I was able to reach a conclusion on the most suitable hull material and shape for my yacht based mainly on what may be called desk research – reading books and magazines.

To some extent that was also true when choosing the most appropriate equipment above and below decks but another contribution to my understanding and conclusions came from investigations into the designs and factories of particular builders. Those also involved commercial issues but for narrative purposes this article and the next will concentrate on the technical aspects.

Until the Englishman Henry Bessemer invented a new method of making steel in large quantities in the mid 19th century most boats and their masts, sails and ropes were generally made solely from organic materials – wood, hemp, manila, sisal, etc. Cast Iron made a brief appearance in large ships in the first half of the 19th century but it wasn’t until 50 years later that inorganic materials started to be widely used. That trend continued apace as the chemical and metal-making industries developed using the newly discovered Oil and Gas hydrocarbons and other minerals.

But in many parts of the world the old materials and techniques are still frequently encountered so an overview such as this can usefully refer to them all.

The first sails were square, made of papyrus by the Egyptians, and suspended from a spar or yard mounted at right angles to the mast (Square Rigged). Essentially, such craft can only sail downwind.

A few centuries later triangular sails suspended from a spar mounted at an angle to the mast were developed in the Middle East ( Lateen Rigged) and in the Far East squarish ones again supported from a spar but having many horizontal or inclined battens to keep the sail taut at all times and angles (Junk Rigged). Both these types had the advantage craft using them could make some progress in a desired direction against the wind as well as when it blew from astern.

© Ancient Mariner, Going Postal 2020

© Ancient Mariner, Going Postal 2020

“File:Paceship PY 23 sailboat Woodpecker 2285.jpg” by Ahunt is marked with CC0 1.0

Both configurations have been used in leisure yacht designs with Blondie Hasler’s 26 foot long, Junk Rigged Jester, in which he came second in the first Single Handed Transatlantic Race in 1960 being particularly famous. The third home in that race was Cardinal Vertue, a 25 foot long wooden boat designed by Laurent Giles, but she was Bermudan Rigged.

Matthew Haywood, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bermudan rigging is the type most commonly used on modern yachts with the sails applying both forward and sideways forces to the hull enabling them to sail somewhat closer to the wind than the Lateen and Junk types. When sailing upwind a forward force is formed by the shape of the sails causing the air flowing over them to generate higher pressure on the concave side.

This style was determined empirically about 300 years before engineers used the same principle to design aeroplane wings. Originally Bermudan mainsails had a loose foot but it was soon found shape could be improved by attaching the sail to a boom with its own positional controls.

The sideways force and heeling moments from wind pressure on the sails is counteracted by the weight of the yacht’s keel and water pressure exerted upon it and the immersed hull. The force also causes a certain amount of sideways movement of the boat called leeway and designers have to compromise their other objectives to accommodate the amount of leeway they think their designs can be allowed to suffer.

The shape of each sail is controlled by “Halyards” which pull them upwards and “Sheets” which are run from the lower edge or free corner called the “Clew” to a point near the stern of the boat from which they can be tightened or loosened.

The forces in these sheets depend on the size of the sail and can become very large and difficult to handle in strong winds. Most yachts are equipped with “winches” providing magnification of the tensions that can be applied to the halyards and sheets through the use of gears.

Even so, above a certain length of boat, the foresail can become so large it is too difficult to handle safely. A designer or owner may then decide he wishes to have the same total sail area to provide the forward force necessary but to have two smaller foresails instead of just one that’s very large. That can be achieved by installing an additional “Stay” part way down the mast to a point on deck between its foot and the bow and hanging a “Staysail” from it – the yacht is then said to be “Cutter Rigged”.

The need to compromise between different objectives permeates absolutely everything involved in yacht design and ownership. Another example of this truism is in deciding the material and shape of the sails that also influences the way in which the mast is supported.

In the 1990’s most modern yachts were equipped with sails made from Polyethylene terephthalate, (PET) more popularly known at the time by its brand names Terylene (in the UK) and Dacron (in the USA), patented in the UK in 1941 but now used very widely indeed throughout modern life.

New synthetic fibres have been developed over the last 25 years or so. The driving force has been the search for easily worked and manipulated cloth made from lighter and stronger fibres that are not vulnerable to UV radiation, brittleness or chafe and not too expensive.

That’s a tough set of incompatible objectives, so many cruising yachts are still equipped with sails made from Terylene/Dacron that need to be replaced from time-to-time as they stretch, wear and become damaged by radiation (despite being protected as much as reasonably possible with heavier cover materials when folded on the boom or furled around a stay.

The cut of sail chosen also depends on one’s priorities. Those seeking speed will choose a low cut sail that just clears the side deck but can get caught in waves when heeling and obscures the helmsman’s forward view. Cruisers on less strongly crewed yachts may prefer a higher cut sail, like a “Yankee”, that provides less forward force but is much less likely to dip into the water and leaves an unimpeded view beneath it. It won’t surprise readers to learn that was my own choice.

Usually, boats shorter than about 40 feet have just one mast and I decided a Bermudan Rigged Cutter with a single mast was the best choice for the size of yacht I wanted. Furthermore, thinking I might need to sail single-handed at some time I decided roller furling gear for each foresail would be a huge advantage.

Instead of the front of each sail (the “Luff”) being supported by clips from its stay it would be attached to a slot in an aluminium foil around the stay that could be rotated by winding a “furling rope” around a drum at its base. This makes it possible to change sail area at any time by pulling on ropes in the cockpit instead of having to go out on deck in potentially rough weather.

The ropes, pulleys , clips and so on used to attach and control sails is called “Running Rigging”. That for furling foresails operated from the cockpit includes rollers at the top of the mast over which the halyards can be run, deck-mounted blocks from the bottom of the mast to the cockpit and additional winches with which to haul and tighten the ropes. Similar routing equipment is required for the mainsail halyard and for the downhaul on the boom needed to stop the foot of the mainsail from rising so they too can be operated from the cockpit.

Some designs take this idea even further by installing mainsail furling gear, either behind the mast in a vertical position or designed to rotate the boom and thus wrap the sail around it.

I decided those latter ideas would be “A Furl too Far” for me because I thought the complexities might result in jamming of the gear resulting in being unable to reduce sail rapidly when it was essential to do so. That meant I would have to use a traditional “Reefing” process by means of which sail area can be reduced in strong winds. This entails leaving the cockpit and going onto the coach-house roof to pull the sail down until a ring sewn into it can be passed over a hook on the mast with surplus cloth being folded over the boom and secured to it using short straps whose ends are tied together with a “Reef Knot”.

If the wind gets even stronger – above , say 35-40 knots – it becomes necessary to reduce sail even more than is possible with furling foresails and a reefed mainsail. A Storm Jib and Trysail cut from very strong sailcloth and with even less area can then be used to maintain forward motion without excessive heeling.

The regular sails will have been completely furled or lowered and secured before these storm sails need to be raised – but how should that be done when it becomes necessary? A popular answer is to have a spare foresail halyard to pull up the jib that will have a wire sewn inside its luff for strength and stiffness, and a separate track fixed to the mast up which clips attached to the Trysail can slide.

At the opposite extreme it can be difficult to make progress if the winds are very light – less than 10 knots say. Use can then be made of a Spinnaker or Cruising Chute – these are alternative foresails made from lightweight cloth with a cruising chute being permanently attached to the hull near the bow whereas a spinnaker flies with both lower corners detached from the hull though with one probably held away from the mast by a pole attached to it.

Two more ropes, going over additional rollers at the top of the mast meet these needs – one as a “Guy” to raise and secure a pole holding the clew of the sail away from the hull, and the other as a halyard for a Storm Jib.

Some 5 years later I found the Cruising Chute I bought kept splitting if I tried to fly it in winds of more than about 12 knots and in the end I tired of getting it repaired. I gave it away in Miami and thereafter only used the mast-mounted pole occasionally to hold out the regular Yankee. If doing things all over again I’d probably do without the chute though I’d keep the pole and spare guy/halyard.

Masts and Booms on the type and size of yacht I was planning to buy are usually made from aluminium to be light but strong enough to withstand forces applied to them by the sails and rigging and are fully capable of carrying the weight of a heavy crew member. That is necessary so inspection of the wheels over which the foresail halyards run, and maintenance of lights and instruments at the top of the mast, can be accomplished.

In strongly crewed yachts a halyard can be used to haul a crew member up the mast in a “Bosun’s Chair” (a very basic “canvas seat”) but bearing in mind I might need to sail singlehanded I decided mast steps would be needed. I also decided folding ones made from aluminium would produce less windage and would be less likely to suffer from Galvanic corrosion than other types made from a different material.

A mast can be fixed to the hull at its foot either by penetrating the deck and continuing down to the keel or by terminating at deck level in a special ‘Shoe’ supported from below deck by a compression post that is itself attached to the keel. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages but both require the top of the mast to be held as closely as possible to a fixed position by “Stays” to the Bow and Stern of the Hull and by “Shrouds” to each side. This “Fixed Rigging” has to be “Tuned” by pre-stressing the Stays and Shrouds using “Bottle Screws” to exert a downwards compressive force from the top of the mast to the Keel.

© Ancient Mariner, Going Postal 2020

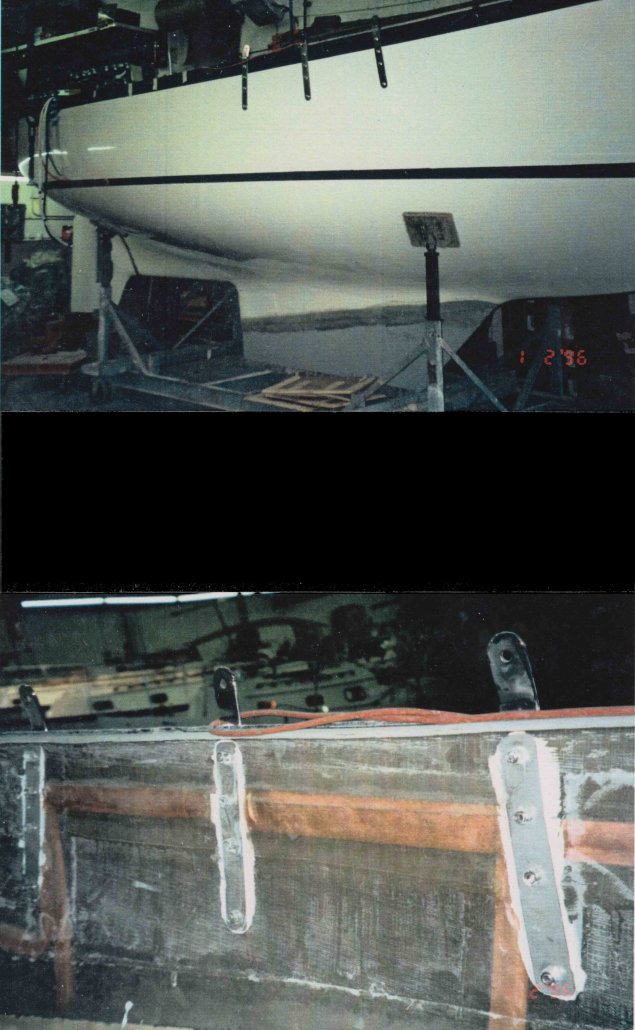

In this photo of my yacht in the early stages of construction in the factory you can see how the chain plates to which the shrouds were attached were very securely fixed to the hull and that the two were directly in-line with one another thus minimising bending forces on the hull. That contrasts with methods using deck-mounted attachments where the loads have to be transmitted across a flat section of deck requiring support from stiffening brackets and with the attachments obstructing crew access along the deck past the shrouds. The advantage of the latter method is that foresails can be cut and set a little flatter for higher speed upwind but that was of lower priority for me than strength and easy access.

“Tuning” is often done by a specialist rigger as the end result needs to be a straight and vertically upright mast that doesn’t pull off the fixed rigging connections or distort the hull, even when strong sideways forces from the sails are trying to tear away the mast and rigging. I certainly needed to watch a skilled craftsman in the early years and only felt competent to do the tuning myself much later in my sailing career.

Co-incidentally, in this photograph you can see the very effective electrical “ground system” mentioned in the next article about equipment choices. That was created by attaching wide copper strips around the hull to which the “earth” wire of all electrical appliances were connected. The low-resistance route thus provided to the “ground plate’ mounted externally on the hull resulted in any accidental discharge of electricity into the water instead of though the body of the person operating the appliance.

To Be Continued…

© Ancient Mariner 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player