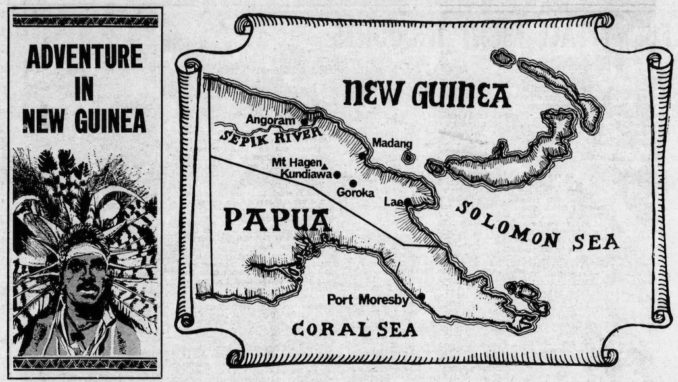

In 1969, my uncle, John Alldridge visited New Guinea to “observe the attempt to weld a primitive people to a modern society”. This is the second of his reports for the Vancouver Sun. – Jerry F

Adventure in New Guinea,

Vancouver Sun – © 2022 Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

It was the aeroplane that opened up New Guinea. And in a country where there are no railways and precious few roads the aeroplane is still the only way to get around if you’re in a hurry.

Probably nowhere else in the world is flying so chummy and so informal as it is up here.

Making a flight is more like catching a bus. Nothing flies strictly according to schedule. Planes take off when they’re full. So you carry your bag out to the aircraft and sometimes squat down in the shade under the wing until the pilot arrives.

No flight lasts very long. Even so, half an hour’s flying in this country, where the mountains rarely fall below 10,000 ft. and huge thunderclouds are liable to close in on you at any minute, can be pretty exciting.

So early in the morning, while the mist was still almost at ground-level, we took off in a squat little Italian Piaggio P166 — known up here as the Flying Pig — and flew east towards Goroka; following the valleys, hugging the mountain ridges where the villages cling like limpets, until we picked up the broad silver ribbon of the Wahgi River.

As we began our descent towards Kundiawa the crumpled valley below suddenly began to break up into steep checkerboard fields, each as regular in shape as a chocolate bar.

In these tip-tilted fields men and women were working, at an angle that would have turned a self-respecting mountain goat dizzy, and made a Lancashire hill farmer sell up in despair.

I realized, with a queer thrill of excitement, that I was looking down on the fabled garden-people of the Chimbu, whose secret valley was first discovered by Michael Leahy only 30 years ago.

Later, as I rode — or rather, bumped and bounced—around these hill-top villages with the District Commissioner in his Land Rover, I learned a great deal about the garden-people.

They must be the best gardeners in the world — not excepting the Japanese. On this impoverished soil, sometimes no more than a few inches deep, they seem to be able to grow anything.

Up here they grow coffee — the finest Arabica — higher than anywhere else on earth.

When an Australian company tried to start a passion-fruit industry and failed dismally they turned over their stock of seed to the Chimbus before they left. The Chimbus promptly planted the passion-fruit among their coffee trees. Now you can open a tin of passion-fruit juice for breakfast, grown up here at 6,000 ft.

When the American Air Force was here during the war these farmers supplied them with carrots, beans, and crisp lettuce, vegetables that had never grown here before.

Looking at those almost perpendicular plots, watching those women doubled up at their back-breaking work, it seems impossible that anything could grow here.

Better brains than mine have puzzled over this. Agricultural experts have come up here all the way from Canberra and been forced to admit these Stone Age farmers have almost nothing to learn from them.

Yet, ironically, the Chimbu gardeners’ basic crop has never really changed in a thousand years. He still raises hundreds and thousands of pounds of the New Guinea Highlanders’ staple diet — sweet potato.

And like all farmers they know the value of money.

Last year the Kundiawa Council — all of them elected representatives from the most thickly populated district of New Guinea — levied from its 90,000 “ratepayers” more than a quarter of a million Australian dollars.

The farmers grumbled, of course, as farmers always will. But they paid up; knowing that most of the money would go to build a new road that will get their coffee to market that much quicker.

Local government on modern democratic lines has come so rapidly to garden-people that even the District Commissioner, who has lived among them for 24 years and is an optimist by nature, is surprised by the speed of it.

Only 10 years ago these villages were still ruled by the stone axe and the bone-tipped spear. Now they have a secret ballot and committee rule.

In last year’s municipal elections one ward was actually contested by a woman. In a country where for generations women have been regarded as among the lower forms of animal life this is progress indeed.

I should like to have stayed a little longer in Kundiawa. It is the nearest thing to Shangri-La I have yet discovered.

A snug little valley locked away among the mountains. Free from distractions. But with an airfield handy in case of emergency. And the most casual “pub” in the world.

At Chimbu Lodge, from the McKirdys — a young Scots manager from Greenock and his Australian wife — you get the same friendly, unobtrusive hospitality whether you are a day tripper or a millionaire on a $1,000 safari. As a matter of interest, among my fellow-guests there were five American millionaires.

Half an hour’s flight over those treacherous mountains is Goroka, the administrative and commercial centre of the Eastern Highlands. And flying into Goroka from Kundiawa is like flying back out of the Stone Age into the twentieth century, with all its complications.

Goroka is very much a show place. A model city — perhaps, one day, a capital city — of the New Guinea of the future. When the Australians have gone and the Parliament of a Thousand Tribes runs its own affairs.

As yet it is a thriving, ever-growing town, strenuously serving the needs of almost half a million people. It has a million-dollar hospital, where no operation costs the patient more than three shillings; a fine new teachers’ training college; an Olympic-size swimming pool; a modern piggery, where imported pedigree Berkshires live and breed in utter luxury; at least three air-conditioned department stores; and the fifth busiest airport in Australasia.

In the trim tree-lined streets of Goroka, where Australian and New Guinean civil servants live side by side, in neat little egg-boxes on stilts (but at different rates of pay), a Chimbu Highlander in his feathers and war-paint would seem as outrageously out of place an as ancient Briton in his woad walking down Leadenhall Street.

Standard dress here is strictly European. And the general deportment is almost painfully prim (except on pay nights, when, under the influence of strong Australian beer, old rivalries and jealousies flare up).

Yet the Stone Age is never very far away.

Reproduced with permission

© 2022 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023