Published by Quill, an imprint of William Morrow & Co. 1988 paperback edition (first published 1987)

ISBN 0-688-07951-2

Internet Archive Book Images [No restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons

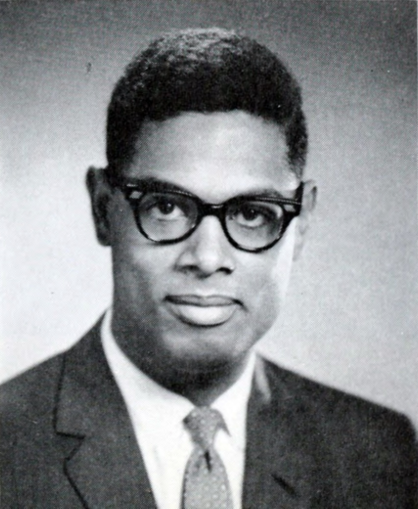

Having reflected on how often he had encountered the concept of ‘visions’ in his work over the years, Thomas Sowell decided to examine their social impact. The result was A Conflict of Visions. The book is one of Sowell’s most significant works and has influenced liberal and conservative writers respectively, like Steven Pinker in The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature and Jonathan Haidt in The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, whose books also look at the major ideological divides that shape political discourse.

Despite being written over three decades ago, Sowell’s book resonates in the current political climate. In the age of Brexit, Trump, national populism generally, social justice, climate change, globalism, etc., when we look at the divides that exist, we can see patterns and instances of behaviour on both sides that are reflective of two visions which have existed for centuries.

Although this is a book review, it is also a discussion of the issues raised therein and a reflection on some contemporary political issues that demonstrate why the book remains so relevant. As with the book, this review is not an attempt to reach solutions to these problems – Sowell indicates that such divides, having existed between the two visions for centuries, are here to stay – but is an attempt to increase understanding.

Anyone acquainted with Sowell’s work knows he has distinct views on economics, politics, and a number of other matters. In most of his other books his own perspective is clear in his narration but in A Conflict of Visions he resists any temptation to display bias, instead writing impartially and providing a fair and balanced discussion of the opposing visions in order to understand where they come from. Successfully doing this is in itself no small achievement.

As Sowell indicates, visions, which arise from contending interests, although understood clearly enough by the parties directly involved, might be little understood or cared about by the general public – partly due to deliberately confusing propaganda issued by the parties – even though the public are the ones most impacted upon by said visions.

Visions are not merely emotional – they are logical. They are not limited to ideologues – they can shape the thoughts of anyone. They exist in moral, political, economic, religious and social spheres. We can sacrifice all for them and their conflicts can tear society apart. These divides are not just recent; they have a long history.

The book is divided into two parts and consequently so is this review. In the first part, Sowell looks at patterns, which we will examine here, though contemporary examples will be used to illustrate them. In the second part, Sowell discusses applications, which we will look at next time.

[Note: Spellings and punctuation in any quotations are taken directly from the book and are thus in the American form. Italics in the quotations are also as presented in the book.]

Part I – Patterns

The role of visions

Sowell begins by observing how often people line up on opposite sides of different political issues which might not be fundamentally linked. This is no coincidence: these opposing positions stem from different visions of how the world works. Given that reality is complex, such visions might omit certain information, making it easier to reach our goals but the danger is that we can then confuse them with reality itself.

Visions give us a sense of how the world works and we can build theories upon them. Sowell sees people as generally adhering to one of two visions, which he calls ‘the constrained vision’ and ‘the unconstrained vision’.

Tracing the constrained vision back to the likes of Adam Smith, Edmund Burke and Alexander Hamilton, Sowell shows how such thinkers believed that man’s morality is essentially limited by nature and rather than seeking to change human nature, it is best to seek to produce the greatest benefits in the most efficient way, namely by constraint. Sowell points out that this was seen by Smith, an economist, through what was essentially an economic solution, namely through incentives or trade-offs. It was not from the notion that self-interests equated to the interest of society:

On the contrary, the functioning of the economy and society required each individual to do things for other people; it was simply the motivation behind these acts – whether moral or economic – which was ultimately self-centred. [p. 23]

In the unconstrained vision, the contrasting view, going back to Smith’s time, can be found in the work of William Godwin and the Marquis de Condorcet. According to Sowell:

Godwin regarded the intention to benefit others as being “of the essence of virtue,” and virtue in turn as being the road to human happiness. [p. 23]

This idea viewed that someone could feel the needs of others to be greater than one’s own needs. This didn’t deny that human nature was flawed but took the perspective that it wasn’t set in stone, that it could be changed and that people had the potential to be better. Man, in this view, is essentially “perfectible”.

Godwin had contempt for the idea that incentives were necessary, believing people would do what was right because it was right and Sowell notes that in the long term the goal was to create “a higher sense of social duty” and that incentives would merely inhibit that goal.

In this unconstrained view, also shared by Condorcet, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Stuart Mill (although Mill’s position was more complicated, as we shall see later) human nature was not constrained but rather it was limited by social institutions; sources of dissatisfaction must be caused by wicked intentions or turning a blind eye to attainable solutions.

The great evils of the world – war, poverty, and crime, for example – are seen in completely different terms by those with the constrained and unconstrained visions. If human options are not inherently constrained, then the presence of such repugnant and disastrous phenomena virtually cries out for explanation – and for solutions. But if the limitations and passions of man himself are at the heart of these painful phenomena, then what requires explanation are the ways in which they have been avoided or minimized. [p. 31]

The French Revolution more firmly reflected the unconstrained vision, whilst the American Revolution had a mixed intellectual foundation and although men like Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson similarly to the French, the dominant influence on the Constitution was in the form of the constrained Federalist Papers. A system of checks and balances reflected the view that people could not be trusted with power. Sowell says of the French Revolution:

Even when bitterly disappointed with particular leaders, who were then deposed and executed, believers in this vision did not substantially change their political systems or beliefs, viewing the evil as localized in individuals who had betrayed the revolution. [p. 32]

When looking at the actions of the European Union since the 2016 referendum, we can see they have displayed an increased push towards federalisation – which perhaps indicates, as alluded to on this site previously, that many Remain voters didn’t know what they were voting for – e.g. scrapping the veto of member states on tax policy or the push towards an EU army:

Macron and Merkel now fully back a European army. That’s great news! I explained why we need it at the #ALDECongress in Madrid. Watch my intervention👇 pic.twitter.com/aokTDEx1iY

— Guy Verhofstadt (@guyverhofstadt) November 13, 2018

Coupled with perceptions of arrogance on the part of certain high-profile Remainers, it is unsurprising that some who voted Remain have had pause for thought and have even felt alienated, by those advocates of the cause they previously supported, yet others remain as fervent as ever in seeking to prevent the UK from leaving the EU. This shows how powerful a hold a vision can have; staunch proponents hold the sense that the vision, even if it is damaging, is nonetheless correct, whilst opponents are considered the dangerous ones. This may even seem cult-like to some. Sowell quotes Jefferson as saying of the French Revolution:

“My own affectations have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated.” [p. 34]

This, incidentally, compares uncomfortably closely with comments made by Mao Zedong as quoted by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday in their book Mao: The Unknown Story, particularly one [p. 428] where he said that if war had broken out, he would have been willing to see half the population of the world die if it had led to the end of imperialism and to the world becoming socialist.

Sowell does point out that Jefferson ultimately turned against the French Revolution as casualties continued to a level which he would not in fact accept. (Mao of course had no such qualms.) But some will continue to defend revolutions, or other matters related to visions. For such people, the costs involved in the process are secondary to the overall goal. For the constrained, on the other hand, peace and order in society is paramount.

Visions of knowledge and reason

Sowell states that for the constrained, the knowledge of any individual alone is wholly insufficient for purposes of social decision-making:

A complex society and its progress are therefore possible only because of numerous social arrangements which transmit and coordinate knowledge from a tremendous range of contemporaries, as well as from the even more vast numbers of those from generations past. Knowledge as conceived in the constrained vision is predominantly experience. [p. 40]

But for the unconstrained:

Reason was as paramount in their vision as experience was in the constrained vision. According to Godwin, experience was greatly overrated – “unreasonably magnified,” in his words – compared to reason or to “the general power of a cultivated mind.” Therefore the wisdom of the ages was seen by Godwin as largely the illusions of the ignorant. [p. 43]

This attitude is reflected by some Remainers and Trump opponents who like to emphasise the somewhat sweeping claim that Leavers and Trump supporters are people of lower education, at times even suggesting they are stupid. Such attitudes fit well Godwin’s notion that those who do not have “cultivated minds” are “persons of narrow views”.

For the constrained, it is dangerous for intellectuals to have such a special role in running society:

The central danger… is the intellectuals’ narrow conception of what constitutes knowledge and wisdom… in Burke’s words, “endeavouring to confine the reputation of sense, learning and taste to themselves or their following,” and are capable of “carrying the intolerance of the tongue and the pen into a persecution” of others. Adam Smith spoke of the doctrinaire “man of system” who is “wise in his own conceit” and who “seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board. [p. 47-8]

The superiority of experts within narrow areas was not denied but the idea that this expertise gave them general superiority that superseded more widely dispersed knowledge was.

We see these differences in the law, where the constrained believe that systemic experience provides greater wisdom than any individual or group, but the unconstrained favour law-making through judicial activism and believe their methods are morally and intellectually superior.

Differences exist in social policy too:

The unconstrained vision has tended historically toward creating more equalized economic and social conditions in society, even if the means chosen imply great inequality in the right to decide such issues and choose such means …

… Conversely, those with the constrained vision have tended to be less concerned with promoting economic and social equality, but more concerned with the dangers of an inequality of power, producing an articulate ruling elite of rationalists. [p. 55-6]

Whilst fidelity is highly important to the constrained, sincerity is imperative to the unconstrained:

Sincerity is so central to the unconstrained vision that it is not readily conceded to adversaries, who are often depicted as apologists, if not venal… Even where sincerity is conceded to adversaries, it is often accompanied by references to those adversaries’ “blindness,” “prejudice,” or narrow inability to transcend the status quo. [p. 59]

It is not difficult to see the parallels in the attitudes of certain Remainers, who class Leavers as ‘bigots’; or progressive/liberal types who label those who criticise Islam as ‘Islamophobes’ and ‘racists’; or climate change campaigners who class those who question their orthodoxy as ‘deniers’, etc. These are topical issues but this way of thinking is clearly nothing new.

On the matter of youth and age, a similar conflict arises:

In the constrained vision, where experience is “the least fallible guide of human experience,” the young cannot be compared to the old in wisdom. Adam Smith considered it unbecoming for the young to have the same confidence as the old. “The wisest and most experienced are generally the least credulous,” he said. [p. 62]

By contrast, for the unconstrained, the young are considered to hold great advantages:

Condorcet wrote in the eighteenth century: “A young man now leaving school possesses more real knowledge than the greatest geniuses – not of antiquity, but of the seventeenth century – could have acquired after long study.” In an unconstrained vision, where much of the malaise of the world is due to existing institutions and existing beliefs, those least habituated to those institutions and beliefs are readily seen as especially valuable for making needed social changes. [p. 63]

We see such views reflected today. Remainers, containing a higher proportion of young people, are, they like to remind people, ‘better educated’. For Leavers, this is irrelevant: age and experience bring wisdom the young do not automatically have, regardless of formal education. If a young academic tells an old fisherman of ‘limited education’ that the EU is beneficial to the fisherman because X policy suggests so, the fisherman might not have the academic knowledge to counter with, nor might he have the verbal dexterity to impress those who hold eloquence with words in high regard, but his life experience of the restrictions on his livelihood imposed by EU fishing quotas gives him a more tangible understanding of the impact of EU diktats than an academic could have based on a selective reading of statistics. Such academics don’t appreciate that many people believe they have justification for having become disenchanted with the established order, in the UK as elsewhere. But some intellectuals would rather interpret their views as being based on ignorance, bigotry, oldness, ‘whiteness’ (whatever that is) and lacking the cosmopolitan open-mindedness of the young.

“Children are a sort of raw material put into our hands,” according to Godwin. Their minds “are like a sheet of white paper.” The young were viewed by Godwin as a downtrodden group, but from among them may be found “one of the long-looked-for saviors of the human race.” [p. 63]

We can see parallels with the policies of dictators like Adolf Hitler with the aim of controlling the young, as well as the current media portrayals of climate activist Greta Thunberg as a young prophet of doom warning us to repent and trying to save humanity from its dire fate.

However, the constrained vision… cannot seek prudence in youth, for prudence was regarded as the fruit of experience. Nor was moral fervour a substitute: “It is no excuse for presumptuous ignorance that it is directed by insolent passion,” according to Burke… According to Condorcet, “prejudice and avarice” were characteristics “common to old age.” [p. 63-4]

The portrayal of older people as bigots and Leave campaigners as backed by supposedly nefarious business interests (conveniently ignoring the bigots and the wealthy interests that backed Remain and the arguably infamous ones who have since sought to overturn the referendum result) shows us that Condorcet’s notion of “prejudice and avarice” against the elderly fits well with the thinking of some Remainers. Their entrenchment in their vision and sense of superiority, which they take to be moral as well as intellectual, will not allow them contemplate being wrong. It is unsurprising that Leavers interpret such attitudes as “presumptuous ignorance” if not blind arrogance.

The arrogance and exhibitionism of intellectuals were likewise recurring themes in Burke – along with the dangers that such intellectuals posed to society. He spoke of their “grand theories” to which they “would have heaven and earth to bend.” Hobbes also saw those who “thinke themselves wiser, and abler to govern” as sources of distraction and civil war. [p. 66]

From this perspective, a number or Remainers reflect the unconstrained attitudes of intellectuals and others who believe they know best and who stir up further division and strife. In an echo of Hobbes, it seems as if they are almost craving some kind of civil conflagration – they certainly appear to be inviting it.

Visions of social processes

Esperanto is a language that exhibits why, for those of the constrained vision, languages cannot simply be created; they have to evolve and they can serve a number of purposes this way. The same thinking is applied to markets and as an argument against central planning. Man simply cannot know enough to make such systems work. Burke and Friedrich Hayek reflected this view.

For the unconstrained vision, there is no such sense of limitations. If direct control of, say, an economic system is possible, then why seek to get to the end result by a circuitous route? Outright direct control is not always sought, but elements of such thinking persist. Select third parties can agree on what constitutes ‘needs’ or ‘waste’.

There are costs to all social processes. To the unconstrained, like Godwin, we should not be bound by the constraints of decisions made in the past, but the same limitations that he would condemn – loyalty, marriages, constitutions, etc. – would be upheld and revered by those of the constrained view. This divergence of views can particularly have an impact in the area of law:

To knowingly accept injustice is unconscionable in the unconstrained vision. But in the constrained vision, injustices are inevitable, with the only real question being whether there will be more with one process than with another. [p. 79]

The clash of visions also occurs regarding the notion of patriotism:

At the extremes, the constrained vision says, “My country, right or wrong,” while the unconstrained vision casts its exponent in the role of a citizen of the world, ready to oppose his own country, in words or actions, whenever he sees fit. Patriotism and treason thus become a meaningless distinction at the extremes of the unconstrained vision, while this distinction is one of the most central and most powerful distinctions in the constrained vision. [p. 81]

Today’s Leavers and Remainers reflect this, as do nationalists and globalists, et al. Patriotism, a matter of great pride to Leavers, appears of far less importance to Remainers and might even represent something backward and primitive to many of them. This might well explain why they have had little hesitation in undermining the UK’s negotiating position. The philosopher and stanch Remainer A. C. Grayling actively encouraged the EU to drive such a hard bargain that it might force the UK to reconsider leaving:

This attitude has been particularly prevalent in the UK Parliament. Dominic Grieve MP, having stood on a Tory manifesto in 2017 to deliver Brexit and having said the same year that Parliament should not fetter the Government, had by 2018 changed his tone and said that Parliament could direct the Government what to do. The so-called ‘Benn Act‘ effectively made this so. In 2019 Grieve tabled bills calling for a second referendum. On top of a number of meetings with senior EU officials, some Remainer MPs apparently coordinated their efforts with the EU’s legal department. There were claims of collusion with the French government to frustrate the UK’s efforts to leave and then there was the revelation by David Sassoli, president of the European Parliament, that he had been working with Speaker John Bercow to delay and possibly even prevent the UK from leaving the EU.

To Leavers, these sorts of manoeuvres might constitute treasonous behaviour. MPs who have generally attempted to overturn the 2016 referendum are seen by a number of Leavers as ‘traitors’ engaging in ‘betrayal’, however much those MPs might object to such language.

Burke and Hamilton saw the emotional attachments that lead to loyalty as being beneficial social ties, crucial for society, otherwise the alternative would be pure selfishness. But for Godwin, the focus ought to be on reason and the entire human race, with love of one’s country being “a deceitful principle” that built a preference based on “accidental relations, and not upon reason”. Neither vision sees the smaller unit as being more important than the larger but the unconstrained vision believes we can act beyond it, whereas the constrained believes we cannot due to human nature.

… Smith focused on individual behaviour precisely as it conduces indirectly to social benefits – not simply because it benefits the individual…

Those without this constrained vision of human nature equally logically proceed in the opposite way, by demanding an end of nationalism, and an assumption of “social responsibility,” by both individuals and institutions toward one’s fellow human beings, whether at home or overseas. [p. 85]

This difference is illustrated today by the contrast between those who embrace nationalism, with a sense that more cohesive ties and better functioning societies are formed by catering to their own interests, versus those who embrace globalism, favouring open borders and believing we should cater for the problems of the rest of the world.

To the unconstrained, the notion of people being rewarded because of “privilege” is wrong: their skills can be utilised without what the unconstrained would consider to be “unmerited rewards” which have a negative impact on society. But for the constrained, any “injustice” in paying unequal or unmerited rewards is a trade off against the greater injustice of damaging society by not paying enough to incentivise production and use.

These views were particularly reflected in the contrasting Labour and Conservative economic policies of the 1970s and 1980s, especially as regarding taxation, although they remain common today, in the UK and elsewhere.

It is not just in moral judgement but in causation that this difference of views can be seen. For the constrained, incentives – punishments and rewards – must be used, because human nature means people will not behave their best without these factors. But for the unconstrained, human nature is variable and those benefiting from or ignorant of the current social order are the obstacles.

Even the definition of freedom differs between the two outlooks: to the unconstrained, even if there is freedom of action in the process, if the means of achieving one’s goals are lacking, there is no freedom in the result – even if legal constraints are absent, it still cannot be freedom; for the constrained, however, “freedom is defined in terms of process characteristics” and one cannot prescribe results but only initiate processes – equality of results is offensive to equality of process.

Varieties and dynamics of visions

There are differences in degree between the two contrasting visions, as well as inconsistent and hybrid visions.

Sowell notes the religious language used to describe someone who changes their vision – conversion, apostasy, heresy. As an aside, the historian Michael Burleigh in his books Earthly Powers: The Conflict Between Religion & Politics from the French Revolution to the Great War and Sacred Causes: Religion and Politics from the European Dictators to Al Qaeda discusses at length the idea that certain political movements have taken the place of religions and have become ‘political religions’ or ‘secular religions’. Sowell doesn’t go into this topic but his reference to the use of religious language does hint at the significance of the depth of the passions that arouse such strongly-held and almost religious views.

Though there are differences in degree, one can still tell if a vision is constrained or unconstrained by looking at: 1) the locus of discretion and 2) the mode of discretion.

Some ideologies do not fit within either vision. Fascism could be compared with the unconstrained vision in its emphasis on surrogate decision-making, but neither the modes of decision-making nor of choosing a leader are rational and the uses of emotional ties and violence don’t fit that vision.

Marxism is a hybrid vision and this puts it at odds with the rest of the socialist tradition. The Marxist vision of history fits with the constrained pattern and Marx saw the bourgeois regime as a “temporary necessity” in contrast to socialists who believed capitalism to be immoral. However, whilst he believed in inherent constraints, he did not see them as being fixed in human nature – rather they were material and would be removed when science and technology enabled, so in terms of looking forward Marx was unconstrained.

Utilitarianism is another hybrid. Jeremy Bentham was a fan of laissez-faire economics and even expressed the view that Adam Smith did not go far enough in some aspects, but in politics and law Bentham followed the unconstrained pattern. John Stuart Mill too is hard to place in either vision: while he held the unconstrained view that laws are created (as opposed to evolved, as per the constrained vision) he noted that such laws must be in accordance with the traditions and customs of the people, otherwise they will fail. He also said that income distribution was not constrained but the consequences of particular rules of distribution were “beyond man’s control”. Mill often spoke in unconstrained terms but qualified what he said with provisos more in keeping with the constrained vision.

There are also a number of noteworthy features of the two main visions which, nevertheless, do not define them. Instead:

What is at the heart of the difference between them is the question as to whether human capabilities or potential permit social decisions to be made collectively through the articulated rationality of surrogates, so as to produce the specific social results desired. [p. 112]

In the unconstrained vision, the locus of discretion rests with the surrogate decision-maker, or ‘expert’. In the constrained vision, “the loci of discretion are virtually as numerous as the population.” What makes a vision is not scope but coherence; consistency between premises and conclusions.

Libertarians also defy easy classification – although they are more associated with constrained figures like Smith and Hayek, they are in some ways closer to unconstrained figures like Godwin when it comes to rationalistic individual conscience or pacifism.

Even Godwin didn’t feel the need for government to destroy private property or have government come in and redistribute as it saw fit, which would put him against general left-wing thinking in this area but he did have a sense of pervasive moral responsibility and believed government redistribution was unnecessary because individuals would eventually voluntarily share on their own.

As Sowell indicates, neither the left-right dichotomy nor the constrained-unconstrained one “turns on the relative importance of the individual’s benefit and the common good.” The common good is paramount for both but the difference is in terms of how it is to be achieved. They make different assumptions regarding human nature and social cause and effect. Complications can exist when looking at this in terms of conservative and liberal differences because these terms can be relative and sometimes they can end up arguing on the ground of the opposing sides, but the conflict of the constrained and unconstrained visions as outlined by Sowell has persisted. Compromises in day-to-day politics are “more in the name of truces than of peace treaties.”

Issues like Brexit, Trump or the wider divide between nationalism and globalism cannot strictly be seen strictly as left-right splits: polling published in the immediate aftermath of the referendum showed that just over a third of people who voted Labour in 2015 and just under a third who voted Liberal Democrat opted to Leave, as did a slightly higher number of Conservative voters wish to Remain. Donald Trump, contrary to attempts by the corporate media and political activists (but then, a la Mark Twain, I repeat myself) to portray him as an extremist, espouses policies that his Democratic opponents were in full agreement with a few years ago, regarding topics such as border security and immigration. Trump has also received support from a number of people who would have traditionally described themselves as Democrat voters. Therefore, such issues fit more within the realm of Sowell’s opposing visions than in left-right terms.

Next time, we will look at the second part of Sowell’s book, where he examines applications of these visions.

Amazon book link:

Amazon author page: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Thomas-Sowell/e/B00J5BK55K

Author’s website: https://tsowell.com

Twitter page (not the author’s own, but it regularly tweets many good Sowell quotes): https://twitter.com/ThomasSowell

© The Black Swan 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file