Drawing the line

From 1895 until the Third Afghan War of 1919, Afghanistan experienced a period of relative political stability marked by attempts to consolidate internal control, manage external pressures, and maintain independence amid the broader context of the Great Game — the geopolitical rivalry between the British Empire and Tsarist Russia.

In 1895, the Durand Line Agreement was finalised between British India and Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, Afghanistan’s ruler from 1880 to 1901. This agreement demarcated the border of British India and Afghanistan, defining what would become a contentious boundary, more so in the Pashtun areas.

Though the line clarified spheres of influence, it split ethnic Pashtun and Baluch populations in the two territories, sowing long-term tensions. Abdur Rahman Khan accepted the Durand Line in part because it permitted him to retain power and autonomy within the borders of his country, albeit at the cost of relinquishing claims to tribal regions.

Back to England

This denouement allowed my ancestor, a great-grandfather on my father’s mother’s side, to return to England pinned with an India Service Medal with Waziristan 1890–95 clasp. He left our local regiment, the Border Regiment, and married well, to the daughter of a respectable Buttermere farmer. He fathered a trio of daughters of his own, the youngest of whom was to be my father’s mother.

In old photographs, he presents as every inch the well-turned-out, rather grand late Victorian gentleman. Employed as a messenger in the municipal gasworks, he died in his sleep in his seventieth year. ‘Three score years and ten shalt thou labour on the face of this earth.’ Rest easy, soldier, your watch is over.

© Always Worth Saying 2025, Going Postal

Back in the Stans, Abdur Rahman ruled as a strong, centralised monarch, using authoritarian methods to unify the country and suppress tribal dissent. His regime focused on modernising the military, introducing a more structured bureaucracy, and reinforcing central control over the provinces. He remained suspicious of foreign influence and maintained a policy of controlled isolation, wary of both British and Russian intentions.

Reform and Resistance: Habibullah to Amanullah

After Abdur Rahman’s death in 1901, his son Habibullah Khan succeeded him. Habibullah continued many of his father’s policies but was less autocratic and more inclined toward modernisation and reform. He introduced limited judicial and educational reforms, opened the first modern school (Habibia School) in Kabul, and showed a cautious openness to technological innovations.

Habibullah also maintained Afghanistan’s neutrality in global affairs. During World War I, despite German and Ottoman efforts to draw Afghanistan into the conflict on the side of the Central Powers, Habibullah resisted, adhering to a policy of neutrality to preserve sovereignty and avoid British retaliation.

Pressure mounted inside the country from nationalists and reform-minded elites who took the war as an opportunity to assert full independence from British influence. Habibullah’s assassination in 1919 created a power vacuum, and his son Amanullah Khan seized power amid internal political turmoil.

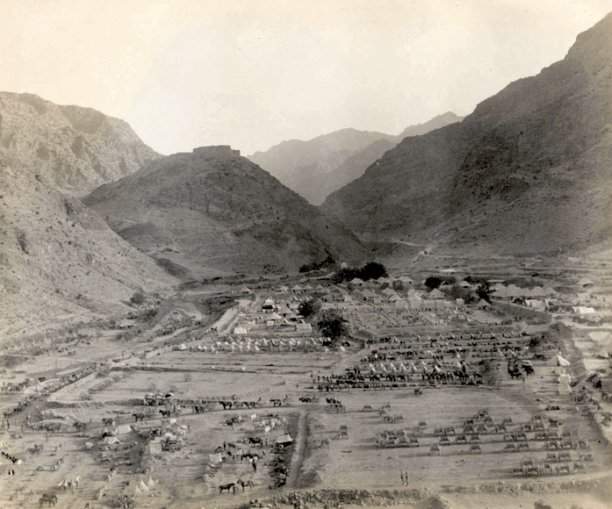

British reinforcements at Ali Masjid, mid-way in the Khyber, 1919,

Unknown photographer – Out of copyright

Shortly after ascending the throne, Amanullah launched the Third Anglo-Afghan War in May 1919. Taking advantage of post–World War I exhaustion in British India and growing nationalist sentiment at home, Amanullah declared Afghanistan’s independence in foreign affairs.

Though the war lasted only a few weeks and ended in a military stalemate, it culminated in the Treaty of Rawalpindi, through which Britain recognised independence in external relations, so ending the Afghans protectorate status.

Thus, the period from 1895 to 1919 was one of significant transformation for Afghanistan. It marked the slow but deliberate transition from a buffer state caught between empires to a modernising kingdom asserting its sovereignty on the global stage.

Back to Afghanistan

As those dark clouds gathered over Afghanistan at the tail end of the second decade of the 20th century, after a pause of 24 years, the Worth-Sayings stirred once more into action.

Being hill and lake men and having been sent to Waziristan between 1890 and 1895, this time around our local regiment — with my grandfather in tow — headed for the North-West Frontier Territory of British India, which today would be Pakistan.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the Border Regiment had several battalions, including both regular and territorial units. The 1st Battalion, stationed in British India, was assigned to the arduous task of patrolling the North-West Frontier, a region characterised by tribal unrest, harsh geography, and frequent skirmishes with Pashtun tribes.

These duties required constant readiness and exposed the soldiers to guerrilla warfare, ambushes, and prolonged field operations in remote, mountainous territory. This experience in irregular warfare would prove useful in the coming years.

My grandfather was a member of the 2/4th Border Regiment, one of the territorial units, formed at the outbreak of World War One for home service. At first stationed on Salisbury Plain, they set out for India in December 1914 and found themselves based much of the time in Peshawar, at the more peaceful end of the Khyber Pass — a frontier with Afghanistan simmering with unrest.

Indian Army picquet overlooking the Khyber Pass, 1919,

Unknown phototgrapher – Out of copyright

A carry-on in the Khyber

In 1919, the Third Anglo-Afghan War broke out when Amir Amanullah Khan of Afghanistan declared independence and an Afghan force invaded India. The Border Regiment units stationed near the Khyber Pass and other strategic points were mobilised at once.

Though the war was brief, it involved intense fighting along the frontier, with British and Indian troops launching retaliatory strikes into Afghan territory. The regiment’s knowledge of the terrain and tribal dynamics made it a valuable component in these operations.

In May 1919, the newspapers were reporting the Afghan concentration along the whole of the front becoming very pronounced, with British concentrations east of the Khyber Pass. Impressive forces of Afghan regular troops, well-armed and equipped and in every way formidable opponents, had been brought up.

The Amir’s attempts to raise the border tribes against the British had been only partly successful. The assumption being some tribes wavered in order to throw their lot in with the side which gained the first success in the inevitable coming struggle.

Regimental diaries have survived. For the territorials, they relay a dizzying back-and-forth, doing various tasks in support of other units along with some direct contact with the enemy.

One such expedition by the regiment was as part of a force dispatched from Peshawar to relieve Thal, a British garrison guarding the Kurram Pass, besieged by Afghan forces as the shooting war broke out.

According to our friends at the National Army Museum, this was the largest Afghan attack of the conflict. In the kind of complicated muddle that continues in that territory to this day, the situation became critical when the militia in adjacent Waziristan, stirred up by the Afghan government, mutinied against their British employers.

The museum website informs us,

‘Major Guy Hamilton Russell, commander of the South Waziristan Militia, made a fighting withdrawal with 300 loyal men from Wana to Fort Sandeman between 26 and 30 May 1919. During their retreat, they sustained 40 men killed and wounded. Of the eight British officers, five were killed and two (including Russell) were wounded.’

The garrison at Thal, which guarded the Kurram Pass, was soon cut off and besieged by an Afghan force under the command of Nadir Khan. The force, consisting of four under-strength battalions of Sikhs and Gurkhas and a squadron of cavalry, held out for a week until relieved by a column from Peshawar.’

That column included soldiers from the Border Regiment and was led by Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer.

Photograph of Reginald Dyer,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Troublesome India

Following the war, unrest persisted in the form of tribal uprisings and growing nationalist agitation within India. The Border Regiment maintained law and order in regions where British authority was being challenged, not just by Afghan irregulars but also by Indian political movements that gained momentum after World War I.

Anti-British momentum increased not least because of the alleged actions of the aforementioned Brigadier-General Dyer. For the month before he led the successful relief of Thal, on 13th April 1919, Dyer was in command at Amritsar when his men opened fire on a hostile crowd after days of murderous native unrest in the city.

Recollections vary. At first called the Amritsar Massacre, but since escalated to a religious significance by being renamed the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, the BBC claims 500–600 died. Wikipedia puts the total at 1,200. A number not supported by the text linked to an accompanying footnote.

The official death toll was 379. However, this figure is also disputed, not least via a loud stage whisper from Prince Philip when visiting Amritsar with the Queen in 1997 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Indian independence.

‘Vastly exaggerated’ was the phrase used. HRH and Brigadier Dyer’s son were together as cadets in the Royal Navy before World War II. Therefore, the Prince knew of the history of the subcontinent from close hand – as if a Worth-Saying!

© Always Worth Saying 2025