© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2021

April 1984 suffered its share of chill winds, further proof that the final quarter of the 20th century drew towards an ice age. But the clocks never struck thirteen and the masses making their way through the capital’s evening rush hour were more likely to be bound for the litter-strewn doorway of a Nelson Mandela House (in a nuclear-free zone) than Winston Smith’s decrepit Victory Mansions. Likewise, there was no need for a contrived war, there’d been plenty of real ones; Falklands, Cold, Northern Ireland, mutinous trades unions.

As for a Ministry of Truth, with only four television channels and half a dozen London dailies, a handful of commentators could convince the proletariat that the real 1984 arrived nothing like the propaganda and surveillance nightmare predicted by Orwell. Let them think that.

On this day, if Big Brother spied out from a gable end in fashionable Pimlico he would see a couple braced before the cold wind as they left the high street tube station. She was slim, inches shorter than he and wore unfashionable, flat, sensible shoes. A narrow and pinched face was chic for the times but was spoiled by her hair which lay straight, short, mousy, even boyish. Her coat being a pass-me-down from a girlfriend the shoulders appeared ill-fitting rather than TV soap bitch padded. In a soft voice, she spoke to her companion like a conspirator, often glancing towards him. Her accent sounded of Received Pronunciation with a hint Celtic fringe, a London girl from an unthreatening hinterland. His voice sounded flat, unstridently Northern, polite, Whitehall briefing room fine-tuned.

He wore an off the peg dark suit which fitted as if tailored. Black leather shoes and a pale blue tie accompanied. From a distance, he presented as nondescript as the sunless April evening sky. What did stand out, close to, were his blue eyes. They darted back and forward in hunger. Beyond the business uniform; dark brown hair, average height, in his twenties, unmemorable. A grey man, made even more anonymous by a brown scarf across the bottom half of his face. The spitting rain permitted her an upturned collar. Without her lips being seen, she was able to congratulate him on his promotion.

Fashionable but not yet gentrified. They paused next to the railings of a cheap hotel housing migrant workers in a London of three hundred thousand unemployed. Rooms from £10 a night, shared bathrooms, toast and tea from an industrial teapot for breakfast. The couple lingered, chatted with lowered voices, glanced around with care. Anyone following had an opportunity to make a mistake and reveal themselves.

“Is Big Brother watching us?” He asked.

“Don’t think so,” she assured me.

Subterfuge suspended. The two of them were the two of us, myself and my colleague Natasha. Coast clear, we walked along Moreton Terrace towards Lupus Street, making a beeline for our respective apartments in the Dolphin Square complex.

“Understand you’re now called Ashley Worth,” she said.

“My identity became compromised in Ulster,” I told her. “Should I double barrel it? What do you think? Maybe Worth-Saying? Helps if the name fits the job. Mr Taylor the tailor, that kind of thing.”

“The exciting life you lead. I’m always plain, boring Natasha Williams,” she confided in me. “The ordinary girl from the valleys.” A lot of effort went into the last vowel. It was dragged out, held onto as a chapel preacher might hold on to his favourite name from the Bible.

“Don’t knock being ordinary,” I recommended.

“They say you’ve been promoted to keep you away from a public inquiry. Setting up suspects for a shooting. Tell me it isn’t true?”

“Don’t knock that either.”

“AIDA,” I continued. “Attention, interest, desire, action. The action is always on the bottom right corner of the page.”

A fake accent, Ulster-Scots, helped with the explanation, “Mr Softie, we know what you are. We’ve seen the pokey van parked outside the big mon’s hoose when the big mon’s at work.” Back in my normal voice, “Get them killing each other, saves some poor sod in uniform from having to do it.”

She changed the subject.

“Done anything heterosexual of late?”

“N.O.Y.B,” I replied.

“Seriously, it’ll help your vetting.”

I groaned.

“Yes, I’m back on vetting, as well as other things,” sighed Natasha. “Such a lot of them are working on the strike. And I have to vet you.”

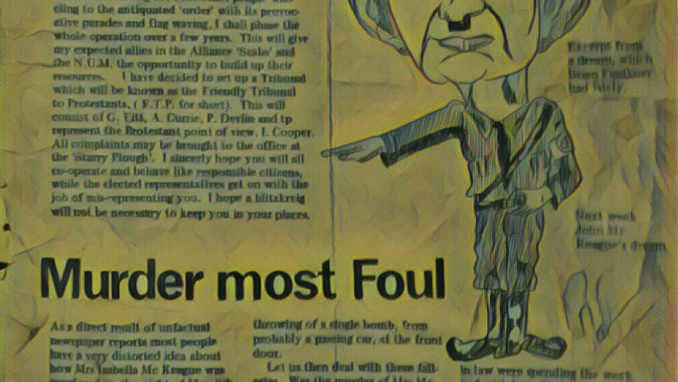

The difficulties in the coalfields reminded me that I had product folded in a pocket. A page from a red top newspaper which was going to be my exhibit number one. Not the front page with its four-inch high headline about the month-long miner’s strike which sapped every Government department’s manpower. No, I had torn out the fag end of one of those bottom right columns. It caught my eye having, I presumed, been placed where it might drop something into the public conversation without dropping something into the public conversation. So to speak. It might even have been targeted at me. That’s how these things were done. It was called ‘narrowcasting’.

“A little girlfriend in Ulster, nothing serious, nothing that was ever going to last.”

“By little girlfriend….,” she rolled her eyes.

I smirked. A sudden sparkle touched the dull day.

“Just about my age, therefore your age, physically. Older than you mentally and emotionally,” I added, returning the tease. “Nothing heavy. Ended as good friends.”

“You mean she wouldn’t let you. A name?”

“Yes, she had a name and didn’t want to leave Ulster. Family, friends, roots. Jealous?”

In the past, what Natasha had told me of herself I had been fool enough to believe. An NCO’s daughter, she’d lived on army camp, after army camp, after army camp, until an austere girl’s boarding school, all bullying and cold showers, became a real home. Or so I believed.

“Your little squeeze would rather be tarred and feathered, have her head shaved and be chained to a lamppost than be with you?”

A different vowel was dragged this time, “shaaved”. More unheeded evidence that all was fake.

“Got to move on,” I observed.

“Speaking of which, it might be worth being social at the next social,” she advised. “Presuming you turn up for it. And make sure you do. And make the effort to mix. Don’t just stand in a corner and expect me to come and rescue you.”

“I’m not a people person. Hold on, I thought I’d been rescuing you?”

“Despite what you may hear, the high-ups are terrified of another scandal,” she said. “Acquittals or no acquittals, everybody’s on pins. From now on, wife, kids and church look good on the vetting. No more free spirits.”

We’d reached a high wall behind the townhouses on St Georges Square. This was a private road but a right of way to Natasha’s Dolphin Square ‘house’. Cold seeped into us. She offered me a cigarette which I declined. For shelter, she placed her head against my shoulder and tried for a light. Between her centre parting, I could see a thin line of bare scalp, uncovered honest flesh. Mousy brown strands of hair emerged from it like an elixir from a spring. I must concede, I found her attractive. Looking up at me she drew on her cigarette giving it a lively orange tip.

“I’ve had one of my bright ideas,” I told her. “Ball’s rolling, I’ll tell you about it upstairs. Are we being followed?”

She shook her head. A moment later we had passed through the side entrance. Inside, a lift waited for us, steel doors open, mirrors and musack beckoning. We used the discreet stairs instead.

“You’d think they’d want more mines, not less, if there’s going to be another ice age,” I barked to the echoing stairwell, seeing my own breath as we struggled up the freezing flights to her rooms.

Natasha Williams’s apartment faced into the complex’s quadrangle. It was on the seventh floor. My apartment was on the third floor at the far end (the town end), near to the shopping arcade. Close to the bistro and swimming pool, I lodged in the posh end. Posher still, my accommodation faced outwards and sat on a corner, therefore pointing in two directions at once. Between us, Natasha and I enjoyed multiple triangulations of observance. God had made each of us for a purpose and then paired us off.

After holding open a landing door for her, I followed her onto her corridor. Built in the thirties, the theme was ocean liner nautical, although the house names were military. This was the seventh floor of ‘Hood’. Long and narrow hallways connected rooms as though cabins on a deck. Firedoors were of teak interrupted by porthole shaped glass and polished brass. Outside her apartment, she hesitated. All seemed well to me but that didn’t stop my companion from whispering,

“Someones’s been at the door.”

There was no sign of any damage, but then there wouldn’t be if forced by a professional. One learns to trust the female’s intuition. Natasha put her fingers into her hand-me-down coat looking for her door key. Threatened by name in Ulster, I had permission for a concealed firearm. I glanced to my left and right, wary of terrifying an insignificant civil servant, smalltime soap star or minor member of the Royal Family. Such were the other tenants. Both directions being clear, I drew my gun. In one silent deft movement, Natasha turned her key in the lock and pushed the door open. I stepped inside, Natasha followed.

To be continued…..

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player