Just off Red Square in Moscow, by a Metro entrance, is a curious little basement exhibit, the Museum of the USSR. The day I visited it, I was almost alone as I viewed the dozen or so rooms, which sought to recreate a typical Soviet home (which would actually have had about three rooms, but there were a lot of dial-up phones, Beatles records and record-players, black-and-white TVs, projectors, schoolbooks, toys and nested dolls to stuff in there). It all looked cosy but cramped. Who, I asked the lady on the reception desk, really harkens back to the USSR? “Those who lived there,” she replied.

I suppose she would say that. But it is a fact that many older Russians do hanker for those days, including some of the power-holders. This is clear from the evident reluctance of the state to remove the old names, icons and symbols of the Soviet regime. In one of the audio language courses I used before this trip, the narrator states, “if you ever get lost in a Russian town and want to know where the centre is, just ask for Lenin Square. Because every big town will have one.” Indeed, St Petersburg did have one, but for greater accuracy I’d tweak that claim to Lenin Square or “Prospekt” (Avenue).

It goes beyond that, though. Approaching St. Petersburg, for example, you drive under a big sign that says “Hero City Leningrad,” and the same slogan stands high opposite Moskovosky Station. Many public buildings retain their old carved hammer-and-sickle motifs, and you even see the odd hammer-and-sickle flag flying. Plaques in towns across west Russia remind you of the war and the glorious victory of the USSR. All this stands in stark contrast to Eastern Europe, where all the symbols of the old regime have been scrupulously removed from public life. In Russia, though, those old insignia look down from pediments and under eaves, like owls watching and biding their time. In Eastern Europe, the Communist period is viewed as an aberration, a disastrous deviation from the natural path of European history. In Russia, it is seen more as an integral part of the long continuum of national development, contributing its bit to Russia’s rise. After all, this brutal and failed utopian experiment did briefly make Russia the de facto No. 2 power on earth.

A revealing question to ask Russians of all ages is, which of the leaders since 1917 is the most fondly remembered? I confess I was surprised by the most frequent answer. No, it was not Stalin, and nor was it Gorbachev. The name that came up was usually Leonid Brezhnev. In the West, and in my assumptions as well, Brezhnev is associated with stagnation, repression and the irreversible decline of a Soviet model turned sclerotic after the heady years following the Sputnik. That, though, is evidently only half the story. In Russia, the word they use for this period is zastoy, literally meaning stagnation but with nostalgic connotations.

So what exactly did people actually hanker after? I asked the museum steward. “Stabilnost’,” she replied: the same answer I got from three others I asked. Stability. “Even though life was very skromnyy, we had enough (I again drop a Russian word, as it encapsulates these times: modest, frugal, humble). And human relations were better.” And what about the downsides? “Lack of things in the shops and of freedom to travel.” Again, what everyone said. Curiously, nobody I asked mentioned political freedom, though expat Russians I’ve met certainly did care about this.

What of the other Soviet leaders? Two names strikingly absent from street names today are Stalin, who was “cancelled” long ago, and that of the man who cancelled him, Khruschev, who is regarded as a jumped-up “kolkhoz administrator,” incompetent and disrespected in the words of a teacher I talked to at length, Sergei. Yeltsin and Gorbachev, he went on, are universally despised, if not hated outright. Why? In a nutshell, many Russians did not regard the end of the Soviet Union as a liberation, but as “the theft of our country.”

What Sergei meant here was that many had believed the Soviet Union could have reformed itself from within in the way of the CCP in China, which since the 1990s has presided over the greatest rise in living standards in human history. This possibility is what Gorby stole. I don’t necessarily accept this view. I don’t know; I’m just reporting. What I do know is that many Russians hated the tyranny of the USSR, and must have felt privately grateful to Gorbachev. But it seems they aren’t the majority and do not dare to show it. There aren’t many Gorbachev or Yeltsin Avenues in Russia.

If Lenin remains the standard-bearer of the revolution in street iconography, what of Stalin? Though Uncle Joe’s name vanished from street signs, you do bump into him, in sometimes bizarre places, like souvenir shops with avuncular little plastic busts and portraits of him on display. (Imagine going into a Berlin souvenir shop and finding a grinning plastic bust of Hitler).

But what do people really think of the old tyrant? A significant minority certainly do sincerely admire Stalin. But not hotel receptionist Ingrid, who was old enough to remember those times: “I hate him. He killed so many people. And for many of his admirers, it is just for show.” Others accept that he was a monster, but argue that the modernisation of the Soviet Union could not have happened without him. “Before him, this was an agricultural state,” Sergei said, “and after him an industrial state.” And they argue, with reason I think, that the USSR could not have defeated Hitler without that industrialisation, or without his ruthless leadership. Obviously, there is much more to say on this, but that would be a separate essay.

So how serious is the nostalgia for the Soviet Union? Much of it is bound up with happy childhood memories, as is indeed the hankering of our own oldies (like me) for the 1950s and 1960s. Nobody really wants a return to the queues, the power cuts, the privations, the censorship, the oppression, the travel ban, the lack of choice or opportunity, the corruption and the overall dysfunctional lunacy of the Soviet system. Today’s Russia is so far removed from that world that any attempt to go back to those days would be stoutly resisted by anybody under 50. Not even Putin wants that. And nobody in Russia wants to again go through the nightmare of being an occupier of hostile countries (which is why the invasion of Ukraine will stop at the Russian-majority areas).

And yet elements of the Soviet Union do live on in today’s Russia. Much more important than the knackered old Ladas and hammer-and-sickle flags are the invisible things. One example: Because flats are so expensive now, many Russians today live in properties inherited from their grandparents, many of whom were effectively gifted their state-owned flats after the fall of Communism.

Sergei pointed out some other less welcome similarities. “We are just as corrupt as they were. Take a public works contract worth $100,000. The actual cost will be $10,000, but the winner of the tender will pocket the $90,000 excess himself and from that hand out big sums to friends and family. That sort of corruption is so endemic here that when the government plans something, people routinely ask, “Yest’ interes?” — Is there an interest?” or in plainer Yorkshire, “is there owt in it for me?”

There’s more. “Some people think we have now entered a new period of zastoy.” Another period of complacent stagnation. How many Russian manufacturing brands could I name? I could only come up with three, and two were not strictly manufacturers: Gazprom, Rosneft and Lada.

“Now think of South Korea. One third the population, a fraction of resources, and yet they have produced Samsung, Hyundai, Daewoo, LG .. They make stuff. We don’t. Russia has nothing to compare. Even our arms industry, all those new weapons are just upgrades of Soviet-era designs. Under Yeltsin and Putin, the government has been happy to just sell oil and gas and do nothing much else. No real investment in manufacturing. There is a feeling here that for all the nationalist posturing, the government doesn’t actually care about the country or the people.”

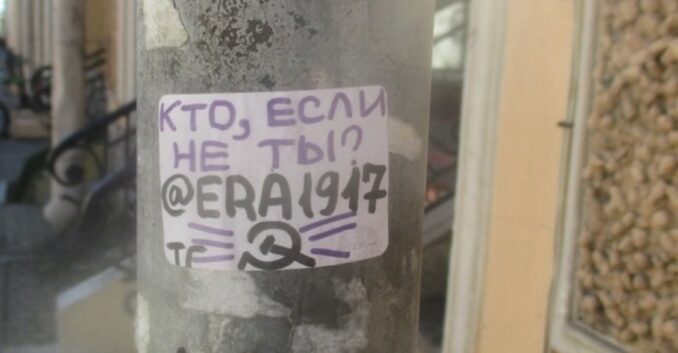

One paradoxical — if not downright bizarre — consequence of this, he said, has been a minor revival of Communism. Not the legacy movement of Gennady Zyuganov, which is more concerned today with protecting SMEs than fomenting revolution, but a youth movement that seeks to draw on the “spirit of 1917” to shake Russia out of its perceived torpor.

The majority, though, have no part in this and keep their heads down. And though I am an outsider with only superficial knowledge, I did not entirely agree with Sergei’s diagnosis of Russia’s failings.

The comparison with South Korea is telling in another way. In 2000, South Korean income per capita (by World Bank stats) was $18,410, while Russia’s was $6,650. In 2020, South Korea’s was $35,490, and Russia’s $15,320. It is Russia that has more doubled its GNI in this period, not South Korea, yet it is Korea that is regarded as the economic miracle, while Russia is the “gas station with nuclear weapons.” I would add that, having stayed or travelled both in these countries over the last 30 years, I do not believe South Korea is or ever was twice as wealthy as Russia. They have always had roughly the same standard of living. Both grew together. But that’s stats for you. In fact, the transformation of Soviet Russia into today’s Russia is more akin to China’s rise, even if it is all down to energy exports. But nobody wants to acknowledge that. Nor is it true, IMHO, that today’s Russia lacks dynamism — a number of huge projects are now underway, from the Arctic shipping route and civil aviation to cross-border rail and pipeline projects in the south.

In conclusion

Today, whatever ails the Russian polity, the country itself is a clean, safe, modern place with good infrastructure, full shops and a sophisticated, friendly people. Russians are not regimented: they have similarly varied habits and tastes as elsewhere in Europe. What you don’t find, and I frankly don’t miss, is the stripey flags, and the climate emergency and diversity claptrap. Overall, I thought Russia was only a little behind the Baltic states and Poland in de facto living standards and on a par with Romania — progress achieved without the very considerable help of the European Union.

“How will the Ukraine war end?” I asked Sergei.

“Nobody knows. And everybody is fearful.”

I will close this essay with my own prediction. If you want to know how the Ukraine war will end, look at a Russian TV weather map. You will notice that Donetsk and Lugansk are already treated as integral parts of Russia, like Kaliningrad or Sochi. Kharkov, Zaporozhia and Kherson are not, despite their supposed incorporation into Russia by legal instrument. I think they never will be. The current front line will be, more or less, the new frontier.

Looking beyond the Ukraine disaster, Russia has a bright future, especially now that its partnership with China is deepening. Theirs is a very complementary relationship: Russia supplies the energy and advanced tech in certain sectors, while China provides the manufactured goods. This creates a self-sufficient regional economy beyond the reach of US interference and immune to sanctions. All Russia has to do is incentivise its couples to produce children.

“Sergei” here is two different people whose quotes I have used.

© text & images Joe Slater 2025