Introduction

In the comments to my recent article about the Conques Tympanum quite a few readers made reference to ‘Cathar Country’ so, as I have pictures from my trips to the region I thought an illustrated article about the Cathars and the area that now bears their name might be of interest.

From the outset I should make it clear that this brief article is intended neither as an in-depth historical account nor as an academic critique of a long dead religious movement. Rather, it is intended as a brief introduction to the topic of Catharism as well as an illustrated guide to what I consider to be perhaps the most spectacular and photogenic examples of military architecture in the region. There are others, some of which like Montségur, Puilaurens, Lastours and Foix I have also visited, but Carcassonne, Quéribus and Peyrepartuse are my personal favourites. If I can encourage readers who are unfamiliar with the region to put Les Châteaux du Pays Cathare on their ‘places to visit’ list or if I can pique their interest in the topic then I will have achieved my principal objective.

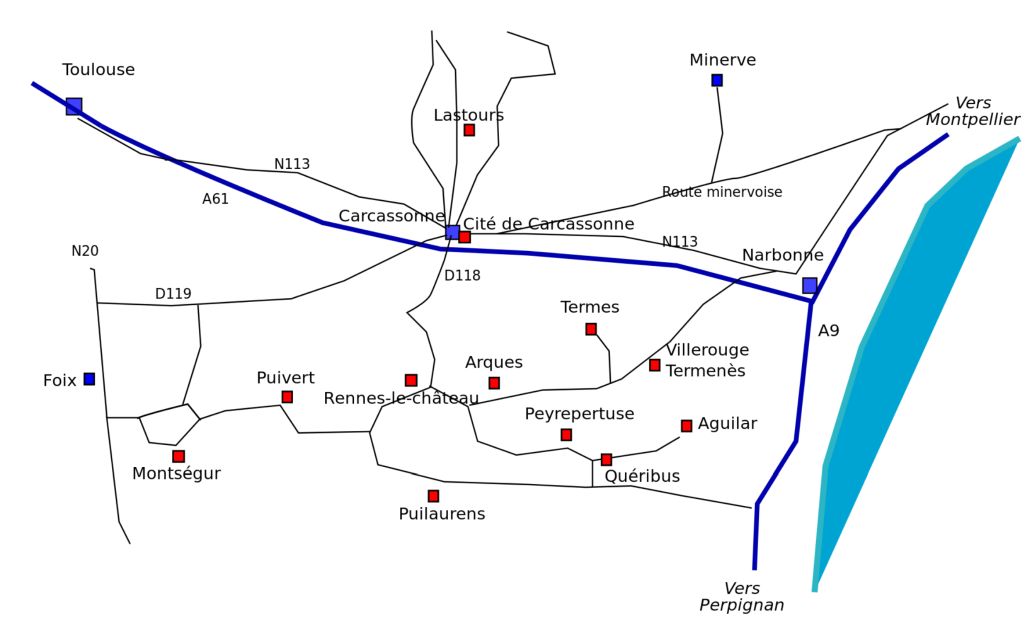

‘Cathar Country’ is a relatively modern term used, or so the more cynical might suggest, to encourage tourism within the Aude region of Southern France around its ancient border with the Kingdom of Aragon. Some of the so called ‘Cathar Castles’ were in fact built by local lords and in their current form date from a later period.

CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5929

What is Catharism?

The origins of the Cathar faith would appear to lie in the Byzantine Empire from whence it spread via trade routes. Scholars believe that Catharism did not appear as an identifiable theology until around 1143 when it was noted in Germany, Northern Italy and France. The religion became particularly well established in the Languedoc region around Albi and at the time followers of the religion were often referred to as ‘Albigenses’.

The word ‘Cathar’ is Greek in origin meaning unpolluted or pure so the term ‘Cathars’ might best be translated as ‘pure ones’ although this description does not appear to have been used by the adherents of the religion who referred to themselves simply as Bons Chrétiens (Good Christians), Bons Hommes (Good Men) and Bonnes Femmes (Good Women.) As opposed to the Catholic doctrine of monotheism (one God), the Cathars believed in Christian dualism, that is that there were two Gods, one evil and the other good. The God of the Old Testament was believed to have created all things that were evil in the physical world, including mankind, and this God they identified as Satan; the other God was the spiritual God of the New Testament. Life was therefore seen as a constant conflict between these two deities with humans, who were really angels, condemned to live in the malevolent God’s material realm from which they could only escape by renouncing material things and regaining their angelic nature by aspiring to become parfait or perfect. Accordingly, the Cathars worshipped the benevolent God who was responsible for the message of Jesus whose teachings they endeavoured to follow. As a result of this, Cathars were ascetic and tended to cut themselves off from others in order to remain unpolluted by outside influences.

As Cathar practices contradicted the way the Catholic church operated, they were considered to be a threat to the established church. For example, the Cathars believed that everyone should be able to read the Bible in their own language, something that did not happen in England until 1537 during the reign of King Henry VIII. In 1229, The Synod of Toulouse condemned such translations and forbade lay people from owning a Bible.

Inquisitor Bernard Gui gives a good summary of the Cathar position, of which this is a portion:

In the first place, they usually say of themselves that they are good Christians, who do not swear, or lie, or speak evil of others; that they do not kill any man or animal, nor anything having the breath of life, and that they hold the faith of the Lord Jesus Christ and his gospel as the apostles taught. They assert that they occupy the place of the apostles, and that, on account of the above-mentioned things, they of the Roman Church, namely the prelates, clerks, and monks, and especially the inquisitors of heresy persecute them and call them heretics, although they are good men and good Christians.

Cline, Austin. “Cathars & Albigenses: What Was Catharism?” Learn Religions, Feb. 11, 2020, learnreligions.com/cathars-and-albigenses-249504.

The Albigensian Crusade

In 1208 papal legate Peter de Castelnau was murdered as he was returning to Rome by a knight thought to be in the employ of the excommunicated Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, the leader of the Cathar opposition. After failing to convert the rebel Cathars back to Catholicism by peaceful means, Pope Innocent III called a formal crusade. As neither King Philip of France nor his son were available to lead the campaign some of his barons, notably Simon de Montfort, were authorised to participate in the 20 years of carnage that were to follow. The Pope had decreed that the lands of the Cathars and their supporters could be confiscated and this led to many northern barons heading south to join the crusade with the objective of enlarging their fiefdoms and hence their personal wealth.

The first objective of the crusade was to take the lands of the Trencavel, lords of Carcassonne, Béziers, Albi and Razes. Carcassonne soon fell as a result of lack of water and treachery and Raymond Roger Trencavel was incarcerated in his own citadel where he died (or was murdered) three months later.

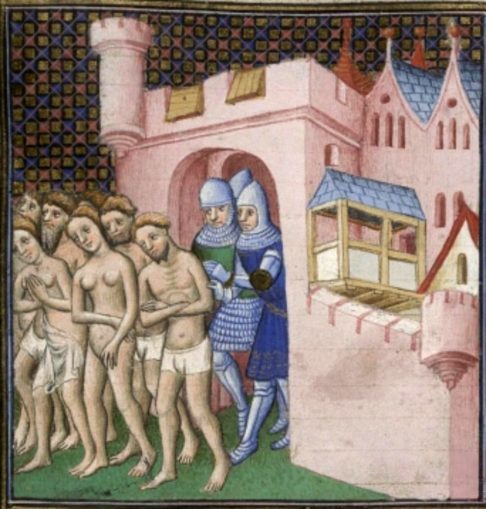

With the army under the spiritual and military command of papal legate Arnaud-Amaury Abbot of Citeaux, Béziers was besieged in July 1209 with many Catholic occupants refusing the offer of safe passage and electing to stay and fight with the Cathars. Writing 30 years later, a Dominican monk recalled that following the taking of the city, Arnaud-Amaury had been asked how to tell Cathars from Catholics replying ‘Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius‘ – “Kill them all, the Lord will recognise his own.” The doors of the church where many had taken refuge were broken down and all the refugees inside (reportedly 7,000 men, women and children) were slaughtered but many more people were killed and maimed as troops rampaged throughout the town. Arnaud-Amaury wrote to the Pope Innocent III, “Today, Your Holiness, 20,000 heretics were put to the sword regardless of rank, age or sex.”

Following the siege of Carcassonne, de Montfort was appointed head of the Crusader army. He was killed in 1218 while besieging Toulouse.

Persecution and Annihilation of the Cathars

The crusade officially ended in 1229 but some Cathars had survived and so were now pursued by the Catholics. An Inquisition was established in 1233 successfully forcing the remaining Cathars underground with any who refused to recant being hanged or burnt at the stake. In March 1244 more than 200 Cathar Perfects were burnt at the foot of Montségur castle in a huge bonfire, the site of which is now known as ‘prat dels cremats,‘ the field of the burned. The last known Cathar Perfect was executed in 1231.

Carcassonne

In 1240 the citadel was again subjected to siege when Trencavel’s son came to attack the northern barons who had taken possession of it. Although the attack was unsuccessful, St Louis reinforced the defences substantially by erecting an outer wall around the existing wall with demilune outworks known as ‘barbicans’ flanked by towers around the entrances to the city. From 1270-1285 the defences were further strengthened by Philip the Bold, the son of St Louis, who levelled the areas between the walls that were known as the ‘lists’.

Under royal government, the citadel had become impregnable and when the Black Prince, son of Edward III of England laid waste to the area during the Hundred Years War, he bypassed the fortifications and instead burnt down the Lower Town that lay outside the walls.

Carcassonne’s importance declined when the Pyrenean Treaty of November 1659 redrew the frontier between France and Spain to the north of the Pyrenees. The city rapidly fell into disrepair and in 1806 it was removed from the list of fortified towns followed in 1850 by its removal from the list of ancient monuments. As a result of pressure from the municipality and the Societé des Arts et Sciences the Citadel was returned to the control of the Ministry of Defence and reclassified as a fortified town. Prosper Mérimée, when he became Inspector General of Ancient Monuments appealed to Paris and in 1853 the architect Viollet-le-Duc was engaged to carry out restoration work and consolidation of the towers and ramparts. Viollet-le-Duc has been accused by some of creating a fantasy version of a medieval citadel which is perhaps unfair as without his enthusiasm, this unique monument would not have survived as the beautiful, historic tourist attraction that we see today.

If you have never visited Carcassonne yet somehow it appears familiar, you may be recalling the hilarious scenes in ‘Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves’ (1991) where the geographically challenged Robin (Kevin Costner) and his sidekick Azeem (Morgan Freeman) ride from The Seven Sisters in East Sussex, via Hadrian’s Wall in Northumbria to Nottingham which is beautifully played by Carcassonne.

Visiting Carcassonne

Carcassonne, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a deservedly popular attraction which during the tourist season can be a frustrating place to visit due to the crowds of visitors. Tour buses full of people from all over the world disgorge their passengers who then wander, apparently aimlessly, around the ancient, narrow streets that are crammed with eating establishments and shops selling souvenir tat. If you are able to visit out of season it really repays the effort and the city is then a delight to explore and photograph. A guided tour is well worth the outlay. We stayed for three nights at a campsite by a little river just outside the city walls but I wouldn’t recommend it as it was noisy and security there was very lax. The chain link fences had been cut and shoddily repaired and we saw local youths climbing in with impunity. Unsurprisingly, theft from tents was said to be a major problem so it is to be hoped that security has since been improved. If you are camping or caravanning, a better plan would be to stay at a campsite of your choice some distance from the city and motor in for the day.

In Part 2 we will look at two of the most spectacularly situated castles in the region – Quéribus and Peyrepertuse.

© text & images except where shown Tom Pudding 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player