© bobo, Going Postal 2021

On the morning of 19th June 1312, as reckoned by the old style Calendar, a party of mounted men left Warwick Castle. My Lords Leicester and Warwick rode in front on nobly caparisoned destriers, with a retinue of half a dozen armed men on serviceable rounceys following behind. In the midst of these, riding a broken down old palfrey fit only for the knacker’s yard, was a young man once one of the richest and most powerful in the kingdom. Used to wearing the finest of raiment, the rags of whatever he was dressed in when he was arrested five months ago would have been wretched enough but he had spent the last few weeks immured in the oubliette at Warwick and as this formed the sump of the castle’s primitive sewage system, even these tattered threads were saturated in filth and ordure.

The party was to deliver their prisoner to further confinement at Kenilworth Castle but halfway along their route, at Blacklow Hill where an outcrop of honey-coloured rock stands out on the crest, they halted.

The Lords waited as the men-at-arms hustled their prisoner off from his horse and up the slope. There was an arc of silver against the sky and a gout of crimson across the greensward and Piers Gaveston, once arguably the most powerful man in the kingdom, lay dead, beheaded. This was vengeance at the hands of a coterie of rich and influential men, whose antipathy Gaveston had expended a lot of time and energy over the last few years in soliciting.

Without any sign of undue perturbation the party remounted and continued on their leisurely journey, leaving Gaveston where he lay. We have it on impeccable authority that shortly afterwards four shoemakers arrived at the scene and sewed the severed neck of the corpse back together. They then gently and reverently bore the body away to be buried. They chose not the church at Leek Wootton, only a mile hence, nor the priory at Stoneleigh barely five miles distant. But instead they carried their burden some twenty-five miles, the head lolling grotesquely all the way, to the Dominicans at Oxford where it lay embalmed but not interred for the next ten years. This may all seem incongruous, but we are in the High Middle Ages now and we must learn to expect the unexpected.

© bobo, Going Postal 2021

If you know anything at all about Edward II, you will believe that he was a homosexual and in this you are probably correct. If you know anything else about Edward you may believe that he met a spectacularly unpleasant end and in this, as I hope to prove, you are almost certainly in error.

By the Treaty of Montreuil in 1299, Edward I contracted to marry Margaret, the seventeen years old sister of King Philip IV of France. The blushing bride had her Special Day that same winter, standing before the altar in Canterbury Cathedral next to her white-haired husband King Edward; some forty years her senior, scarred and battered, and irascible to boot. By the same treaty, Prince Edward was betrothed to Isabella, King Philip’s daughter. However Edward would have to wait a little while for his nuptial feast, as Isabella was at this time only eight years old. And first Edward would meet Piers.

Gaveston’s father was a Gascon knight who had done Edward I much good service in the king’s Scottish wars, and who was given a place at court as a reward. As Piers grew up he earned a reputation for his skill at arms and was reckoned the second best tourney knight in Europe, which is far from faint praise. He was good looking and had charisma, and impressed the old king so much that he was selected as a companion for the young Prince Edward.

When the two met the attraction was mutual and powerful, and almost immediately occasioned unfavorable comment. It is not my intention here to examine the arguments pro and con the possible homosexual element of Edward’s relationship with Piers. Rather we will look at the facet that proved to be the most destructive: the favouritism.

Edward showered Piers with gifts; money, jewels, silks and so on. But it was the largesse of land and titles that aroused the most resentment. Whilst the old king lived this was kept pretty much in check, but when Edward himself came to the throne the brake was off.

You could ostentatiously swan about the court in purple silk, a colour usually reserved for the king, and incur only sour comments. You could make up rude names for the nobles, and they would do nothing bar smile thinly and store each slight up for a future reckoning. But accrue land, title, precedence and rank above them and they would nurse murder in their hearts and come together to hatch plots. And Piers committed all these faux pas in abundance.

The nobles’ anger simmered and eventually broke forth in a more-or-less open revolt, and the fortunes of the two sides seesawed back and forth. But eventually Edward was reduced to a single castle, Scarborough, where he and Piers surrendered with his young wife Isabella. The nobles enforced a settlement whereby Edward kept his crown but submitted to the guidance of a council of their number who ensured that he put their interests above those of anybody else, which was precisely how things should be in a well-ordered kingdom. The nobles also stipulated that Gaveston be ‘given over to their custody’ which ended as we have seen above.

Jean Froissart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Now throughout all these vicissitudes of their life together thus far, the young Queen Isabella seems to have accepted things with equanimity. She trudged loyally behind her husband as he waged sporadic warfare against the recalcitrant barons up and down the country and on occasion she put her own life on the line, such as when she sought entry to the castle of an unfriendly noble in order to give the King an excuse to demand entry and seize the castle for himself. Tellingly she also did not complain (much) about sharing the King’s affections with Gaveston. She was three months pregnant with the first of the four children she was to bear Edward when Gaveston met his fate, and she can reasonably have expected matters to improve thereafter. Which they did. For a while.

Edward’s grave failing as a monarch was that he squandered the goodwill of the English magnates during his infatuation with Gaveston, and was never able to recoup it thereafter. This allowed the evil of factionalism to infect the body politic and those great landowners who should have all been in the King’s Party began working for their own narrow interests, and over the next few years the King slid inexorably towards the status of pawn.

Edward made matters worse by adopting a new ‘favourite’, Hugh Despenser the younger. None of the baronial cliques saw eye to eye with each other but the parvenu, rapacious Despensers were universally loathed, and achieved the almost miraculous feat of causing the other nobles to coalesce against them. And, of course, against the king.

It did not help that Hugh the younger was not content to lol around the court, bedecking himself in jewels and silks. Hugh was an astute and aggressive politician and, in essence, maneuvered himself such that he was able to shut out all the other great families from any access to the King. By 1320 it was clear that another civil war was brewing.

Isabella despised Hugh, and the feeling was reciprocated. Hugh slighted her in public and persuaded Edward to give him jewels and grant him lands that Isabella held. Hugh set himself to be a wedge between the King and Queen, and it was rumoured that he was petitioning the Pope to annul the Royal marriage. But the final straw came when Hugh began trying to get her first born son, also named Edward, taken out of her care and firmly in his own clutches.

From this point on, Isabella played her cards remarkably shrewdly. She was so successful in her dissimulation of loyalty that when, in 1323, King Edward decided that his young son be sent on a diplomatic mission to the King of France, the Queen was chosen to accompany him. This was the moment she had been waiting for.

With her and the young Prince Edward safely on French soil, Isabella declared herself a widow, donned a widow’s garb and raised the flag of rebellion against the King. She also began living in open adultery with an exiled English noble named Mortimer, who had escaped captivity at the hands of the King by the Errol Flynn-esque expedient of getting his jailers drunk and abseiling from his cell window on a rope of knotted bedsheets. The French Court was scandalised by this liaison, but also charmed by the notion of creating trouble for the English king. There were plenty of disaffected and disinherited English nobles in France and the Low Countries, and with a little French help and money Isabella and Mortimer were poised to launch an invasion by the autumn of 1326.

AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Their fleet left from Dordrecht in the Netherlands on 23 September, and sailed into the River Orwell in Suffolk the next day. They were greeted by the Earl of Norfolk and stayed overnight in his castle at Walton-on-the-Naze. The next day they set off for Bury St Edmunds, Isabella fetchingly dressed in black .

There was no serious resistance. Northampton, London and Bristol fell in short order, and on 19 November Edward, Hugh and a few stragglers were betrayed at Neath Abbey and captured.

Edward was imprisoned, but Isabella had something special in mind for Hugh. He was taken to Hereford and given the courtesy of a sham trial. He was found guilty, to no one’s great surprise, and was taken out to the market place for execution. The Chronicles of Froissart recalls the details unsparingly.

Despenser was first hanged, but was cut down before he lost consciousness. His virile member and his testicles were then cut off and burned before his eyes, and his stomach was slit open and his bowels dealt with likewise. An incision was then made in his chest to remove his heart, at which ‘he gave forth a moan such as was never before heard in the kingdom’ and he finally expired.

Isabella had had a viewing gantry erected directly in front of the scaffold in which she sat, demurely sipping wine and nibbling on sweetmeats, throughout the entire revolting spectacle. She never once took her eyes from those of her rival as he was slowly and excruciatingly butchered.

Isabella was a formidable lady, no doubt, but one around whom it was perhaps not possible to feel too comfortable.

The realm of England lay at Isabella and Mortimer’s feet, but they had a problem. Ideally they would reign as joint regents until the young Prince Edward, barely ten years old, gained his majority, but King Edward was still alive and stubbornly refused to die.

He was first held at Kenilworth Castle, under the relatively benign regime of Henry of Lancaster. Here the King signed the formal. but legally highly dubious, Act of his abdication on 16 Jan 1327. Prince Edward was crowned King Edward III at Westminster on 1 February, and on 3 April Edward II was removed from custody at Kenilworth by Thomas de Berkeley and Sir John Maltravers, and taken to Berkeley castle in the West Country. There are no confirmed sightings of him alive after this date.

On 21 September, the Royal Court officially announced that Edward II was dead. A Coroner’s inquest, comprised of handily compliant local gentry, was held at Berkeley and in short order ascertained that, yes, the body before them was that of Edward II and that, yes, he was dead; although no apparent cause could be ascertained. Certainly nothing that would redound to the discredit of Isabella and Mortimer. Oh dearie me, no. Perish the thought.

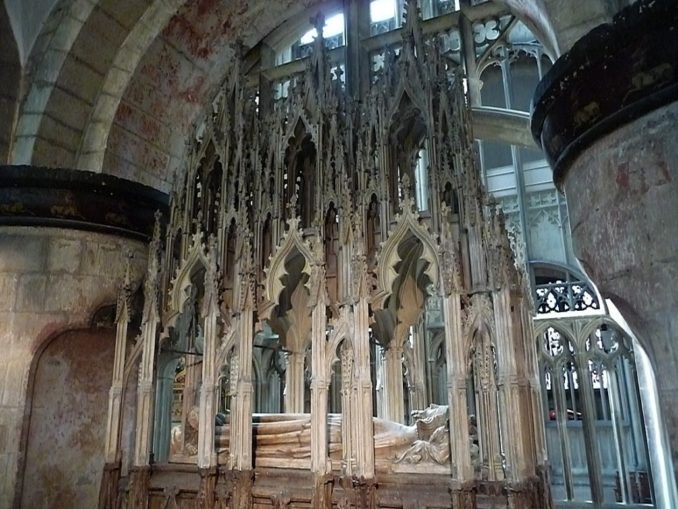

Edward’s body was embalmed and his heart was placed in a silver casket and sent by Henry de Berkeley to Isabella, who received it with a hypocritical effusion of grief. Hypocrisy was also the keynote of the lavish funeral at Gloucester Cathedral in December. The hearse was drawn through the streets by four horses caparisoned with the royal arms, and the catafalque was leafed with gold. The magnificent sarcophagus is still one of the masterpieces of Anglo-Norman funerary carving, and Isabella again wore the widow’s raiment which on her was so becoming.

Chris Gunns / Edward ll tomb

Almost immediately rumours began circulating about the circumstances of Edward’s death. It was said that he was held in close confinement until a close but abortive rescue attempt by a local posse of loyalists made an expeditious demise desirable. At first de Berkeley cast him into the oubliette, where it was hoped the King would expire from gaol fever. The King’s constitution proved too strong, so a hired assassin was bought in to finish the job.

In the earliest redactions of the story Edward is pressed to death with a heavy oak table, or smothered with a bolster. By the time the tale has reached its full grand guignol expansiveness in Marlowe the killer has a suitably Mephistophelean name, Lightbourne, and Edward dies by having a red hot poker thrust up his fundament in a clear reference to his having committed the Sin of Sodomy. And it is this latter version which has seared itself, so to speak, into the English consciousness.

But there is, possibly, a more happy ending. It takes the form of an undated letter to the court of Edward III. It is from an Italian priest, Manuel Fieschi, who holds in absentia an English benefice but who is currently at the Curia in Rome. He begs to tell his majesty that he heard in confession from Edward II himself the true story of his escape from Berkeley Castle.

Fieschi knows in considerable detail the events of the King’s captivity. He knows that the king had to be moved at short notice to avoid a rescue attempt and he knows where to and when, and he knows the names of many of the people involved and in every case he conforms with the facts as we believe them to be.

But then he goes further. Edward was still in Berkeley Castle when he was made aware that the assassins were on their way to dispatch him. A servant offers to change clothes with him, and thus attired the King leaves his cell. He reaches the castle gate undetected and finds the porter asleep so he slays him, takes the gate keys and leaves the castle. The assassins find the King has gone and, fearing Isabella’s wrath, present the porter’s body as his at the inquest. Meanwhile Edward has made his way to Italy where he lives out the rest of his days in anonymity as a hermit, in quiet contemplation and prayer. On his deathbed he summoned a priest, Fieschi, and made known his true identity.

It is possible. Certainly Isabella and Mortimer would have not wanted the news of the King’s escape to get abroad, hence the hurried inquest in front of Berkeley castle nonentities rather than the court at Westminster as was normal protocol in the death of a monarch. It is wholly possible.

Berkeley Castle still stands entire, and is worth a visit if you’re ever down that way. And should you stand in front of Edward’s tomb in Gloucester Cathedral, consider that the body lies within may not that of a monarch but rather that of a nameless substitute. And furthermore consider that the heart thereof was once entombed with a Queen, for by her dying wish Isabella was interred in her wedding dress and with the silver casket containing the purported heart of her husband.

Once Isabella got her teeth into a role, she was loath to let it go.

REQUIESCAT IN PACE EDWARDUS SECUNDUS REX ANGLORUM

© bobo 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file