9.

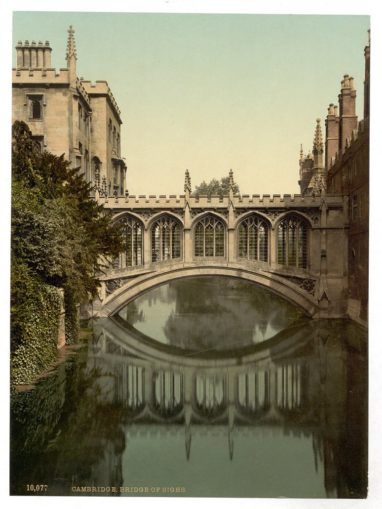

The continued ringing of the telephone brought us both abruptly out of the past and Cambridge.

‘Your Father!’ I exclaimed.

‘My Mother.’ She whispered.

‘Richard Conyngham here: we’re at Waterloo and due to arrive in a couple of hours’ time: e.t.a 11.25.’

‘That’s very kind of you. We’ll be the ancient couple, trying to look as if we haven’t a care in the world; I might even be trying to whistle insouciantly.’

‘ No, I don’t suppose many people do get off. Anyway, thank you so much.’

‘ What? Did she? But I’d rung off? Tell her love Loz too.’

Relaying this to Laura, I risked tears again, for her eyes brimmed, when I got to the bit about ‘Loz’.

‘I’d better try and make myself look respectable – if that’s possible.’ She said, looking down again, and went slowly upstairs.

After pacing fruitlessly about for some minutes, I sat in the chill of the study-end, telling myself I needed to sit near the phone. Then I remembered the car, and started up, headed feverishly for the near-ruin of a Stable which served as Garage and shed, coaxed the car into life, gingerly backed it out, turned it to face the road, and returned to my post by the phone. After a while, Laura looked in, as she had done before – not in a dressing-gown, but in what must have been one of her floaty Laura Ashley things, and looking as pale as Millais’ Ophelia. Neither of us could think of anything to say: I know my palms were already beginning to prickle with the sweat of apprehension. I could not begin to imagine what Laura was feeling like.

At quarter past eleven, I got up, found her stooping miserably over the range in the kitchen, touched her arm and murmured ‘Courage, mon enfant! We’ll be brave.’ and set off for the Station. On the way through the gateway, I came within a playing-card’s thickness of scraping the car’s rear wing on the gate-hinge (the rotten gates had been taken off over a year ago, stood against the garden wall, where they were still awaiting their fate: repair, or replace?). Finding it all too easy to drive either madly fast or funereally slow, I headed for the Station, pulled up eventually in the station-yard, parking as close to the entrance as possible, and went in.

‘Morning, Vicar. Off on a jaunt?’

‘No, Will: meeting some people on the London train.’

‘She’s late. Could be half an hour. Friends from London, then?’

‘A bit like that, Will.’

‘I thought from the look of you, maybe you were off to a Dentist or something. Anyway, friends, that’ll be nice.’

‘Yes…’ I let it tail off into silence, looked from my watch to the Station clock, and back again – and again: he eventually got the message that I wasn’t in a mood for talk, and wasn’t going to give anything away that he could retail to his wife at the end of his shift.

There was the sound of a train approaching and I began to nerve myself again, but it was only one of those immensely long trains of wagons full of gravel, that went on and on and on, rattling, clanking and squealing for what seemed like an eternity, finally clearing the station at just after half-past. By now, I was worrying about Laura, thinking of what she had said about the bath and looking at her wrists

A bell rang and in amongst a jumble of sound, I heard the announcer say ‘The Trwain now appwroaching platfwghorm hgrhrrrr , is the delayed eloghenthriipwhine-squeak from London WaterWHEE(whistle ring)…’. Even this seemed to take an eternity to arrive – and as long again to come to a complete halt. I heard a couple of doors open and slam, and braced myself as I walked forward on the platform. Apart from two railwaymen, there was only one couple. Lady Conyngham was taller and slenderer than I had thought, and infinitely more formidable; Sir Richard’s insouciance was, to my eye, skin deep: he has aged, I thought, since I last saw him, helping Laura pack up at the end of a term – and has probably aged most in the last twelve hours.

‘Ah, Padre, good to see you; good of you to act as a taxi service.’ He shook my hand. Lady Conyngham threw me a blistering look, half-profferred a gloved hand then withdrew it, inclining her head in acknowledgement in lieu, unfreezing her features for less than a second, and then sweeping out into the booking-hall and thence into the station-yard. She stared uncomplimentarily at my car, accepted my opening of the passenger front door, shutting it firmly herself and staring straight ahead. Sir Richard climbed in behind and in a fraught silence we headed back to the Vicarage, back to what ever lay ahead.

10.

Enveloped in the same silence, we got out of the car, and I led the way to the front door. We went into the hallway, which Lady Congyngham surveyed with evident distaste.

‘Shall we- go in here?’ I said, indicating the sitting room.

The sitting room was empty, apart from Bathsheba who looked insolently at us all before running unerringly towards Lady Conyngham and weaving in and out of her legs: I am sure the Ancient Greeks must have had a word for the uncanny ability of a cat to select the one person in the room who most hates cats – the ailurophobe – and make for him, or her. I thought she was in danger of being kicked away. Just as the atmosphere plunged to its most glacial, Laura entered. Sir Richard held out his hands towards her murmuring, ‘Oh, Lo, Lo!’ but before their hands could meet, Lady Conyngham sprang into action, freezing them both with a single gesture. With a still-gloved admonitory forefinger directed at Laura’s bump, and with a ferocious glare at me, she demanded, ‘And who, Laura, just who, is responsible for this?’. The ferocious glare turned to Laura, and then back accusingly at me.

‘Mummy, please, please!, don’t make things even worse. The man’s name was Roderick. We met once: once! I shall never, never, see him again. You might think that it’s his baby and that he should at least share in the shame and in the upbringing, but I will not marry him! I will not even let him know I have a child: she is to be mine, not his! Obviously, I meant nothing to him, nothing at all – less than nothing! He has played his part; a part both momentous, and insignificant. He has left the stage. I will bring her up myself! I will ensure that, at least until she marries, there will be another Conyngham.’ It was the Duchess voice again, and to my bewilderment, it was like a blow to the solar plexus on Lady Conyngham. In the face of such unexpected vehemence, such an adamant expression of will, she visibly wilted, and made for the door, scrabbling in her hand-bag. With Laura now holding her Father’s outstretched hands, I followed Lady Conyngham out into the hallway, indicated the study, and a chair, placing a large box of tissues I had had the forethought to put there close to her and stood there, although she was waving me away with increasing agitation. She looked up at me finally with tears now cascading down her cheeks, leaving sooty furrows of mascara fading down to the corners of her mouth, wiped her eyes, blew her nose, swallowed, choked a little and hissed: ‘You will not leave me?’

I would have sat knee to knee with her, but there was no other chair in reach, so instead I crouched, one hand on the arm of the chair she was in, both imprisoning her and steadying me.

‘Lady Conyngham, this is quite the saddest, saddest thing to have happened that I know of: it makes me sick, heart-sick, desolate: that this should happen to your lovely, innocent daughter. We cannot, cannot, rewind the tape, turn back the pages, reverse this event: we can, however, either make it better than it is, or worse than it is.’

‘How could it possibly be worse than it is? How can we possibly make it better?’ The voice quavered with competing emotions.

‘ Remember Samson’s riddle – “Out of the strong came forth sweetness, out of the eater came forth meat?” Some good can be brought out of this if we work together for it, if we can find the way; if not… As you’ve seen, as I think we’ve all just seen, Laura has unexpected depths of strength and determination; you could threaten – I don’t know – banishment, disinheritance, death, what you will – but you won’t, I think, get her to change her mind. All the single-mindedness with which she has pursued her academic career up till now will, I believe, be channelled into looking after her child. After all, it is a woman’s primal instinct, is it not, to protect and safeguard her child – at whatever cost. You love Laura, her father loves Laura, Sister Jessop only had to meet her for a second to love her: we all love Laura. If Laura is, as I am pretty sure she is, determined to keep this child we can, among us keep it a secret buried here in the depths of the countryside, if we wish: until we can work out a way of letting the story be told, in our way, in Laura’s way, as we determine. The birth can be registered here: place of residence – ‘The Vicarage’; father: ‘Unknown’. If it would help at all, I don’t mind being put in the firing-line: put me down as the father. We can control this event, rather than let it control us.’

As I paused for breath, Lady Conyngham straightened up and said in a cold, small, controlled voice:

‘Yes, I do love my daughter, that’s true: but since the day of her birth, if not before, that love has been masked by – had to fight with – my anger at the loss bringing her into the world caused me. I was a model, you know, when Richard and I met (quite a catch!) – all you needed then was to be tall and thin, personable, be able to stand in front of a camera, to take directions, and be a clothes-horse, although it did help to have some good connections. Laura took away my figure, not just in pregnancy, but forever! I already was very small’ – an elegant sweep of her right hand indicated where she was small – ‘and nursing her resulted in my losing even the very little I had; I regained my waist, but lost my – I would have been very successful in the androgynous 1920’s! Yet I could have gone back to modelling, and thus some independence, after a few months – the estate is not large, and runs, like most these days, pretty precariously. But after a year away from it, and in this reduced state, I was of no interest – a more buxom style, was to remain the vogue for years. And then, there was the conviction that Richard needed a son and heir, and I had failed him in the prime duty expected of a wife; of course, he never complained or alluded to it, but as soon as she began to grow up, I noticed how he taught Laura things that obviously he wished he had a son to teach: she rides, and hunts, and shoots very well, you know. For him, she became a substitute son, an honorary boy; soon I found I was resenting their closeness: so much from which I was excluded. Then when she began to develop, she had in abundance what I had lost. I’m afraid she’s seen precious little of my love over the years…’

The pause gave me my opportunity: daring to place a hand over hers, I looked into her mascara-streaked face and said, ‘Now there is a chance to show her that love: love is never wasted.’

Disengaging her hands far more gently than I had a right to expect, she stood up, as did I and, as we turned to make for the door, we saw standing motionless there, Sir Richard and Laura.

11.

How long they had been standing there, how much they had heard, we were not able to discover as a sudden draught, snaking in from the hall, followed by snatches of a conversation between Bathsheba and Sister Jessop, indicated the latter’s arrival.

‘All alone, as usual, eh?’

‘Mrrk.’

‘Couldn’t care less about you, could he?’

‘Mrrrr-row.’

‘Never mind: that’s men all over.’

‘Meuk.’

Bathsheba, insinuating herself between as many of Sir Richard’s and Laura’s legs as she could, came in, gave Lady Conyngham and me a look of huge disdain, turned and went out again, making sure her tail tickled as much of Laura’s legs as she could. Sister Jessop was made way for by Laura and Sir Richard.

‘Looks like a game of Statues! Laura’s mother? (how d’you do), father? (how d’you do): I’m Rosemary Jessop. Laura and I have already met. If the Vicar had had any sense at all, he would have ensured that you (to Lady Conyngham) and I had had a parlay beforehand – but that’s men for you! Right!’, as she plonked down her black bag. ‘Why don’t you (Lady Jessop again) and I, go into the kitchen and rustle up some sustenance, and bring it in to them all, in the drawing room?’

As bidden, we trooped our several ways, Sister Jessop taking a shopping bag with her, [as well as her black bag,] into the kitchen. None of us, I suspect, had ever seen Lady Conyngham so submissive.

‘We were not purposely eavesdropping’ (Laura)

‘Padre, we were beginning to wonder if my wife was all right…’ (Sir Richard)

After this simultaneous babble, quite a long silence ensued, then:

‘I certainly never felt I lacked an heir…’ (Sir Richard)

‘Why didn’t she ever tell anyone all this?’ (Laura)

‘Lo? Do you reckon it’s a good idea if we speak one at a time?’

‘Yes, Daddy.’

‘First go’s?’

‘Yes Daddy!’- with Laura’s inimitable chuckle.

‘ I had a tough job last night, believe me, after you’d so kindly rung, Padre: Ysobel- ’ (he gripped Laura here, by way of translation) ‘was, as any mother would be, very upset about the news, and I apologise if she was a trifle brusque, indeed offhand, at the Station – and, again, here. I have to say, what I heard moved me almost to tears – what each of you said: so sad, so sad. Such misunderstanding. But Lo – my little Laura here – is a staunch young thing, and among us all, I’m sure we can work out what’s for the best.’

He turned to her, having held her tightly all the while, kissed the top of her head, and then abruptly sat down, mopped his face with an enormous silk handkerchief, and blew his nose – twice.

Laura took her father’s hand, entwining their fingers and then, with her other hand patting his, looking straight at me, began a little speech – like the Vote of Thanks Given by The Head Girl: ‘It’s immensely good of you, you know, to put up with all this – strangers invading your house, disruption, tears, tantrums, ill-humour, a sorry state of affairs – and the kindnesses you have shown me, the kind things you have found to say about me, to say nothing of the generous hospitality, are all deeply appreciated. And – and I would like the little soul to be called Rosemary…’

Just as her already misty eyes began to glitter, and her voice to quaver, Sister Jessop and a no-longer mascara-furrowed Lady Conyngham came in with two trays. We stood and sat around, browzing at bits of cheese, at ham, at pate on biscuits, at gherkins, at olives; we sipped at some cheap but deliciously cold white wine; we talked, almost as at a cocktail party; I hugged and kissed, or was hugged and kissed by, everyone except Sir Richard – who took my hand, shook my hand, and held my hand.

At length, Sir Richard and Lady Conyngham thought about trains; I found that the next – if not the only – one to Waterloo was in twenty minutes. I was going to drive them, but Sister Jessop reckoned I’d had far too much wine and said she’d drive them, which, despite all the anonymity-thing, they accepted. Sir Richard hugged and kissed Laura, murmuring encouraging things in her ear; Lady Conyngham tightly embraced Laura, clasping her head to her bony front, while they both silently shed a tear or two. Then, in the almost tuneful sound of a Morris Minor’s exhaust, they were all gone.

Laura was already tidying up the plates and glasses when I came back from the door: we each carried a tray into the kitchen. To my surprise, she needed no dissuasion to stop her doing the washing up. Instead, she flopped into her chair, feeding on small pieces from the plates. Then, with a sigh, she said, ‘Do you know what I’d love most of all?’

‘No.’

‘I’d love a longish wallow in a scented, foaming bath!’

‘Then Blenkinsop will run one, for her Ladyship!’ I said.

Fortunately there was still plenty of hot water: I turned the hot tap on full, swished the water round, put towels to warm on the pipes, ransacked cupboards all over the place but all I could find was a wrapped bar of Pear’s Soap, and another of Wright’s Coal Tar: I took the Pear’s. Going into my bedroom, I grasped the rather expensive bottle of ‘Eau de Toilette’ I’d got last Christmass, took it into the Bathroom, unscrewed the top, and poured almost half its contents into the bath; the smell was overpowering. I checked the temperature of the bath – and again, with my elbow. Going back downstairs, I assumed the air of a servant and coughed before entering the kitchen, where I said:

‘Her Ladyship’s bath is now ready, so, if her Ladyship would care to…’

Entering into the spirit of the charade, Laura stood up and, with an icy glance at me said: ‘Thank you Blenkinsop: I will call if I need you.’ She swept, but slightly wobblingly, up the stairs. I couldn’t resist following her, mimicking Richard Briers with ‘If you’re sure that’s all, your Ladyship … ?’ She went, of course, into her bedroom, so I sat on the stairs for some minutes, until she swept out (again, in the old dressing-gown) to the bathroom. Once in she called, ‘Blenkinsop?’

With a tea-towel over my fore-arm, I limped in and asked, ‘Yes, Your Ladyship?’

Her Ladyship was still in the old dressing-gown.

‘Blenkinsop, if I need my back scrubbed, I will call for you.’

‘Thank you, your Ladyship; I will bear that in mind. I trust the temperature of the water is to your Ladyship’s liking?’

‘Thank you, Blenkinsop, it is.’

‘And the soap meets with your Ladyship’s approval?’

‘Indeed, yes.’

‘The scent…?’

‘Yes, Blenkinsop, very good, Blenkinsop. Thank you Blenkinsop: that will be all.’

‘The towels are, as your Ladyship has no doubt seen, warming…’

‘You will not leave me?’

I then knew approximately how long she and her father had stood in that doorway below.

12.

I was not entirely expecting her to come downstairs again, but, if she did, I expected her to look refreshed and soothed, not anxious and frightened.

‘I feel so strange.’ She said.

I got her to sit down and indicated the kettle, but she merely shook her head.

‘It’s probably nothing.’ She said, and then winced and made a little gasp.

‘Phooh!’ she exhaled, her eyes now wide and alarmed. I was frozen. A few more moments passed, and I could see that she was pursing her lips, then biting her lower lip.

‘The bath!’ I said, self-accusingly. She shook her head. Then another one hit her, and she almost doubled up. I was running now, tripping over Bathsheba in the gloom of the doorway, who gave a pained yowl, heading frantically for the phone.

After what seemed an eternity, Sister Jessop picked up the phone.

‘Stop jabbering, man: calm down or you’ll frighten her – you’re frightening me!’

‘Yes, I know, you’ve told me as much. Get her to come and sit by the phone – don’t put it down you idiot! Tell her she’s going to speak to me and make sure – oh it doesn’t matter, I’ve got my watch here. Quick about it. Come on!’

Racing back into the kitchen, I found Laura sitting there looking exhausted and terrified, with Bathsheba on her lap, purring like a small Morris Minor. I put the cat on the floor, took Laura by the hand, and led her into the study, telling her with exaggerated slowness, that Sister Jessop was on the phone. Laura held the phone with both hands to try and mask the trembling and her voice was small and almost helenium-high.

‘I’m not sure – I think so, but I was in the bath when the first one came… so I don’t really know… Here comes another one. Mmmphhh… oohh. Whooh! Hoo, hooh,… hoohh.’ She had dropped the phone into her lap, picking it up again with wildly shaking hands.

‘Yes, I see; thank you; yes, I’ll get him to do that… hang up now? Right. Please don’t be long: I’m so frightened!’

I took the phone from her hands which were wet with sweat, put it back on its cradle, grasped her outstretched left hand (her right was rubbing the bump), helping her to her feet.

‘She says… mhmmn … to get me upstairs…mhmmmn – phoh, lie me on the bed… phooh…ho-ooh… put a large kettle full on the simmering… get a bowl…she’ll be there.’ I could see great beads of perspiration on her forehead as we went up the stairs,lowly, tread by tread; I patted some of them away with my handkerchief. We had to stop part-way as another one hit her, this time arching her back and nearly sending the two of us plummeting back down.

‘Don’t leave me, please don’t leave me!’ she wailed, as I shot off to deal with the kettle. Even Bathsheba managed to look concerned, almost anxious: as I rocketed into the kitchen, she trotted off in the direction of the stairs…

Dashing upstairs again, I saw that she was lying on the bed, looking not just exhausted but wild-eyed: I found myself asking ‘Is she going to die?’. I held her hand, and said: ‘Please don’t!’

‘What?’, she gasped.

From who knows where, some inspiration came to me: ‘Laura, it’s going to be all right: I absolutely know it is going to be all right. Yes, I’m a pretty useless sort of person to have here, not at all what you really want or need, and I don’t understand more than about a tenth – if that! – of what’s going on round me, but every atom of me is willing you to get through this – every fibre: I – I couldn’t bear you not to! If I can somehow take away any of this pain, I will: transfer it to me – I can’t bear to see you suffering like this. I promise I won’t leave you, I’ll stay here, I’ll stay here…

‘Go! Men are banished!’ Sister Jessop had arrived some time during this interchange.

‘But, I’ve just said …?’

‘Sorry, Vicar: this is definitely girls only – until we call you. JUST GO AWAY!’

I hadn’t even Bathsheba’s dubious company in the kitchen: she had insinuated herself into the bedroom, and, when I was being ejected by Sister Jessop, I had seen her sitting on the dressing-table, avid and yet complacent.

After a time in the kitchen, finding the regular cries from above more upsetting than I could account for, I went down into the cellar, where Laura’s yells were less heart-breaking. I went, torch in hand (the cellar had no light), into all its recesses. The smell was mushroomy and, in a way refreshing – certainly cool. Spiders, long inured to darkness – what did they live on from year to year? – jigged in their webs, or remained still, the torch’s beam showing them to be mere shed skins, or spider-skeletons. As one particularly heart-rending cry echoed even down here, I went far further than I had ever gone before, and made two discoveries. The first was of a wine rack; the second was of several dozen bottles of wine, so shrouded and caked in dust that it was impossible to see what they were, though a half-bottle was in my hand when an imperious bellow got to me:

‘Wherever’s the wretched man gone? I told him to go away, not to emigrate!’

Rushing up the cellar steps, I surfaced in the kitchen. ‘Sorry.’ I said ‘Kettle.’

‘Good God, man, we had that years ago. Whatever’s that you’ve got in your hand?’

‘I don’t quite know,’ I said – ‘I was bringing it up into the light.’

‘Trust you!’ she snorted. ‘Much more interested in the past than the present!’

Sister Jessop sank into Laura’s chair. Somehow, she managed to look not just exhausted, but radiant.

‘I think this definitely calls for a drink, Vicar.’

‘What…?’‘… I said to her, Laura, the head’s out now (I knew then!): just one more push, sweetie… and she muttered ‘Rosemary, Rosemary’. I said I’m here, you clever little darling. She said, ‘I want her to be called …’ Then there was one more contraction and out it slithered. I took up the little thing, placed it on her tummy – vernix, meconium, cord and all – and said, You can’t call him that, my dear, it’s a boy: a fine, healthy, perfect boy!’

Rather like Laura’s father, I planted a kiss on the top of Sister Jessop’s head.

‘You sentimental old thing!’ she expostulated, but there were joyful tears in her eyes.

Looking at the bottle in my hand, I saw from the wire that it was Champagne of some sort. ‘I’ll open it!’ I said.

‘Take it up, with a couple of glasses to the Dear Child –tell her we’ld still be able to prescribe it – and Brandy, and Guinness – but for Harold Wilson. Just let me alone with that Port of yours,’ she said. ‘- if there’s any of it left.’

There was some left: I put the bottle on the kitchen table, together with a glass: Sister Jessop was still beaming reflectively, nothing needed to be said. With the half-bottle and two glasses on a tray, I set off upstairs.

Strangely, I didn’t feel the need to knock: I just pushed open the door and went in. I had planned to say something like, ‘Her Ladyship has requested some refreshment, after her exertions?’, in a Blenkinsop way, but all I did, not so much say as yammer, was, ‘I was so, so afraid – afraid that, that you were going to…You look phenomenal, wonderful – absolutely radiant, lovely, marvellous. So brave! So clever! Congratulations. They’ll be so proud. Just look at him! Who’d have thought…! You really are the most amazing…! By the way, I think I’m going to cry.’

She just smiled me that smile, so when I found my voice, I said, ‘I came across this in the cellar and it’s possibly quite disgusting, but Sister Jessop has instructed me to bring it up to you…’

Her eyes came quickly into focus, she touched the bottle, looking closely at the label, and said, ‘It looks very like some Daddy has, but he says there’s not much of it left now, so it only comes out on very special occasions.’

‘Well, this is the most very special occasion…very, very, special’

‘We last had a glass each for a special Royal Birthday.’

‘This is a special Birthday, and you Conynghams are almost royal,’ – she looked quite severe at this – ‘and if he can’t be called Rosemary’ (she chuckled, contentedly) and isn’t a Prince (Prince Rosemary!) – well, you all professed to think you knew how Republican I was – Guardian-reader, you reckoned, and all that: Ha! – we can drink to: – Citizen Conyngham, and Citizen Conyngham.’

I hadn’t been able to see the label under the grime, but, looking at it now, I saw that it was a Louis Roederer. I opened it and it made barely a phpp, poured some out into the two glasses, where it looked golden and held two or three constant, slow threads of tiny bubbles. I was relieved to see that there was no tremor in her hand as we clinked glasses. She looked down, and with that so characteristic chuckle said ‘To Rosemary!’ ‘To Laura!’ I said. The wine was sweet, heady, and honeyed in its warmth and beneficence. We drank it all; I think I even, for just a few moments, joined ‘Rosemary’ in reclining on the Mother’s breast.

© Jethro 2022