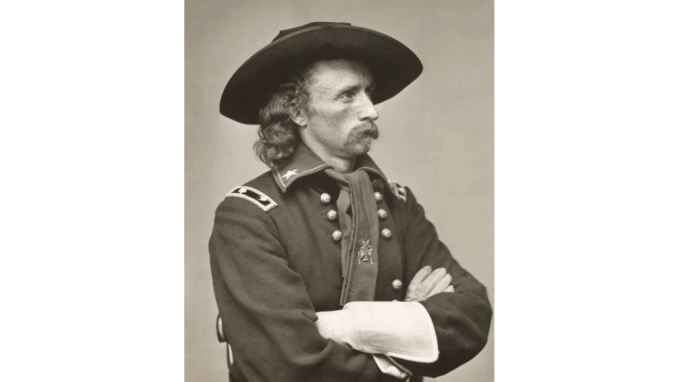

George L. Andrews, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Writing another biography of Custer (1839-1876) is, as Stiles says, a bit like walking round Grand Central Station trying to find a piece of floor someone hasn’t already stepped on. Such is the fascination with this enduring icon that studying Custer has almost become an academic discipline in itself (there is even a book about it, called ‘Custerology’). Stiles concluded the only way to proceed is not necessarily by unearthing new facts, although new insights from the archives may indeed emerge along the way, but by a change of overall perspective, emphasis or tone. He has certainly achieved this, triumphantly. The subtitle says it all: ‘A Life on the Frontier of a New America’.

This work is so magisterial it’s difficult to know where to start – you just want to keep quoting from it. With his prim, almost sharp little face, slightly dandified ginger-blonde hair and piercing blue eyes, George Armstrong Custer (‘Autie’, to his family) has been a source of myth and fascination ever since the the Seventh Cavalry débacle at Little Big Horn – possibly precisely because no-one survived to tell the tale. Little Big Horn, part of the Great Sioux War of 1876 (also known as the Black Hills War) formed part of a series of battles between the Lakota Sioux, Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne and the ultimately victorious government of the United States. The government wanted the Black Hills because gold had been found there.

Stiles gets inside the man’s psychology more thoroughly than anyone has before. The basic premise is that Custer was one of the last – perhaps the last – well-known military man to belong to the previous era: the era of the Civil War, young swells on the make, gentlemanly conduct (in public, at least), dashing cavalry charges, southern belles and wild drinking parties. The two main US political parties, pre the founding of the Republican Party in 1854, were the Whigs and the Democrats. The Whigs believed in the marriage of money, top families and power to advance a commercial agenda through banking, large, corporations, public works and government-sponsored initiatives, while the Democrats under Andrew Jackson opposed what they saw as ‘aristocracy’ and ‘monopoly’, favouring instead a meritocratic society where all could rise according to their own merits and not just by government patronage. The collision of these two worldviews was to have huge consequences. The nascent America Custer faced, of rapid economic progress, social change, emancipation and industrial revolution, saw and did things quite differently from the old antebellum days he grew up in, even as it bore him along on its relentless stream.

A man’s man who was also perennially popular with the ladies, a gung-ho hero who nevertheless had an artistic and literary bent, ‘Autie’ Custer embodied a matrix of contradictions in almost every regard. He chafed at the military regulations of West Point, and was court-martialled twice in six years. He was competent yet erratic. He had a lot of time for the Indians and their culture, yet ruthlessly put them down whenever required to do so. He was for the freeing of slaves, but vigorously opposed the idea of racial equality. He had something of a self-destructive streak. He loved theatres and shows, yet was equally at home camping out in the middle of nowhere. He visited prostitutes and drank vigorously in his youth, delighting in flirting and cavorting with showy young girls, yet married an quiet, intelligent, well-educated woman, judge’s daughter Libbie Bacon, and idealised his wife post-marriage – if you don’t count his Indian mistress, that is; a mistress who, Cheyenne sources say, was able to give him a child – something that Libby never managed. However, the Custers’ saucy letters to each other make clear their marriage was a very physical one – and there is also some evidence that Custer himself might not have been able to have any children, and a suggestion that Monasetah (his Indian mistress)’s child was actually fathered by Custer’s brother, Tom. (After Autie’s death, Libbie – who was left almost destitute – became the chief custodian of the Custer legend: she abandoned the plains and went out East, living on Park Lane in New York, where she died in 1933. Commentators noted she managed her money better than her husband ever did). Above all, in a turbulent, ever-changing time, Custer still managed to be a contrarian individualist who, while working for the foundation of the nation, embodied the chaos of his times.

As his best friend’s best man (they had ended up on opposing sides during the Civil War), Custer had been told jokingly by the bride on the wedding day that ‘You should be on our side – you should join our army’. Custer asked how much they would pay him, to defect from North to South. ‘Surely you are not in earnest?’ she, disconcerted, then replied. Maybe he was. He had been at work, one way or another, from the age of nine.

Most books, as Stiles notes, see the General as ‘a man on the march to Little Bighorn, or a glorified corpse thereafter’. This book doesn’t give you that Custer – this one gives you a living, breathing man of flesh and blood. Impulsive, romantic individualistic, the trained killer with the girlish face which won him the name of ‘Fanny’ at military academy leaps off the page. You really get under his skin and feel you are riding out on the plains alongside him, sharing a bivouac with his fellow men or standing earnestly in front of Congress giving testimony on how the South should approach the the management of freed slaves. In this biography, Little Bighorn – rather than being the main event – is seen as an epilogue. The tragedy of that engagement widens to reveal that Custer, the hero or the villain according to how the times judging him shift, never really belonged in the modernity he helped create.

‘Custer’s demons were his own, but also his contemporaries’ and ours as well’, we are told, at one point. ‘His achievements shaped our past and present … In his own bedeviled way, he confronted questions still asked in the twenty-first century: what do equality and humanity mean? Is there room for the individual in an organizational society? When does individuality become mere selfishness? How can a minority’s distinctiveness and autonomy survive amid a mass-market, globalised culture? How to cope with a time of dramatic change? Does the hero still live? … Custer’s story begins with its ending, and it never ends’.

Fascinatingly, a year after this book came out a two page letter in pencil came up for auction. The Daily Express reported: ‘An auction house spokesman said: “This is a vivid on-the-spot report from Otho Michaelis, describing, in vivid detail, his discovery of Custer’s body.

“The 7th Cavalry’s chief of ordnance emotional letter was sent to his wife and also described the terrible battlefield scene he witnessed.

“Interestingly Michaelis, who was a close friend, places the blame for the debacle at the Battle of Little Bighorn squarely on Custer.

“It’s a fascinating account from an immensely pivotal moment in history. “We expect significant interest when the letter goes under the hammer.”

T.J. Stiles won the Pulitzer Prize for this in-depth study of Custer in the context of his own turbulent times, and it was shortlisted for several other awards as well. It is a masterclass in showing how a man’s personality can play a part in the inexorable shaping of his destiny.

Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America

© foxoles 2025