May 20th, 1809.

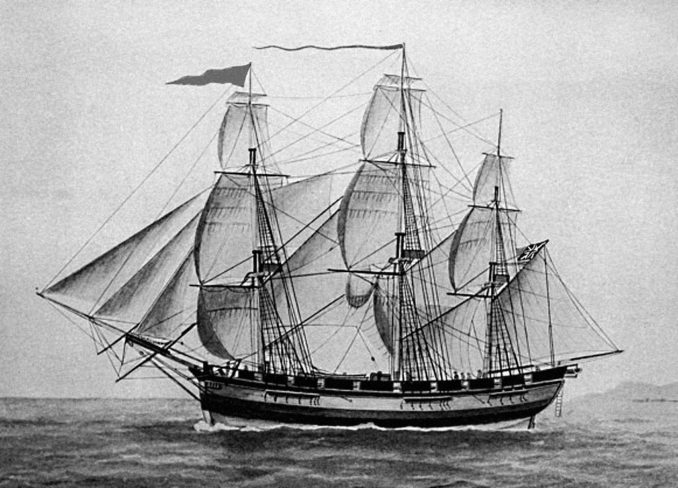

We are at sea again – on a merchant ship, Pride of Scunthorpe, under the command of Jonas Swigger, a jovial captain who was more than happy to take us bears and Fred and Jem as able seamen – or sea bears. We are an asset to any ship.

The voyage has not been without incident. Yesterday we sighted a brig upwind of us, flying the Red Ensign. It closed on us, and we were about to exchange friendly communications when all of a sudden the flag was hauled down and the hideous French tricolour hoisted in its stead. It was a French privateer, and we had been the victim of a ruse de guerre or, as they say in England, a dirty trick, for which we were quite unprepared. Our vessel has a few cannon, as any merchantman must in these troubled times, but they were not run out, and in any case I doubt whether the human sailors would have been able to man them.

The privateer fired a shot across our bows, and open gun ports revealed a row of muzzles pointing ominously at us. We hove to, as we must. But Captain Swigger was not one to yield without a struggle. He conferred briefly with Jem and Fred, who directed us to creep across the deck, shielded from view by the gunwale. As the French closed on us, with the boarding party ready to leap across, nine bears wielding cavalry sabres suddenly reared terrifyingly into view, stopping them in their tracks. A few wild shots from sharpshooters in the rigging of the tossing French vessel failed to strike us, and with one bound we were on the privateer, rapidly reducing the would-be boarders to their component parts.

English sailors followed us with cutlasses and pistols, and between us we dealt with the gun crews. The rest of the French surrendered and threw down their weapons.

The privateer’s captain was among the survivors. Trembling, he answered our questions. The brig is called Incroyable, and his name is Jean-Marie Couillon, with a licence from the Corsican tyrant to harry shipping and purloin cargoes. It seems that his exploits are all too well known. We threw him into the forecastle with the others and searched the hold.

There was a fair quantity of brandy and tobacco, no doubt stolen from honest traders. We took this on board without delay. Captain Swigger conferred with Jem and Fred who, now the leaders of a successful boarding party, could no longer be considered mere crewmen. They agreed that we had just enough men and bears to take Incroyable as a prize and sail her to England. We bears are to be the prize crew, and the men are to do what they can to keep Pride of Scunthorpe pointed in roughly the right direction.

May 25th, 1809.

Incroyable is a well built vessel, dry and weatherly, and a delight to sail; but the French have left her in a most slovenly condition. If we are to get a good price for her, she must be shown at her best. We have been scrubbing the woodwork, polishing the brass, and holystoning the deck to remove the bloodstains. We found a small amount of paint in the locker, enough to patch the more weathered parts of the sides.

May 30th, 1809.

We sailed in convoy across the stormy Bay of Biscay, around Ushant, and past the Lizard and Start Point. We cannot let the French sailors out of the forecastle, where they have been subsisting on a scant diet of weevilly ship’s biscuit and green water, and have had to man – or rather bear – the vessel unassisted. But she is speedy and tractable often we have had to shorten sail to allow Pride to catch up with us.

Our frequent delays in keeping pace with the slower ship have given us much practice in handling the sails. With only nine aboard a two-masted brig we would usually be considered undermanned, but we are bears and can haul many times more strongly than a mere human, and are now working with an alacrity that would be the envy of His Majesty’s Navy. It is then the task of little Henry, smaller than the other bears, to stand at the wheel, and I have been training him in this necessary skill. Despite his tender years he is a bear of good sense, and we all trust him completely.

How can I express the delight of being in command of a ship, the wind singing in the rigging as she responds to the turn of the wheel while eager bears stand ready to trim the sails? It is the joy of the dance, but in a different theatre. This time is, in the words of Homer, δόσις δ’ ὀλίγη τε, φίλη τε, a rare gift and a precious one.

Fred came across in a boat to tell us what he and the captain had planned. Of course, it is for a merchant ship to capture a privateer, but they are confident that the usual rules will apply: the Admiralty will agree to buy her from us, and the prize money will be shared out among our crew.

Not for her full value, I wrote on Fred’s slate.

‘O’ course not,’ said Fred. ‘But it’s a dirty business and yer does what yer can. One thing, though – we ain’t givin’ ’em that brandy and baccy, no way we is. The captain knows some folk who’ll give us a good price for it. So we’ll be stoppin’ shortly to land ’em.’

So now we add smuggling to our repertoire. As Ovid said, Video meliora proboque; / Deteriora sequor – ‘I see better things and approve; I follow the worse.’

June 5th, 1809.

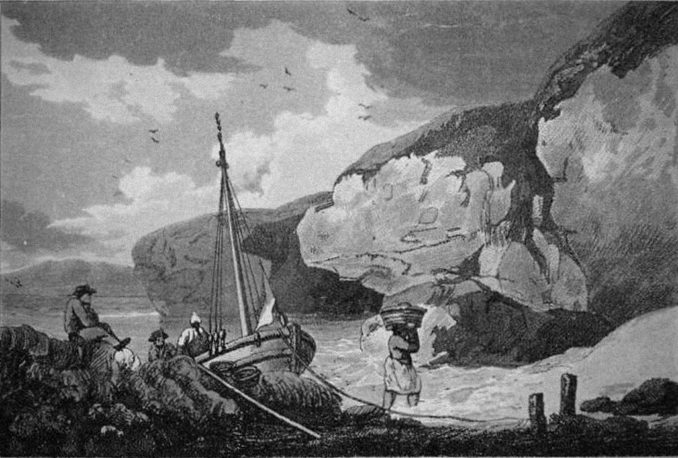

Under cover of night we anchored off a small cove on the Dorset coast in which lies the tiny fishing village of Eype, accessible only by one small lane, an ideal spot for clandestine activity. June 4th is the King’s birthday – poor mad old monarch! – and we hoped that the excisemen would be celebrating it properly in a Bridport inn.

Captain Swigger, Fred and Jem went ashore in a boat to make the necessary arrangements, and returned in two hours to say that all was well. Bruin, myself and two other bears went across to Pride to help with the barrels. We will also be useful in the landing party in case any of the folk on shore decide to renege on their bargain.

We waited for the signal, five flashes from a covered lantern on the cliff, and rowed ashore with muffled oars, to meet a furtive party who had at least had the good sense to bring a mule and a wooden sledge to haul our cargo up the stony beach. There was a chink of money being counted. They had kept their word – which, Captain Swigger remarked, ‘is more than we can expect from the bloody Admiralty’.

Away before dawn, bound for Portsmouth.

June 7th, 1809.

We approached Portsmouth knowing that the outline of the notorious Incroyable would be all too well known to those on shore, but we hoped that our steadfast display of the Red Ensign would at least secure a delay in which we could explain ourselves – though it was the same flag that had been used to trick us, newly washed and patched with pieces from the red part of the damned tricolour as well as we could, for sewing does not come easily to a bear. The presence of the familiar Pride of Scunthorpe following close behind would be reassuring.

We eased in under topsails only. Four bears to each mast to haul the larboard and starboard clewlines and buntlines, and the sails were up in a trice. Almost before the anchor had struck bottom we had raced up the shrouds and were furling the sails trimly on the yards. It was an arrival to be proud of, and we were sure that it was noticed.

Pride arrived more slowly and less elegantly, and the crew bundled up the sails somehow, in the manner of merchantmen. We were not surprised to see a cutter heading out promptly to meet us.

However, the men aboard the cutter were very surprised indeed when, in response to their hail, nine bears’ heads appeared over the gunwale. I think they might have fired on us, had not Fred’s reassuring voice sounded through a megaphone from the deck of Pride: ‘All’s well, sir! That brig there’s a prize, an’ them’s English bears, an’ fine sailors too. Pray come aboard ’ere an’ we’ll ’splain it all to yer.’

I though it best to attend the discussion so, when the men had climbed the rope ladder to the deck, I dived into the sea, swam rapidly across, and went up the ladder, arriving dripping on deck to their consternation. ‘’Ere’s Daisy,’ said Fred, ‘captain o’ the prize. Daisy, meet ’is Majesty’s Lieutenant Snipe.’ I held out a paw and, to his credit, the officer shook it.

‘So these are the famous bears,’ said Snipe. ‘We have heard wild rumours of their doings in Spain. Is it true that they routed the French cavalry?’

‘Indeed it is, sir,’ replied Fred. ‘An’ twice too, at Sahagún and Grijó. An’ now they gone and taken that there brig. We wouldn’t be where we is now wivout ’em, in fack we’d be guests o’ Boney.’

Jem added, ‘An’ we got the crew – them as is left of ’em – shut up in the fo’c’sle of Ink Royble. She ain’t damaged a bit, neither. Would yer like to see ’er, sir?’

We went down the side and rowed over to the brig. The bears lined up as we climbed aboard and gave the Lieutenant a smart salute. He looked approvingly at the clean deck, the neatly coiled ropes and shining brasswork. ‘A trim little vessel,’ he said. ‘I reckon she could fetch fifteen hundred at the prize court.’

A few yells of French execration sounded from the forecastle as we passed. ‘There’s sixteen in there,’ said Fred, ‘includin’ that Cap’n Cullion. The rest was dinner for the sharks after we’d finished wiv ’em.’

‘Sadly, I don’t think you’ll be getting head money for privateersmen,’ said Snipe. (He was referring to the traditional payment of £5 for each enemy sailor captured.) ‘In fact we’ve heard some nasty tales about Couillon, and more than likely he’ll be facing trial for piracy and an appointment with the hangman.’

The Lieutenant returned to his cutter, promising to return shortly with Marines to take off the prisoners. ‘Did you ’ear that?’ said Jem. ‘Fifteen ’undred quid! Even after it’s shared out wiv the Pride we’ll be rollin’. An’ that’s on top of what we got for the brandy an’ baccy.’

We had netted £500 for our smuggled cargo, shared out with a quarter for the captain and the rest divided among us – twenty-two men and eight bears getting £12 10s each. If Incroyable raised the promised sum, each of us would benefit by a further £37 10s. Though we bears are not much moved by the prospect of wealth, we capered around the quarterdeck as Jem played a merry jig on his flute.

Two hours later the cutter returned and the prisoners were herded into it by stony-faced Marines. ‘Reckon you’d best come ashore with us, and bring all the bears,’ said Snipe. ‘We’ll put your boats in tow for you to get back. Word’s out in the town, and folk would like to see you. I think you’ll be pleased with your welcome.’

And so we were. The honest citizens (and, I have no doubt, the dishonest as well) lined the quay as we arrived. We were garlanded with flowers and led in a triumphant procession through streets lined with cheering crowds. I have never been so proud of my gallant band of bears.

We halted in front of the Guildhall, where an impromptu celebration was held. But first, Fred had to make a speech from the steps. Blushing with embarrassment, he delivered a halting and modest account of our adventures in the peninsula, interrupted by frequent cheers.

We were plied with ale, and there was music from a Marine band – but, as Xenophon put it, ἥδιστον ἄκουσμα ἔπαινος – the sweetest sound is praise. We danced with the townsfolk till long after midnight, then reeled back to the quay, carrying little Henry who had been overcome and was snoring. We rowed in a splashy and disorganised manner back to our ships, and collapsed on the deck under the warm summer stars.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player