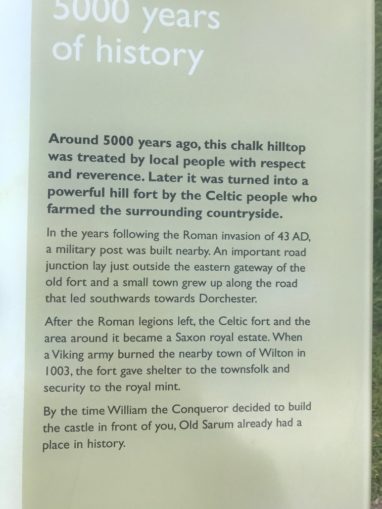

The site is now an historical attraction run by English Heritage, and to my surprise was an important centre for several civilisations after the Ancient Britons.

First came the Romans and then the Saxons and Vikings followed by the Normans. The remains still visible today are mostly from the Norman period.

There were helpful diagrams and notes on signs beside the approach path between the outer earthworks and the inner walls. I took a couple of photos of each showing diagrams and text separately so I could see them without straining my elderly eyes – I hope they do the same for you.

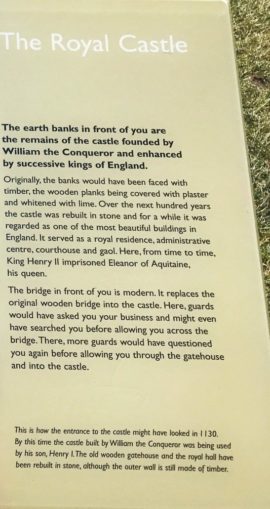

The second notice showed a visual recreation of the Norman Drawbridge across the Dry Moat, replaced today by a simple one in modern materials.

As always with these sorts of places there are fees to pay – for parking one’s car and for entering the inner castle.

I paid the former but entered the latter no further than the English Heritage shop. Inside, I bought a half-price jar of locally made jam after contemplating the astonishingly small pots of Dorset Ice-Cream and concluding they were too bad for my waistline and too expensive for my purse.

I was absolutely delighted though to see on the shelves paperback copies of a book I treasured in my youth. I used to tell stories from it by memory to my second oldest granddaughter when she was little. That was some 10-15 years ago and I ended up giving her a hard-back copy as a birthday present one year.

‘Our Island Story’ was written in 1905 by Henrietta Marshall. It is an account of the History of England from the Roman Occupation to the death of Queen Victoria. The style is simple and designed to both inform and entertain youngish children – it is indeed a storybook, but based on real events rather than fictional ones. I think my granddaughter found it nearly as appealing as I did, and there’s 64 years difference between our ages!

SALISBURY CATHEDRAL

I first saw the cathedral as a young boy on one of the bike-rides with my Dad. Even at that young age I was hugely impressed by it and particularly by the elegance of its Spire – I thought it the best in all England.

I hadn’t seen it again until last week except once in the early 1960’s in the painting of it from the Bishop’s Grounds by John Constable. I was in my late 20’s/early 30’s by then and had been sent by my company to visit an elder-sister company in Ohio in connection with technical liaison between the two. I had a week-end to spare when passing through New York and used some of the time to visit the Metropolitan Museum where Constable’s painting of Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds is on display.

I tried to take a photo of the cathedral from Old Sarum but it was too far away for my iPhone’s optical lens to handle in any detail. I had to go back another day, when it wasn’t overcast and raining, lugging along my Nikon DS with its varifocal lens. Here’s a relatively short-length shot taken from the top of the outer earthworks at Old Sarum. I include it because it shows in the lower right corner the campsite on which I was staying as well as the city’s densely wooded appearance when viewed from above. At ground-level it is notable for a congested city centre and ring road with always-present and slow-moving queues of traffic.

Here’s another shot, taken with the same camera from the same position, at a little less than its maximum telephoto setting. Unfortunately this shows the modern high-density housing behind the Cathedral and other buildings around it that Constable didn’t have to cope with – or could exclude from his painting. I think it might be possible to do something similar with Photoshop but I’m not sufficiently familiar with it yet to have made the attempt.

PAINTINGS BY JOHN CONSTABLE

John Constable, the famous English artist who, together with JMW Turner transformed English landscape painting in the early 19th Century, was a frequent visitor to Wiltshire. He painted all the monuments mentioned above, with Stonehenge before its large stones were set upright again, of Old Sarum before English Heritage had changed it into a fund-raising retail outlet, and of Salisbury Cathedral whilst it was still the epicentre of a beautiful medieval city.

The monuments themselves, and the admiration they still evoke, are interesting if you can mentally block-out the claptrap of modern over-population, commercialisation and advertising.

This article on John Constable from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s website shows reproductions of his paintings of them all, including the original one of the cathedral I saw in New York 60 years ago.

POSTSCRIPT TO PART 2

I was very pleased to see from the comments that both sections of part 2 were well-received.

Several people were familiar with the Kennet and Avon canal and the area around it. No new evidence emerged to support or debunk the theories about how Caen Hill got its name though Foxoles added to the mystery by introducing a new one. I had to look up Brythonic to understand it though.

Encyclopedia Brittanica told me

The Brythonic languages (from Welsh brython,“Briton”) are or were spoken on the island of Great Britain and consist of Welsh, Cornish, and Breton.

Foxoles told us

………another possibility might be that it could be from the same derivation as the first element, Ken (of Kennet). This is supposedly from an early Brythonic word cu, meaning dog. So Caen Hill would be Dog Hill. As an aside, Caen Wood in Hampstead is often spelt Kenwood.

I’m thinking of running a Sweepstake with the prize being awarded to the author of a peer-reviewed article referencing sources and establishing beyond doubt whether the name Caen Hill is derived from the language spoken by, in order of arrival in Britain, the

Celts, Saxons, Vikings or Normans.

Tickets will be modestly priced and the prize will be ticket income received (less the organiser’s nominal 50% commission. In the event the adjudicator judges no satisfactory answer has been received the organiser will retain all income received. I shall be the organiser and adjudicator).

Can’t say fairer than that, can I guv. If the sweepstake is popular and receipts satisfactory I shall consider putting in a bid to run the National Lottery.

Spa on the Hill (interesting name – do you live in Buxton?) reminded us the town of Calne is not far away implying that too might be derived from the same source. He remembered it mainly for its sausages and bedsheets (he used the latter to abseil off balconies during boozy schoolboy parties). Sounds to me as though he might have been a pupil at King’s School Bruton. Though I know many Puffins are fairly elderly I think he must have been there long after it was first founded in 1519. He didn’t learn much maths or physics though because he thought ocean currents were formed in much the same way as water swirls around plugholes.

Research has established the way they do that is determined by the size and shape of the localised container and pipes – the Coriolis force is far too weak to have sufficient influence to overcome those effects. Blown Periphery made a similar point when emphasising the importance of information about wind strength and direction, humidity etc, provided to a sniper by the spotter.

The account of my visit to Devon triggered some interesting comments too – The Mighty Schlumpf remembered getting near the top of Dunkery Beacon and becoming engulfed by a sudden mist in which he soon became lost. After stumbling around for several hours (over rough ground and in deep heather no doubt) he finally found himself in a pub at Exford (about 3 miles away as the seagull flies and 1,000 feet lower). I don’t think he remembers much more. By his own account he drank multiple pints when in the bar. Perhaps Mine Host put him to bed to let him sleep off the effects of his exhausting tramp across the hills.

Loyal reader DJM liked the photo of Lynton Parish Church and I thank him for his remarks – I like it too and think its one of the best I’ve ever taken (on an iPhone 7 too, because my sooper-dooper Nikon is too heavy to carry around very often and I didn’t have it with me at the time).

Polar Opposite liked the one of the North Devon Coast and Bristol channel too. That was also taken using the ‘phone’s camera when standing in the churchyard at the top of a precipitously steep hillside above Lynton about 150 feet below.

That takes me on to comments about the Coriolis Force section of my article because Polar Opposite also commented that ” The Coriolis effect is one of those things you think you understand until you don’t.” I think that’s true and probably because it seems to have weird and unsystematic consequences.

In fact it is highly systematic but hard to visualise and think about in the abstract. I’m not sure how Coriolis himself thought about it because he was working on the problem without having available the algebraic techniques of Vector analysis and and its closely related but even harder to understand Tensors used to explain and apply dynamic effects today.

Those methods, weren’t developed until the closing years of the nineteenth century and early ones of the twentieth with the latter evolving from a new branch of mathematics called differential geometry.

Coriolis must have been a genius in the sense of a person with an astonishing mind who had insights others find hard to follow even when they know the result of his thinking.

I can just about understand the Coriolis effect if I remember its direction is always perpendicular to both the earth’s axis and the direction of the object’s movement – or use my specialist knowledge of Vectors with their Scalar and Cross-Products.. I don’t think I could if I hadn’t learned the rule and mathematical technique when young. I hasten to add that I never did really master the more complicated Tensor analysis.

In practice, the Coriolis effect is only significant over long distances or when the object is moving very quickly indeed in certain directions, and especially if all three factors are present. A yachtsman sailing from Penzance to Gran Canaria would find it hard to distinguish the Coriolis effect from all the other vagaries that might affect his voyage. An artillery officer firing a rocket-propelled howitzer at a target twenty miles away, or an astronaut headed for the moon, might miss their targets altogether if they didn’t allow for it.

I’m not too bothered by my ignorance of Tensor Analysis because even Einstein is quoted by one of his biographers as having said or written to the Italian Mathematician and his pupil who developed the theory and published a paper on it in 1900 –

“I admire the elegance of your method of computation; it must be nice to ride through these fields upon the horse of true mathematics while the like of us have to make our way laboriously on foot.”

I console myself with the thought – I bet neither Einstein or the Italians learned how to sail a small yacht at 60 years old – or get to the top of Dunkery Beacon on foot when nearly 86!

We all have our own unique set of skills and capabilities and only feel appropriately humbled when we meet some-one who is better than ourselves at absolutely everything we do. If you adopt a creative approach by developing a few really weird interests the probability of meeting someone like that can be minimised. I might try to develop the sweepstake idea before my carbon is recycled for that reason alone!

To be continued …….

© Ancient Mariner 2022