© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2020

Arriving at the border town of Irun, in the northern Pyrenees, there is always a bit of a scramble. A change of rail gauge means a change of train. Our connection was the overnight service to Madrid. It was dark by now. En route was the briefest of passport controls and most negligent of customs checks.

Myself and Tammy reserved a compartment for ourselves, and ourselves only, by sliding doors closed and pulling blinds down. We laid on opposite seats with our respective packs (mine small, hers large) in the luggage rack. It was a while before departure. The contact was going just fine. Over another bottle of wine, it might even become a special relationship. Tammy kindly offered to pay. I folded her notes in my palm as I stood, observing, “I need someone to help me carry the bottle.”

Our luggage would be safe unattended, this wasn’t inner-city New Jersey. She tapped her bottom. She had a “bum bag” for her valuables. We left the station to find a taverna.

Decades ago, in the middle of the night, in a rough area next to the railway line, Irun didn’t present its most handsome aspect. Street lights were few, roads were deserted and made of rubble and potholes. In the distance, music and shouting drew us towards the bars. We walked in step, shoulders touching, side by side, bumping into each other.

“Have you got it?” I whispered to her.

“Yes,” she whispered back.

“Let me see,” I replied.

“Not yet.”

Wine patrol continued in silence. Much of the land was scruff or rough ground. Compared to our own compartment on the night train to Madrid, it was an unlikely place for romance.

We arrived at the Bar Bravo, the first in a row of similar establishments. Outside, deserted tables sat in darkness. An open frontage showed more tables inside, drunks slumped across them. No women were allowed. A television on a wall bracket blared in competition with a battered jukebox. The barman was a rough-looking man, unshaven. He stood beside a chained Alsatian. I returned to a waiting Tammy, having relieved the premises of a remarkably decent bottle of two hundred pesos wine, uncorked.

We tiptoed back through the dark and pockmarked streets, followed by a stray dog. At least it kept the rats away. Or rather it didn’t, Tammy screamed. We continued our whispered conversation.

“Why can’t I see it?” I asked her, concerned.

“It’s on the train,” she replied.

“Is that wise?” I’d assumed that she have it concealed about her, perhaps squeezed into that bum bag.

“It’s safe,” she reassured me.

I referenced some of her bizarre luggage, “In the toaster? In a hollowed-out Dr Who book? Can that be done?”

She snorted, “Don’t be silly, it’s wrapped in a towel. It looks very ordinary. Hiding it would just make it look suspicious.”

“I have to see it. We’re wasting our time without it.”

She screamed again as another big rat ran past. Collecting her composure she continued, “You’ll be the first to see it. As soon as we get back to the railroad.”

She took a swig from the wine bottle and then passed it to me. At least there was the hint of a promise of a possibility of a romance on the overnight train. Wrong again. The platforms were packed, mainly with soldiers. Spain is one of these places that only defends itself on certain weeks of the year. A garrison was heading home to their mother’s cooking.

In the throng, our train seemed a hundred identical carriages long. We stood for a moment. The adrenalin, leaking from other places, drained back into my brain and eyes. I found my bearings. Tammy held onto my hand. I pulled her through the uniforms towards our compartment. At least she wasn’t trying to escape.

Closing the doors and windows and pulling down the blinds hadn’t worked. Our compartment was occupied. We jammed into the corner seats, opposite each other, next to the window, underneath our luggage. We could but smile, chat and share the wine. As the train jerked to life and crawled further into Spain, our companions stirred. A mandolin appeared. Good singers cleared their throats. Drinks and snacks were passed around. The Spanish army are very good company on a date. Even as fifteen jammed into one compartment, some making themselves comfortable for the night in the luggage rack.

Tammy could be razor-sharp and very quick-witted. In equal measure, for the entertainment of the people, she could also be hilariously dumb. She told us all about Newark, New Jersey.

“We don’t have kilometres, we have inches.”

“The mosquitoes are so big they land at the airport.”

“The ‘roaches are so big we can ride them into town.”

It was a ploy that all fell victim to. Everybody fell in love with her, with us. Another ploy, was to excuse herself to the restroom and come back having, a little bit too obviously, taken her bra off. She topped that by removing her sports shoes and socks, putting her bare feet on my lap and asking for a foot massage. She invited me to do the same. She untied my laces as if buttons on a shirt, peeled off my socks as if underwear, pulled the material between finger and thumb. We listened to the mandolin accompanied Spanish army conscript choir. We played with each other’s dirty toes. A bottle of wine sloshed through our veins. It was the best date ever. Like two lost sailors on a plank, rough seas untimely turned to calm after a shipwreck, we fell asleep.

***

I awoke to a bright morning. We were crawling through the environs of Madrid. The regiment had dispersed during a hundred and one overnight stops. Myself and Tammy were alone, she still asleep. She was curled along the seats opposite, foetal. I put some of my clothes on top her to keep her warm and looked out of the window. Eventually, we arrived, rattling, under the giant concrete corrugated roof of Madrid Chamartin terminus.

Early commuters just beginning to arrive from the suburbs, the platforms were neither busy nor not busy.

I woke Tammy, in the gentlemanly way, shaking the seat beside her head without touching her. She was a quick waker-upper. We were soon packed and on the move.

There were washrooms at Chamartin, a Godsend for the long-distance traveller. We would share a shower. Why not? She could show me that package, concealed in her towel. We were soldiers in a war. We would scrub each other’s backs in a steaming hot ducha, like squaddies in a trench sharing a bucket dirty of water. It would be good for morale. It didn’t work like that, there were separate rooms of shower cubicles for separate sexes. Separately refreshed, we rendezvoused at a taxi rank twenty minutes later.

On a brighter note, we had entered the zone where Uncle Sam was organising the transport. Looking out of the taxi window, Tammy noticed much that could be pointed at and labelled, “Gee”. Everything exceptionally different from Newark, New Jersey, could be further observed as, “Gee, that’s neat”. I had to agree. It was my first time in Madrid. I admired the squares, fountains and great buildings, as she did. We were both surprised at the prosperity of the place, not long after the Generalissimo had died and a while before Spain had joined “The Europe”.

Tammy was in charge of accommodations too and Uncle Sam was paying. I recalled that Conrad Hilton was an American. Was there a Randall Hyatt? There might have been.

Taxi now stationary, on a wide, tree-lined boulevard, we piled out. The American taxpayer paid off the driver. Tammy knew where we were. As a courtesy, I offered to swap packs. Her’s was so big that I gasped as I swung it across my back. Mine was so light that Tammy was able to carry it in one hand as if an accessory. She led the way. A big, comfortable, free double bed, a deep bath and a giant breakfast awaited.

Tammy led me into a side street. There’s such a thing as a “Holliday Inn”. They have a good reputation. Then, up an alleyway, alarm bells begin to ring. Motel Seven? Better than nothing. We turned again, down a passageway so narrow that we had to walk in single file. At least we’d have a room and a bed. In terms of morale, the smaller the bed the better. She took me into a tenement building. We climbed some stairs, and then some more, until we reached a landing. Morale plummeted. My Spanish isn’t great but I can translate “Nun’s Hostel”. Morale hit rock bottom, small writing beneath translated to “For Young Women”. On the opposite side of the landing was the brother’s hostel for young men. Morale reached minus two hundred and seventy-three degrees.

“The nuns and brothers are really neat,” Tammy assured me.

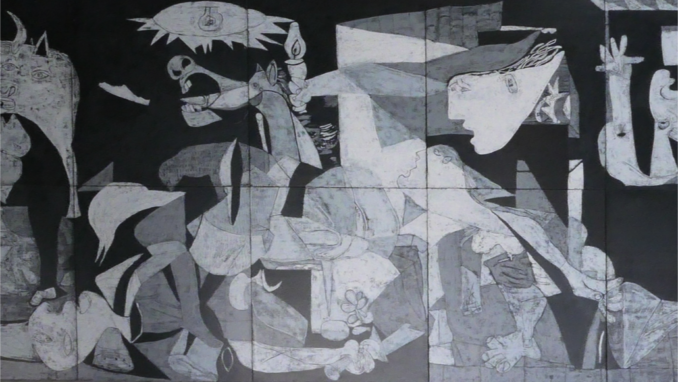

Guernica City Hall Pforzheim (Germany)., Moleskine – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

With our luggage safely in our separate rooms, we struck out for a day’s sightseeing. She wore a long skirt and a dark top. We’d be visiting churches and galleries. She carried a compact Japanese camera. Brunch was at an American style fast food restaurant, early evening snack was in a street cafe. In between times, we had a sandwich outside a palace, next to a park. She loaned her camera to a stranger, who took our photograph as we gazed through the railings. We visited Sol. Before that, she was determined to see the Prado. Within those walls, everything was ‘neat’.

“That’s neat.”

“It’s Guernica.”

“Neat.”

“From the Spanish Civil War. Bombing of civilians.”

“Gee.”

“Picasso.”

“Neat.”

I read a long passage from the catalogue, regarding the horrors of war and the brutalist creative response to it.

“Gee, that’s neat.”

We moved on.

“Goya,” I announced, feeling pleased with myself.

“The Garden of Earthly Delights,” she replied in a contradictory tone. She looked at me. Her head was tilted to one side, mousy hair highlights, bright teeth. A preppy smile admonished me while white sports shoes peeped out from under a pleated tan skirt.

“It’s by Goya, not called Goya,” I replied. It wasn’t. I was on the wrong page.

Between galleries, Tammy had turned a page too, from dumb to razor-sharp.

“It’s by Hieronymus Bosch,” she corrected me.

“What can you see?” She asked.

“Left to right. God, Adam and Eve in a garden of Eden divine. In the centre, a fallen world, distracted people, naked, seeking pleasure. To the right, the consequence; hell, fire, damnation, suffering eternal. A moral world as it was five hundred years ago.”

“And as it is now,” she observed.

We stood and stared.

“Where are we on there?”, I whispered.

“You and I?”, she whispered back.

I nodded.

There was a long silence. I couldn’t help but look at the naked flesh, not least imagining it as hers and mine. Tammy reminded me of our higher purpose, sightseeing being but our earthly fig leaf.

“We’re God,” she announced, “We judge and we bring retribution.”

To be continued …….

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file