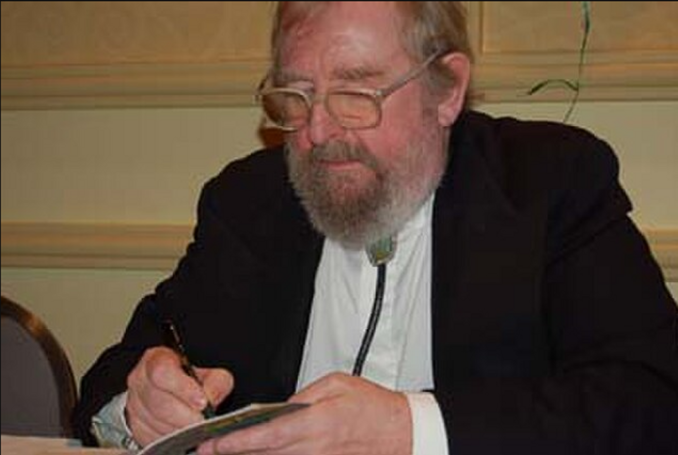

Catriona Sparks, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This article will be a short review of quite possibly my favourite romance novel. But before we get to the soppy bits, we need to set the scene by wading through some good ol’ blood ‘n’ guts.

When a young Ivory Cutlery was a mere cutlet, back in the 60s, he was also a voracious reader. I think the Commando comic book series was the first to grip me. But like so many young lads at the time, I soon became a hopeless devotee of the very fashionable 1960’s sword and sorcery pulp fiction genre. And let’s be honest here – it was quite probably the scantily clad (and usually voluminously buxom) Amazonian young ladies who adorned the covers of these paperbacks that first caught my attention. Nevertheless, raunchy covers or not, I was soon firmly addicted to the contents within.

Before long, my author of choice was one Michael Moorcock Esq. and his dark and sprawling Eternal Champion series, episodes of which he seemed to churn out with impressive regularity. Moorcock is an English author, renowned primarily for his work in the fields of science fiction and fantasy (though he has worked successfully in a number of other fields) and has the distinction of being the only author to get me chucked out of a bookshop – on Canvey Island, as it happens.

I had popped into the shop to make polite enquires as to the availability of any new works by my favourite author, only to become confused by the extremely unfriendly reaction of the very prissy lady-of-a-certain-age behind the counter. She flushed, look appalled and all but forcibly evicted me from her shop. Puzzled by her apparent outrage and indignation, I mused on my behaviour and wondered what I could possibly have done to trigger such a reaction. It was quite some time before the penny dropped and I realised she thought I’d asked if she had any more cock books? From that point on, I made quite sure I used the author’s full name when making similar enquiries.

Anyway, Mr Moorcock was a bit of a prodigy and certainly had the bit between his teeth from an early age. He was a published author and magazine editor by the tender age of 17, and his big breakthrough came in the early 1960s when he became editor of New Worlds magazine – the flagship journal for Britain’s new wave of young gun authors who, at that time, were busy with literary experimentation, social commentary, kitchen sinks and ever-more unconventional narrative forms.

Moorcock’s famous creation of this period was a sword and sorcery character who became known as The Eternal Champion, a chap (most of the time) who proceeds to swashbuckle and slaughter his way across the multiverse. This was exciting stuff for a young lad and I devoured each and every novel in the series as soon as I could lay my sticky juvenile paws upon them.

Moorcock’s Eternal Champion is, to all intents an purposes, immortal (although the character usually doesn’t know this) and inhabits various heroic (more often anti-heroic) characters across a vast multiverse, often simultaneously, in a sort of one-soul-many-bodies kind of set up. Although, once again, Moorcock’s champion is usually unaware that he has multiple existences.

By far the most popular of these characters was the doomed and thoroughly miserable Elric of Melniboné – a brooding, albino sorcerer-warrior who went around wielding a thoroughly nasty, soul-sucking sword called Stormbringer. Lots of blood-curdling adventures followed as Moorcock used his anti-hero to blend the usual sword and sorcery tropes with existential philosophy, tragedy and some damn fine ripping yarns. His output was substantial (over 100 novels and countless short stories were frenetically churned out) and I lapped them up.

However, by the 1970s, Moorcock’s reputation was secure, his publishing pace slowed and he began to spend more time crafting his novels – and I’m very happy to say the quality of his work increased accordingly. It was during this period that he released the subject of this review, his Dancers At The End of Time trilogy.

Cards on the table, I think it’s a wonderful piece of work. Not his best – I’ll probably take a look at that in another review – but it’s a dazzling, decadent romp; blending science fiction, romance, fantasy, dry wit and biting satire; and for me, at the time, it stood head and shoulders above anything the author had previously produced. These day it’s available as a single tome, but the original trilogy was comprised of An Alien Heat (1972), The Hollow Lands (1974), and The End of All Songs (1976).

In sharp contrast with much of his earlier dark and doom-laden works, this series is one of Moorcock’s most playful, showcasing his ability to fuse high-concept ideas and emotional depth with romance and exuberant fun. It’s Moorcock’s love letter to decadence, dandyism, Ronald Firbank, Oscar Wilde and, in particular, The Yellow Book – a quarterly literary periodical that was published in London from 1894 to 1897. It’s also a splendid showcase for Moorcock’s knack of subverting genre tropes and I genuinely suspect that after a decade of doom and gloom, death and slaughter, chaos and catastrophe, he just wanted his characters to have a bit of fun for a while.

The trilogy unfolds across the spectacular canvas of a distant future where Earth’s inhabitants are, to all intents and purposes, immortal and omnipotent. They inhabit an amoral and hedonistic paradise at the end of time. A nihilistic existence powered by vast, incomprehensible technologies, of which they have little or no knowledge.

Time and space are mere playthings, reality can be bent to passing whims, and the inhabitants of this playground spend their days staging elaborate parties, creating absurd art and indulging their fleeting obsessions. Around them the universe is quietly winding down, sucked dry by the vast technologies that support their absurd kaleidoscopic lifestyles. Moorcock’s setting for these novels is a triumph – an ever-shifting tapestry of surreal landscapes, sentient cities and whimsical creations, all blended with the aesthetic excess of the 1970s counterculture in which these novels were crafted.

Into this chaos tumbles Mrs. Amelia Underwood, a prim Victorian woman, unwillingly plucked from the comfort and conformity of her conventional and morally secure domestic existence in the London of 1896. Her arrival at the end of time triggers a sparkling narrative that playfully skips between comedy, farce, adventure, romance and philosophical musing.

The trilogy opens with Jherek Carnelian, a naive yet charming dandy, who becomes enamoured with Amelia after her abrupt arrival at the end of time. Jherek, entirely unfamiliar with any genuine emotion in his shallow and superficial existence, decides that he’s in love – a concept he treats as a fashionable game – and sets off in pursuit of “his Amelia”, who is quite frankly horrified by the end of time’s amorality and nihilism. This neatly sets up the clash of sensibilities that underpins the three volumes: Victorian restraint versus rampant hedonism.

Moorcock’s prose sparkles with dry humour and vivid imagery, painting Jherek’s world as a glittering absurdity, and Amelia’s fish-out-of-water perspective grounds the story within a coherent cognitive framework for the reader. Jherek’s earnest cluelessness makes for an endearing anti-hero (he’s evidently an aspect of Moorcock’s Eternal Champion – though this is never explicitly stated) and Moorcock gleefully treads a light and satirical path, introducing the trilogy’s central characters and the first volume’s central tension: can anything of true value or meaning emerge from a world devoid of any meaningful consequences?

The second volume, The Hollow Lands, sees a reversal of roles and takes place in 1896. This is by far the most comedic of the three volumes, with misadventures and larks-a-plenty in Victorian London. It contrasts sharply with the opulent sprawl of the first book and grapples with tensions between duty and desire.

The second volume continues the romance of the first, but the author wisely gives it a sharper, bittersweet edge; and Moorcock’s satire sharpens as well, poking fun at both Victorian prudery and the end of time’s vacuous and hollow excess. The pacing tightens in this volume: the first languidly lays out the landscape of the trilogy, while the second concentrates on the interplay of cultures, which are beautifully explored. The Hollow Lands also introduces the escalating stakes that comprise the bridge to the final volume.

The trilogy concludes in The End Of All Songs with Jherek and Amelia reunited at the End of Time. Their story matures as the chaos around them increases. There are subplots a-plenty, but they are not padding, and are all woven beautifully into a satisfying conclusion.

This final volume is easily the trilogy’s most ambitious, artfully balancing slapstick with existential weight. The prose remains a delight, laced with Wildean flourishes and Moorcock’s laconic signature wit and love of irony. This final volume explores themes of identity, purpose and the human condition, and the bittersweet resolution feels appropriate, though some critics at the time found its cosmic machinations somewhat overwrought.

The star of the show, for me at least, is the beautifully drawn character of Mrs Amelia Underwood. Her character develops from simple one-note prudishness into the most interesting of Moorcock’s cast. Her most profound influence is on the character of Jherek, slowly transforming him from a shallow fop, who views her as little more than an exotic plaything, into a character capable of nobility and self-sacrifice.

Beyond Jherek, Amelia deeply influences the broader society at the end of time. Characters who initially mock her rigid moral framework become unsettled by her authenticity. She becomes the mirror that reflects their emptiness; a short-lived mortal with more substance than their immense power could ever muster. Of course, Amelia’s influence on Jherek becomes reciprocal: as she teaches him depth of character, he teaches her (at least some) freedom from the constraints of her conventional Victorian upbringing; and it is this mutual evolution of character that provides the trilogy’s emotional core, elevating it from satire to a genuinely touching (if somewhat quirky) romance.

Stylistically, the trilogy is a feast – lush, witty, with theatrical flourishes aplenty. It’s a genuine oddity in Moorcock’s canon, but the author (IMHO) pulls it off with considerable style and aplomb. His dialogue throughout crackles with wit, satire and even the occasional good ol’ 1970’s double entendre; and his world-building, although on a grand scale, is wisely broad-brush, impressionistic rather than rigorous, atmospheric rather than analytic, prioritizing mood over logic. This stylistic looseness could easily frustrate the kind of reader who craves plenty of rock solid, hard tech, sci-fi coherence, but it perfectly suits the trilogy’s dreamlike and often fairytale tone.

Fans of Moorcock’s darker works (such as the Elric series discussed above) were often unkind to this work, with many finding it too light and too frivolous. But, for me, the charm and indeed the beauty of this trilogy lies in its levity and its lightness of touch – it’s a wonderfully judged counterpoint to his brooding and often darkly brutal tales of the multiverse.

Moorcock’s Dancers at the End of Time is a genuine ’70s oddity, but, unlike much from that decade, it has aged very well. As Moorcock continued to spread his literary wings beyond the simple sword and sorcery novels of his youth, this work became less and less of an outlier in his considerable canon, and now sits very comfortably in his diverse bibliography. It’s certainly not Moorcock’s most profound work, but it absolutely is his most fun – a romantic ripping yarn that gleefully pirouettes through the vast canvas of a dying universe – and I, for one, am very happy to commend it to the house.

© Ivory Cutlery 2025