October 24th, 1809.

We are at Romford in Essex, after a circuitous journey to throw pursuers off the scent. Our coaches crossed London Bridge as if bound for Dover, but instead we soon left the Kent Road and took the Woolwich ferry back across the river. By the time we were back on the north shore it was completely dark and we made little further progress, but at least we are in a place where the authorities are unlikely to find us. The horses will have a chance to rest overnight, and there will be no need to change them until we have gone some way tomorrow.

There is room for only four bears inside each coach, so little Hugh has to sit beside a coachman, muffled in a waterproof cape with a hood. Dolores sits on the other side, her red hair streaming in the wind, so no one on the road notices anything else. Fred and Jem sit outside on the other coach. On each, a guard sits at the rear with a blunderbuss. We could have taken care of that ourselves, but must observe convention.

We are spending the night in a barn outside the town to avoid notice. The coachmen and guards insisted on being put up in an inn, at our expense of course. They have strict orders, sweetened with a modest payment, not to talk about their passengers, and I think they will hold their tongues as it would be to their disadvantage to be known to have aided an escaped prisoner.

October 26th, 1809.

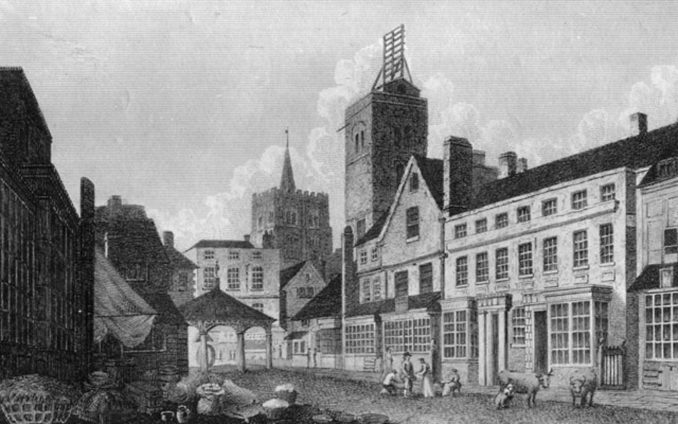

We are in Great Yarmouth, a reasonably elegant town since it is now patronised by the gentry in quest of the sea bathing cure for their excesses. However, since the cold autumn winds have started to blow the fashionable folk are gone, and the place is given over to the Royal Navy, for which it serves as a supply base, and to a large fishing fleet.

It has not been a quick journey, as we have travelled on small roads in bad condition for much of the way. We spent the previous night at Ipswich. The only notable incident during that day was the loss of a wheel near Colchester, but luckily the coach was not overset and the fault was quickly corrected when four bears held up the axle for the wheel to be returned to its place and secured with a new pin. Our destination is the Bugle Inn in the Market Square, the usual stopping place of this coach when visiting Yarmouth.

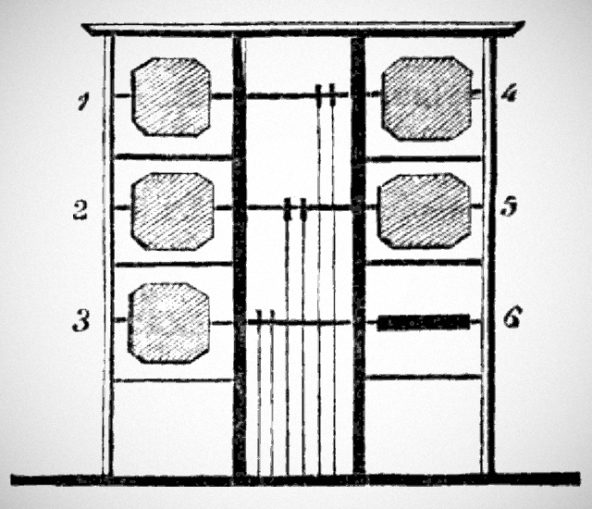

As we approached the town we were disagreeably surprised to see the wooden frames of a naval semaphore telegraph set up along the road, on church towers and on such hills as can be found in this flat countryside. It seems that the line was completed last year, and now a message can pass between London and Yarmouth in minutes. However, it is used only for naval communications, and the civil authorities cannot avail themselves of it except perhaps in the direst emergency. We do not think that Fred’s escape would be counted as such.

This semaphore system was devised by Lord George Murray. It uses six shutters, and can be operated at night by placing lamps behind each of the shutters. Thirty-two different combinations are possible, permitting transmission of all the letters of the alphabet as well as a few extra codes to indicate the start and finish of messages, readiness to send and receive, and the beginning and end of numeric codes.

I consider it unnecessarily complicated, since it would be possible to send messages with a single shutter that could be opened or closed at a constant rate set by identical pendulums in each station. Instead of frantically manipulating all the levers of six shutters, you could simply move one six times.

But while I was musing on such matters, danger presented itself from another direction. We were now in the streets of Yarmouth, and the coach with Fred and Jem travelling outside was at the front, with myself inside. There was a thump, and I saw Fred on the ground and racing away into a side street; a moment later Jem followed him.

A glance out of the window revealed the reason. A squad of Marines was approaching us, muskets at the ready, escorting a sullen rabble of yokels. It was the press gang, exercising their infamous right to seize men from the streets and forcibly enlist them in the navy.

The coachmen and guards, unable to desert their posts, were quickly surrounded, the guards’ blunderbusses of no avail against twenty muskets and the force of an unjust law. They were obliged to descend and join the captive band.

Dolores, of course, was in no danger, though her fury was something to behold. While she raged against the Marines in words that I blush to remember, they were pointing their weapons at little Hugh, disguised in his hooded coat. When he pushed back his hood and they found a small bear staring at them with naked hostility they were amazed, but this was nothing to their astonishment when they forced open the doors of the coaches and found eight more bears. They beat a hasty retreat.

Having lost our coachmen, all we could do was continue to the Bugle, leading the horses as we have no coach-driving skills. Here Dolores explained events to an agent, who was wearily unsurprised – such things seem to happen all too often here – and simply said that he would have to enlist more coachmen and guards, if the press gang had left any, before looking for passengers for the return journey.

Angelina, who had detached herself from the party and followed the scent of Fred and Jem to their hiding place in a timber yard, now came to the inn, and we followed her back to meet them. ‘First thing we got to do,’ said Fred, ‘is to get out o’ this Godforsaken town and on to the water.’

October 27th, 1809.

The first ship to leave Yarmouth is the Wensleydale, bound for St Petersburg with a cargo of port and cheap brass samovars made in Birmingham. She is short-handed. ‘Why not?’ said Fred. ‘I ain’t never bin to Russia, and they does say as ’ow travel broadens the mind.’

Russia must be a fine country for bears, and we were happy to agree. We asked Dolores whether she wanted to travel with us, offering her some money to live on if she stayed. She has decided to come, and we are all delighted – especially Jem. I sense that there is a growing tenderness between them.

The captain, one Gideon Larkspur, had heard of our exploit in bringing a ship from the Bay of Biscay to Portsmouth with a crew of just nine bears, and took us on as able seamen and sea bears without asking for certificates (which we do not have). Dolores is engaged as a cook.

October 29th, 1809.

It is good to be afloat again. Bears may not be born to roam the ocean but, as Plautus says, Mare quidem commune certus est omnibus, The sea is surely common to us all. Fred is now fully recovered from his ordeal, and on our first evening he struck up a merry gavotte on his flute and we all danced. He followed it with a hornpipe in which the sailors joined.

Yesterday a gale blew up, and we astounded the crew with the celerity with which we shortened sail. The samovars, packed in straw in wooden crates, have worked loose, and every time the ship rolls there is an outburst of clattering and clanging in addition to the usual groans, rattles and thumps of a ship at sea.

November 5th, 1809 (October 24th Old Style).

We have arrived in St Petersburg, only to find that we have gained twelve days on our voyage. The Russians still use the old Julian calendar which we in England abandoned in 1752, and for them it is the 24th of October, the day when we were galloping around Essex trying to shake off our pursuers. But in both countries it is Sunday, and we must wait until tomorrow before we can start unloading our cargo.

Having nothing much to do, we went ashore and explored the city. It is laid out on a grand scale: the public buildings are magnificent and the churches ornate to a degree that we in England forgot after the Middle Ages. But when you pass beyond the centre, the fine show vanishes and there is little but wooden shacks, while the broad paved roads dwindle into muddy tracks that soon fade away in the virgin forest.

This suited us well. We found an abandoned and partly ruined cabin and made makeshift repairs to the roof with pine branches. It is already snowing, and a layer of snow on the roof will serve to make it weatherproof for now. There was a stove in good enough order to be used, and we have kindled a merry blaze which keeps us snug and warm.

November 6th, 1809 (October 25th O.S.).

It is the fourth anniversary of my fateful meeting with Lord Byron. How much has changed in this time! I have been a student, a soldier and an impresario, and have gained much experience of life. Αs Solon said, Γηράσκω δ’ ἀιεὶ πολλὰ διδασκόμενος, I grow old ever learning many things.

We spent the day unloading the cargo of the Wensleydale. While the bears hauled crates out of the hold, a cordon of sailors maintained a guard around the growing pile of merchandise to keep out as best they could the hordes of scallywags and ragamuffins eager to snatch a bottle of port or a samovar from its crate.

Fred, Jem and Dolores have had to buy winter clothing: heavy woollen coats, hats of rabbit fur, mittens and fleece-lined boots – quite an expense. We bears, of course, laugh at the Russian chill.

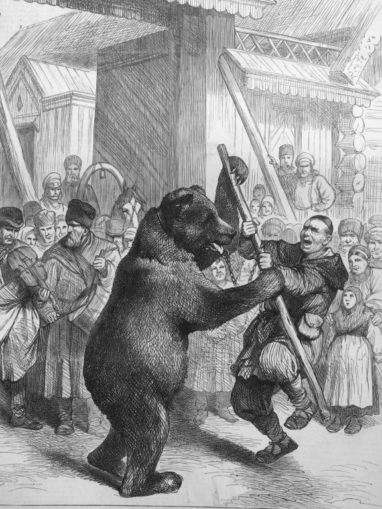

In the evening we repaired to an inn, thinking that we might perform and earn a little ready cash – we are by no means destitute, but a genteel sufficiency is always agreeable. However, when we arrived there was already a dancing bear, chained in the cruel old style while his keeper stamped around with a great wooden stave. The spectacle, so long forgotten, seared all our hearts, but there was little we could do. One cannot simply charge in and abduct a bear by force.

As I write this journal, I am interrupted. It is the Russian bear, trailing a length of chain which he has broken by main force. He has tracked us down to our cabin.

We are welcoming him as only bears can, and while we are feeding him with some of our bag of hares and grouse shot by Fred, Jem is cutting off his shackles with a hacksaw. His name is Boris. We are uncertain what to do, as we are not on the march as when we adopted Angelina, and his owner will be looking for him.

November 7th, 1809 (October 26th O.S.).

We decided that we must take the matter into our own hands before we were accused of abducting Boris. Accordingly, Fred and Jem went to the inn where Boris had been dancing, and soon found the bear’s owner. Fortunately he spoke a little French, as does Fred, and while their differing accents and vocabularies made communication slow they did not entirely impede it. He is called Alexey. They conducted him back to our cabin, where he found ten bears confronting him with a gaze that was not entirely friendly. Thus disadvantaged, he was obliged to bargain.

We began our negotiations with a dance. Jem played a stately sarabande on his flute, and my own dear Bruin and Angelina glided through its intricate evolutions with ineffable grace. He followed it with a lively gigue, and mercurial gaiety pervaded the cabin. Alexey watched open-mouthed.

Then Fred said to him simply – very simply in his halting French – ‘Alexey, you see what bears can do. We can teach your bear to dance like that. But no more chains, not never, no more sticks. Your bear is your colleague, your companion, your friend. Will you stay with us and we will teach him?’

Alexey, still dumbfounded by what he had seen, could say nothing but ‘Da.’

While Boris is being educated, Alexey will act as our guide to a new and unfamiliar land. He is not a bad man. He simply did not understand that bears are rational beings and do not belong to people. The spectacle of a band of bears living in freedom and harmony with three humans whom, had they wished to, they could have torn to pieces in an instant, has opened his eyes. They have been further opened by the realisation that, with a bear who dances beautifully, he can earn more roubles than he had ever dreamed of.

November 11th, 1809 (October 30th O.S.).

Alexey is teaching us the gopak, a dance traditionally performed by Ukrainian soldiers. It is a fine spectacle but strains the knees of humans and bears alike.

He plays a peculiar triangular guitar with three strings, which is called a balalaika. With Jem’s flute and Fred’s fiddle we have an orchestra of sorts, and what they lack in finesse they make up for in panache.

Dolores is now joining in some of our dances, to great effect.

Tutored by Alexey, the three humans are now able to speak a little Russian. Fred has found me a tattered Russian-Latin dictionary and a Russian grammar, and I am learning to write the language. The alphabet is easy enough, having been adapted from Greek by St Cyril and St Methodius in the ninth century by the addition of a few extra letters. The grammar is less easy: for example, nouns, in additional to the usual nominative, accusative, genitive and dative cases, have instrumental and prepositional cases, while some nouns add the vocative and locative (familiar enough from Latin), the partitive (a kind of alternative genitive) and the caritive (which negates the meaning of the word). But we bears make light of such complications.

November 15th, 1809 (November 3rd O.S.)

We considered our new performance well enough rehearsed, and went into the city to see how it would fare. The cold weather makes it harder to find a space to perform, for the patrons of inns are all crowded indoors and no one is in the yard. But, as we neared the centre of the city, we passed by the lighted windows of one of the fashionable establishments now known by the French name of café – though they are much finer than the coffee houses we knew in London. Its front gave on to a spacious square, swept clear of snow by serfs. Fred was struck by inspiration. ‘Let’s do the show right here,’ he said.

So our little band struck up a merry tune, and we bent all our energies to the dance. Dolores capered prettily in the centre, hatless, her red hair flying. By the time we started to perform the gopak, the windows were lined with elegantly dressed people, and they were beginning to trickle out of the door for a better view. We finished to rapturous applause and cheering, and several hats passed around the crowd gathered a harvest of roubles.

As Dolores was donning her coat and the men were putting away their instruments, a finely attired gentleman approached Fred and addressed him in French, asking who we were. Fred replied that we were an English company on tour (which sounded better than ‘fugitives from the law’) and that we had performed before His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales (which was perfectly true). The man said, ‘I believe that his Imperial Majesty Aleksandr, Tsar of All the Russias, would be graciously pleased to witness your performance. Would you be kind enough to give me your address?’

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file