British official photographer / Public domain

A couple of years ago I wrote an article here concerning the design of the Spitfire and questioned its status as the best fighter of WWII. I mentioned in that article a follow up piece to explain my views on what could and should have been developed in its stead. This article sets the scene for the design of what should have been flying in the Battle of Britain and further.

When designing anything for a client one must strive to design what is needed to do the job intended. The client will tell you what he wants, that is not the same as what he needs.

When acquiring aircraft, the RAF, or its forerunner, the Royal Flying Corps, buy what they think they want. This has often led to a mediocre end result, Designers who see what is needed and design accordingly have pulled the fat from the fire time and time again.

Two wartime examples of what was needed are the Blenheim Bomber and the Mosquito, both built as private ventures. Two examples of what the RAF wanted are the Fairey Battle light bomber of 1936 (2,200 produced for no gain whatsoever) and the Boulton Paul Defiant of 1935, a turret fighter (of which about 1,000 were built for very limited effect).This was a huge waste of resources at a time when every bomber and fighter was needed, in effect over 3,000 sitting duck targets were produced and many aircrew lost.

Back in WWI, when aircraft design was in its infancy, the biplane was the accepted type of aeroplane; A monoplane, a single wing, can be constructed to take the loads but will be either complicated to build and/or heavier. In engineering terms the wing can be a single heavy beam or a composite beam which is formed by two lighter beams placed further apart. Early monoplanes were either too heavy or too fragile or, indeed, both and in 1912 the RFC decreed that all of their future designs would be biplanes. The order was rescinded quite soon afterwards but generally designers played safe and stuck with developing the biplane. In about 1925 the RAF decreed that all of their aircraft would be ‘all metal’, this would be ‘modern’ and, of course by their reckoning, better.. Disastrous decisions of this type are traditional in Britain, later we had the ‘all metal monoplane’ , later still we had the ‘all jet’, then ‘all supersonic’, the ‘all unmanned missile’ and then next the ‘all collaborative’ decisions to stifle design, and deny designers the freedom to innovate. Some outstanding planes have been built that defied each of these pronouncements which was just as well, what was needed was quite different to what the RAF thought they wanted when wars broke out.

In 1932 an enterprising chap named F G Miles, (known even to his family as ‘Miles’ which gets confusing when his brother George joined the company) was earning a living, building and repairing aircraft at Shoreham and teaching people to fly. Flying was a popular thing among the bright young things or the era, he managed during his teaching to charm one of his clients who, with her husband, was purchasing a plane, She later divorced her husband and married him. The lady, ‘Blossom’ Miles was attractive, rich, well connected and clever. She was a mathematician and contributed to the design process by doing stress calculations and acting as draughtswoman. She later set up and ran the training school for the company that grew from the commercial success of this original aircraft.

The aircraft they designed together was The Satyr, an acrobatic single seat biplane, it performed well but Miles knew that the monoplane was the future and they set about designing one and finding someone to build it. They formed a partnership with a car dealer and builder of aircraft at Woodley Airfield near Reading, Charles Powis, who traded under the name of Philip and Powis.

This first aeroplane was The Hawk, a monoplane of all wooden construction. It was built in 1933 by one craftsman with a 14 year old apprentice with hands on help from the design team. F G Miles as chief engineer and part time builder and Blossom as draughtswoman and part time builder. The Hawk was powered by 95 hp ADC Cirrus IIIA engine which was bought cheaply from an agent who had been left with a stock of them. The engine was ‘half’ of a Renault V8 which powered some WWI planes. A cheap reliable engine, aerodynamically clean design and the cheapness of building in wood rather than metal meant that he could sell a plane with good performance for under £400, a price well below any rival aircraft. The Miles Hawk was two seater with fixed undercarriage, an open cockpit design which had good handling, low landing speed and was well suited to the job of teaching people to fly and many were bought for that purpose.

Not by the RAF though, here we have an example of official attitudes, they wanted safe biplanes, they wanted all metal planes. Miles knew that they needed monoplane trainers of the same monoplane configuration as the monoplane aircraft that Miles knew they needed to pilot when fighting. They also needed them to be built cheaply and quickly which meant building in wood. This was the first of many occasions when Miles knew what the RAF needed and months and years were wasted waiting for the RAF types to realise that they were wrong. Over the years the Hawk had been fitted with more powerful engines, had been built in various seat configurations and had been successful in air races popular at the time. One variant was the Hawk Trainer with a slightly wider fuselage to accommodate RAF service equipment that Miles knew would needed, in 1936 the RAF were backed into a corner with war on the horizon and pilots for the new generation of monoplane aircraft were chugging around in Tiger Moth biplanes.

Daventry B J (Mr), Royal Air Force official photographer / Public domain

The RAF finally ordered a development of the Hawk which was given the name of the ‘Miles Magister’. The first low wing monoplane trainer to be bought by the RAF, and significantly, a wooden aircraft which was in contravention of their ‘all metal’ ruling. It did sterling service as a basic trainer by introducing pilots to the handling characteristics of the monoplanes they were to fly when qualified. About 1,300 of this basic trainer were built.

Miles was, as usual, one step ahead and was already working on what the RAF needed as an advanced trainer, it was good that they now wanted the Magister but events were moving on and what they now needed was something faster, with enclosed cockpit, retractable undercarriage and performance far closer to the anticipated 300 plus mph of the aircraft now reaching service.

With no official backing, as a private venture, Miles and his team set to designing and building the aeroplane the RAF didn’t realise they needed. In just a year the small team of no more than eight workers at any time designed and build a good looking, aerodynamically ‘clean’ wooden aircraft and fly it.

(A plane produced in metal, the Spitfire took 24 men to design and took two and a half years to get to first flight).

The plane was powered by a 745 hp Rolls Royce Kestrel engine, as used in many biplanes in RAF service at the time. In 1937 it took to the skies and astounded the audience at an air show by showing off its speed of 296 mph, just short of the 310 mph top speed of the Hurricane at that time . The Hurricane was of course equipped with the more powerful 1,030 hp Merlin, an impressive result. The RAF however were not impressed, they didn’t want a plane like that, it was, apparently ‘too advanced’ and was ‘premature’. So the M 9 Kestrel trainer, which set a record for speed for a two seater plane of that power, was unloved and unwanted by the RAF. They instead ordered the DeHavilland Don, that company had gone along with the ‘wants’ of the RAF instead of the ‘needs’ and had designed a camel of an aircraft to train, not just pilots, but navigator and turret gunners as well. The result was the abysmal failure that Miles had known it would be.

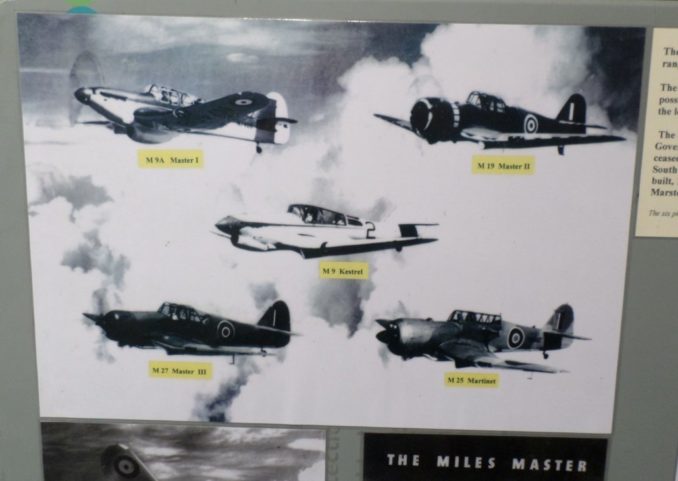

The RAF then grudgingly, in June 1938, ordered the Master1 M 9A which was a ‘de-rated’ development of the Kestrel. It was to have a lower powered Kestrel engine, a modified cockpit, a strengthened fuselage and the radiator and scoop repositioned from under nose to a ventral position under the cockpit. These modifications lowered the top speed by about 70 mph but the trainee pilots now have a trainer with speed and manoeuvrability similar to the planes they would fly in anger.

To cope with the large order the Miles company designed and installed the first moving production line for aircraft in the UK, a line that moved on each four hours until a finished aircraft arrived at the end.

The design was originally to use new Kestrel engines, Rolls Royce bought into the company as it was eager to continue the production run which was likely to end as the new fighters would use the Merlin. As Hawker Harts, Hinds and other obsolete biplane aircraft that used this engine were being withdrawn and scrapped the RAF decided to recondition the old engines and run them de-rated to increase service life. They claimed to have a large supply of the engines, later they came back to the Miles Company to admit that they hadn’t got too many after all so would they redesign to take the Bristol Mercury radial engine that was in production for the Bristol Blenheim. Another mark of Master was born, the Master II with a tubbier engine but with more power and an increased top speed..

In true RAF style they later admitted that they hadn’t got enough of those either so could they please have a Mark III with the Prat and Whitney Wasp Twin Junior radial engine which was available as some were made to a French order and obviously not now needed by them. Later the RAF ‘found’ engines that they previously ‘didn’t have’ so there is some confusion what model was built and when. In all about 3,250 of all models of the Master were built.

It is a measure of the convenience of building in wood that these modifications were made without stopping production.

Later in the war the RAF were running out of target tugs, obsolete planes used to tow a fabric streamer targets, and also needed the targets to be towed faster to more accurately mimic combat conditions. They approached the company to ask how long it would take to modify a standard Master to suit, this would involve modifying the rear of the fuselage and the base of the rudder; on hearing ‘a week’ the RAF were amazed as they thought it would take three months. It was ready in five days. This version was developed into the Miles M.25 Martinet of which 1,724 were produced to do stalwart service for years with the RAF, Fleet Air Arm and many foreign air forces.

At the time of the ‘Munich Crisis’, Miles was of the opinion that the RAF needed a fighter that they didn’t want, and quickly too, and he pressed on with the development of the Kestrel engined M9 into a six gun fighter, out came the dual controls and associated second pilot equipment and in went Browning 303 machine guns, gun sights, radios, armoured glass windscreen etc. Twenty four examples were built and used for advanced training but none saw combat.

Miles was convinced that the RAF needed a wooden emergency fighter based on this Master fighter but developed to simplify construction even more and to carry much more punch. Thinking big, he had in mind, not eight but a twelve gun fighter with greatly increased ammunition capacity and far more range than that of the two front line fighters, the Hurricane and Spitfire..

This would be the M20 Emergency fighter the design of which will form the next articles in this series.

Footnote

For those of you wondering where you’ve heard the name Woodley Aerodrome mentioned, it was where, in 1931, Douglas Bader paid a heavy price for showing off in a Bristol Bulldog.

Research material

Miles Aircraft – The Early Years – The Story of F G Miles and his Aeroplanes 1925-1939

Miles Aircraft – The Wartime Years Production, Research & Development, During World War II

The Book of Miles Aircraft A H Lukins

Wings over Woodley Julian Temple

Miles Aircraft The Archive Photographs Series Rod Simpson

Aircraft of the Fighting Powers Vol 2 Harborough Publishing 1942

The Museum of Berkshire Aviation. Woodley

© GrumpyAngler 2020

Audio file

Audio Player