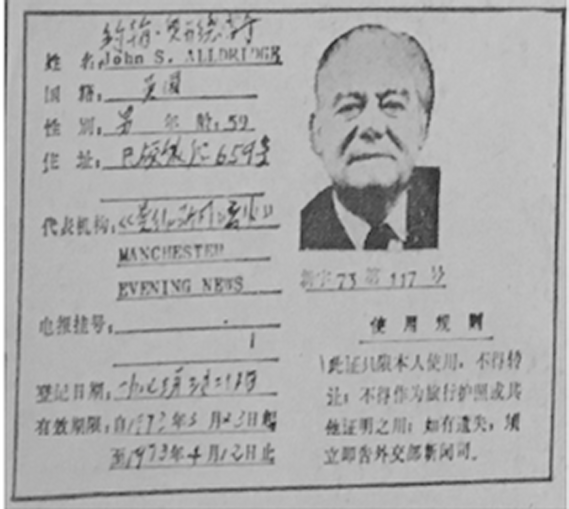

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

Centuries of silk

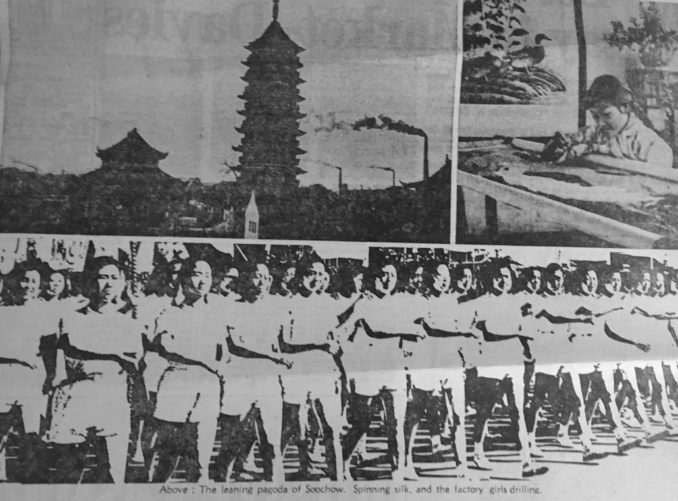

Soochow is an old, old city renowned for its silk, its gardens, and its beautiful girls. If you are really interested in dates, it was founded during the Period of Spring and Autumn. Or, according to our calendar, 514 BC. Which makes it very old indeed. For all its spouting chimneys, it is still a city of narrow, tree-lined streets, of sluggish canals crossed by many bridges. All of which makes it very like a Chinese Bruges. Dominating all is a magnificent old pagoda which for the last 900 years has, like that other tower at Pisa, been leaning at an alarming angle. But it’s still good for at least another 100 years, they say.

Years ago, before Chairman Mao and the People’s Revolution cleaned things up and turned it into just another strait-laced city, Soochow was a pretty gay sort of place. It abounded in fortune tellers, gambling dens, and houses of ill repute, my guide explained to me scornfully. A sort of Ming dynasty Las Vegas, in fact.

Even today, when the iron hand has swept those useless frivolities out of sight, it still remains pretty carefree. Its girls are still incredibly beautiful, able to make even a sloppy boiler suit seem sexy. They have a way of looking at you, those girls, as if to remind you that for all the great sexless proletarian revolution, its not so many generations since the Emperor himself used to send to Soochow for his concubines. And that more than one Soochow peasant’s daughter rose to be Empress of China.

So skilful were the silk workers of Soochow that the Emperor himself came here for his coronation robes; and there is one very old man still living in the city who, as a youngster, worked on the magnificent yellow state robes of the last Manchu Emperor.

There is a school of embroidery in Soochow – in the heavy handed State jargon it is listed as a Research Institute of Embroidery – where maybe 50 supreme craftswomen spend their working lives embroidering from Soochow silk roses and carnations so glowing with life that you can almost smell them. I met a woman of 50 who for 30 years has embroidered nothing but kittens; fat, fluffy, playful little creatures that seem to come gambolling out of the frame at you. And there are teams of women – two and three working together – painstakingly copying in thousands of coloured silks, photographs of the Yangtse Bridge at Nanking, the Shanghai waterfront, and, of course, the birthplace of Chairman Mao.

The work done here is priceless. So fine that it is not for sale. It is reserved for exhibitions and as State gifts to visiting VIPs. So it was sad to learn that these superb craftswomen – who must be among the finest needlewomen on earth – earn no more than a factory worker or a field hand.

But no matter how sumptuous the needlework, it all depends in the final analysis on a small grub called the silkworm. During its months of incubation this hard-working little insect, in between stuffing itself on mulberry leaves, somehow manages to wrap around its body a cocoon of fine silk which, when unravelled, produces an unbroken thread 1,000 metres long.

They have been spinning silk in Soochow since Harold was fighting it out with William the Norman at Hastings in 1066. So I went along to the No 1 silk-spinning factory where nowadays they follow through the whole process from unwinding the cocoon to rewinding the gross silk. My guide was Comrade Mrs Chow, who is chairman of the Revolutionary Committee and therefore director of the factory. Mrs Chow is 49 and started work here as an 11-year-old apprentice. In Britain, that might be remarkable. In the People’s Republic of China, I have learned by now, it’s a commonplace.

I arrived at an awkward moment. The works’ militia was drilling on the factory square; and determined young women in white overalls were lunging and stabbing away with bayonets. I don’t know how they rate as silk-spinners. But I can tell you that with a bayonet the lovely young creatures are downright deadly. The mill employs 1,000 workers, 87 per cent of them women. They work an eight-hour shift, six days a week, unwinding the silk from the boiled silkworms, for an average wage of 40 yuan (£8) a month. Between them they produced something like 250 tons of raw silk last year.

Some of these girls need not leave the factory at all. They have their meals in the factory canteen – the most extravagant lunch costs 20 cents, or about 4p, I noticed. Their children are taken care of in the factory nursery. A factory clinic looks after their health and many of them, whose homes are outside Soochow, prefer to live in, rent free. I was surprised to find how many married women prefer it this way. They told me it got them away from their husbands; a rare luxury for a Chinese woman.

It all seems logical enough. But living this way, the factory becomes your mother, your father, your very existence.

That is not a window!

I went to school in Soochow. Number Nine Middle School, Soochow, is an old school with a history going back 70 years; it is also a very large school. Its 1,000 pupils, ranging from 12 to 17, and its 106 teachers attend some 21 classes of which English predominates. I listened to a class of 14-year-olds reciting parrot fashion “This is a door. That is not a window” in strident English, while a young student picked out the article on a blackboard. Parrot fashion may be, but how many English children of 14 could recite “This is a door. That is not a window” in Mandarin Chinese?

Like every middle-school in China, Number Nine school Soochow is just recovering from the convulsions of the Cultural Revolution during which it was closed for two years. Now, instead of passing on automatically to university or training college, every student here will do a spell in the school workshop. I watched a sturdy lass of 17 turning brass bath taps off a lathe like a professional.

For the future most of these highly intelligent, dedicated, almost depressingly well-behaved youngsters seems pre-ordained – the factory, the farm, or a job in one of the frontier regions thousands of miles from home. It may all be good for the national economy; but it seemed to me an awful waste of talent.

Soochow is a place of magnificent gardens with tantalising names like Joyous Garden, and Garden of the Surging Wave Pavilion, and Lin-yuan Garden, which means Garden to Linger In. I only had time to see one, so on my last morning in Soochow they took me to Cho-cheng-yuan, the Garden of the Humble Administrator. This is the finest garden of them all; a walled Paradise of pools and bridges and moon-windows and tiny pavilions where you can sit and watch the full moon reflected in the water.

The Humble Administrator – who was very far from humble, but a crafty politician who, having wangled himself a post as Official Censor and made a fortune out of bribes until he was found out and banished to Soochow with his loot – had the garden laid out to his own specifications 400 years ago by We Chen-ming, who was one of the four great landscape artists of the Ming Dynasty. He took water as his theme. And so everywhere you wander in this peerless garden you are crossing artificial streams or lingering by lily ponds or walking by artificial lakes only a few inches deep.

I imagine the Humble Administrator, wicked old crook that he was, died a happy man. But his son, a spendthrift and compulsive gambler, made short work of losing his fortune. In one night he gambled away one half of that wonderful garden. But, ne’er-do-well that he was, the man was no fool. He immediately threw up an artificial hill on the other side of the garden wall and had a tiny pavilion built on top. And there, on summer evenings, he could look down on his lost inheritance.

In that garden they showed me an arbour of dwarf trees, the oldest of them 200 years old, but no more than three feet high. It has grown from a pomegranate seed planted by the Emperor Chich Ling when George III was King of England. Each year it still produces one perfect pomegranate.

The Humble Administrator’s garden is timeless. On the walls of one tiny summerhouse some long-dead poet had written “the noise of the cicada makes the garden more peaceful.”

I sat for a moment on the stone seat and listened. Sure enough from the old lilac tree above came the distinct cheep-cheep of a cricket. After the incessant clatter of those looms, the ferocious bayonet play, the strident chorus of 40 children reciting “That is a chair. This is not a window” – it was very, very peaceful.

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player