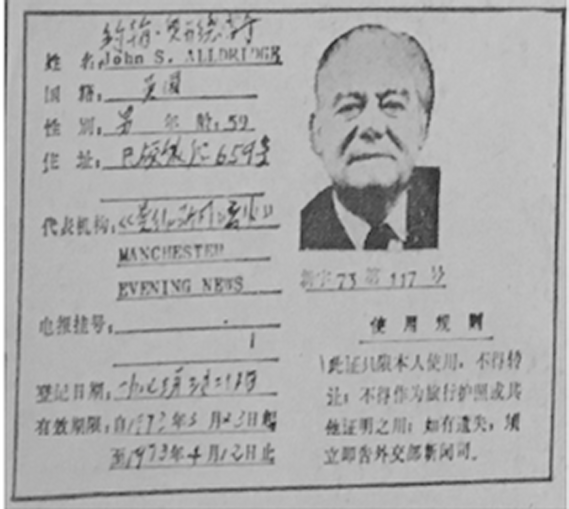

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

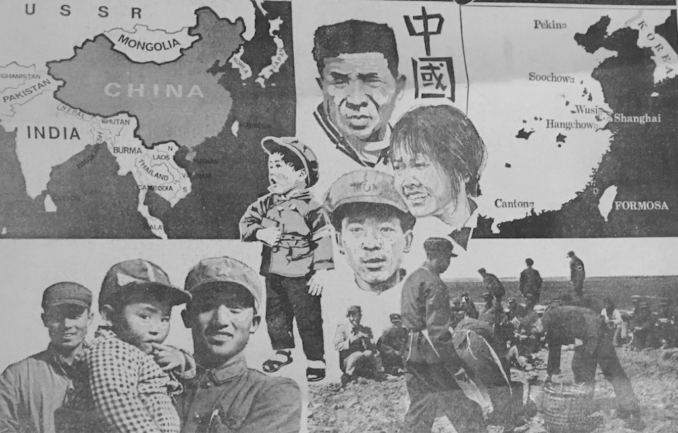

With a population of 700m, China is the largest nation on earth – but here in the West little is known about the life and work of those 700m. Now Manchester Evening News staff reporter John Alldridge has taken up a rare invitation to visit that secret world, and today he begins a fascinating series of reports from behind the Bamboo Curtain. In his first report he looks at the life and work of the People’s Liberation Army.

An army in the fields

Ten miles south of Pekin, driving hard and fast down a road as broad and as straight as the M6, we came to a yellow checkpoint. My driver swerved violently out of the middle of the road, narrowly missing a couple of bullock carts in the process, and obediently pulled up beside it. From where I sat in the back seat I could clearly read the forbidding sign in Chinese, Russian and English: “Out of bounds to visitors.”

But the sentry in his khaki boiler suit with the big plastic star on his cap hardly looked at the little red Press card they had given me. Instead he signalled to a Chinese Army jeep that had obviously been waiting for us, and waved us on our way.

From now on we were under military escort in a land forbidden to foreigners. A land of bare brown powdery earth and spidery trees. A land somehow recalled to life every year by a multitude of peasants, mostly women, working on it with primitive hoes and ox-drawn wooden ploughs straight out of the Old Testament.

For nearly two hours we drove on and on down that road, almost always in a perpetual dust haze out of which convoys of farm carts came lurching suddenly, their swaying loads drawn by mixed teams of plodding oxen and frisky, shaggy ponies; their drivers, thin shoulders protected by thick sheepskin coats, lolling back among the sacks of seed, smoking long metal pipes.

We crossed a river and passed through a town where the whole population – men, women, and children – seemed to be out repairing the river banks after the spring floods. They were filling in the gaps with chunks of stone which a battalion of masons was trimming roughly and rapidly into shape. It seemed from that distance as if an army of ants had taken over those river banks; an army working feverishly under dozens of huge, flapping, red flags driven firmly into the river mud. And as they worked they sang.

We left the town and in a mile or two turned off the road across a bare, featureless plain and presently saw straight ahead of us a group of raw, red-brick blocks rising out of an asphalt parade ground that could only mean a barracks in any man’s army.

In fact, it might have been an Army camp anywhere in England. Except that the soldier doing traffic-control waved to us instead of saluting and a squad of recruits at rifle drill dropped their rifles to clap us as we passed. Somehow I can’t imagine that happening at Tidworth or Caterham. This was the headquarters of the 196 Infantry Division of the People’s Liberation Army.

And there, as if to prove it, was the division’s Commissar, Comrade Din, to welcome us. Comrade Din is a tall, chunky man with a face like rough-hewed granite and eyes that never smile. Gravely he invited us into the regimental common room; gravely he seated himself at the top table under a large portrait of Chairman Mao and, with his junior executives around him, gravely launched into a long and detailed account of the history of the gallant 196th, its aims and objects in peace, and its glorious and assured future under Mao.

The regiment – he told us – was first formed during the Japanese War of 1937-45 out of several guerrilla units and served very actively in North China and Inner Mongolia. During the War of Liberation of 1946-49, by now a full-strength division, it took part in the three great liberating battles for Pekin, Tientsin, and Sanshun Province.

In 1952 it was one of the first units to be sent to Korea – “to foil the Imperialist plot” he explained proudly – where, he claimed, it wiped out 38,000 enemy troops and captured 16,000 rifles and 370 guns of all kinds. Obviously a tough fighting outfit, the 196th.

So much for its part in war. In peace the Army is even more heavily involved. “Chairman Mao teaches us we must always be with the people. The Army and the People are one” Comrade Din assured us solemnly. “We of the 196th have fulfilled the task assigned by Chairman Mao. We are a fighting force, a working force, and a production force”.

Which means that when the soldiers are not on parade they are working in the fields with the farmers or alongside the workers in the factories. At that moment, about half the division was toiling with the townsfolk mending those river banks.

As a regimental unit it is almost entirely self-supporting. It raises its own rice and millet and pork – staple diet of a Chinese infantry soldier. It repairs it own equipment. And even finds time to staff and run a small pharmaceutical factory, turning out seemingly endless quantities of energy tablets and vitamin pills.

The red badge of equality

What really surprised me, as an old soldier myself, was to learn that the People’s Liberation Army had no badges of rank. No more sergeants and corporals, no more lieutenants, colonels, and captains. Only soldiers, squad commanders, platoon commanders, and company commanders. And they all dress exactly alike.

“In the People’s Liberation Army, officers and soldiers are equal” explained Comrade Din. “We have done away with all the old bad habits of officers scolding soldiers and beating soldiers. Whenever our soldiers see shortcomings in their officers, they put forward suggestions for improving them”.

But if there are no badges of rank, how do the men recognise the officers and the officers the men? I asked. “Easy. The commander lives with the soldiers. They know each other”. And if the commander is killed? “The soldiers will elect another whom they know to take his place”.

This same amazing informality also applies, it seems, when it comes to orders. “In wartime we are told by our leaders what must be done. Then officers and soldiers get together and discuss how we shall do it”.

Enough to make and-old time British RSM die of apoplexy.

But not only is this an Army without rank and without direct orders carried out at the double. It is an Army without beer, without women, where gambling is forbidden, where married quarters don’t exist, and where leave comes every six months – if you’re lucky.

You would think that a Spartan life like this would hardly be good for recruiting. Yet they tell me that so many young men apply to join the Army that even if accepted, the lucky ones can’t expect to serve longer than three years at the most. They’ve got to give up their job to the next man waiting in the queue. (In the Air Force they can serve for four years and in the Navy for five.)

But some things don’t change. In the soldiers’ Club of the Second Company – a bare room spotlessly clean dominated by a ping gong table – they showed me the history of the regiment to date, beautifully written by hand, the regimental battle honours won in Korea and a grisly display of war trophies, including a Japanese officer’s sword, an American officer’s Remington revolver, and some unknown GI’s infantry carbine with the name “Susie” still carved on the stock. I wanted to ask had they any British souvenirs. But thought better of it.

We inspected the barrack-rooms, which were like barrack-rooms anywhere. Blankets squared for inspection, mattresses dressed by the left. But no pin-ups in the PLA. Instead, there was a wall newspaper, with drawings and poems and political thoughts contributed by members of the squad.

“Criticisms are freely welcomed” the platoon commander assured me. One criticism I noticed was certainly pungent. “This wall newspaper isn’t lively enough. Why not pep it up?”

I joined them for lunch in what I suppose in any other army would have been the officers’ mess. They filled my plate with great dollops of smoking beef, dumplings stuffed with meat, bean curd, and home-grown rice. All meant to be eaten with chopsticks.

I asked if this was a normal lunch for the People’s Liberation Army. “Chairman Mao has said: ‘We defeated a well-equipped army on millet and rice,’ so the PLA lives largely on millet and rice. But since you are our guest today we have added a few little extras,” said the platoon Commander, his mouth crammed with about half a pound of fillet steak.

Tea was taken – as you might say – up on the range, where we watched some fancy shooting with rifle, semi-automatic rifle, heavy machine-guns, and rocket launcher. There was also a fearsome demonstration of a horrible little monster called a parachute mine, like a bunch of lethal grapes, that blew up everything on sight in the target area.

This was obviously a demonstration platoon going through its paces. So it was difficult to judge. But if the shooting of the 196th is only half as good as this deadly target practice, then they must be a pretty formidable lot.

When the serious stuff was over they beckoned us to the firing line and, with half a dozen other correspondents, I had a go at 10-rounds-rapid with a Chinese-made light automatic rifle. A very light-weight weapon with a rather sticky trigger action but almost no recoil. It is nearly 30 years since I handled a service rifle. And only one of my shots fell on the target but from the applause you would have thought I had won the King’s Prize at Bisley.

Before we left we had to attend a camp concert specially got up in our honour. It was the strangest camp concert I have ever attended. A highly talented company of young soldiers – men and girls – danced, sang, told funny stories, did conjuring tricks even managed an extract of patriotic opera.

But from that packed service audience, not a wolf whistle. They just clapped politely and in strict tempo, like 500 well-drilled automatons.

On the way out of camp we passed a fatigue party jog-trotting back from the town. They wore full marching order, and in addition to their rifle, each man carried a sickle or a billhook or a builder’s hod. As they passed us, they were singing. A stirring, blood-tingling marching song I have heard blasting from the radio morning, noon and night. In English, the title means “The East is Red”.

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player