Myself and my wife fussed over our Kitkats and coffees and peeled off the Standard Premium antimacassars to make it look as though were travelling First Class. Little did we realise our day trip to Birmingham was taking place in a nation on the cusp of catching fire in Enough Is Enough and Protect Our Children protests and disturbances. My pen having over the previoius few weeks distracted to those momentous events, one’s obliged to return to a middle-aged couple’s ‘six hours on the train and two hours wandering about’ excursion to the Black Country.

But first some background with the assistance of my eager intern Miss Chat, a worthy successor to my former pupil, Master AI Bot. Birmingham’s history dates back over a millennium. Its origins can be traced to the Anglo-Saxon period to a small settlement called Beorma’s Ham, meaning “Beorma’s home.” The Domesday Book of 1086 records Birmingham as a tiny village of little significance, but its strategic location would soon foster rapid growth.

During medieval times, Birmingham evolved into an important market town. The de Birmingham family played a crucial role in this transformation, securing a charter in 1166 which established the town as a hub for trade. The local market and fair attracted merchants and artisans, contributing to a burgeoning economy based on metalworking and wool. In the 16th century, John Cooper received the right to bait bulls on the green within the Corn Cheaping market.

The 16th and 17th centuries marked Birmingham’s rise as a centre of metalworking and manufacturing, a tradition that would earn it the nickname “The Workshop of the World.” The Industrial Revolution catapulted Birmingham to global prominence. Innovations in steam power, the establishment of the canal network and advancements in metalworking industries transformed the city into a powerhouse of industrial activity. Pioneers like Matthew Boulton and James Watt were instrumental in these developments. Their Soho Manufactory became a beacon of innovation.

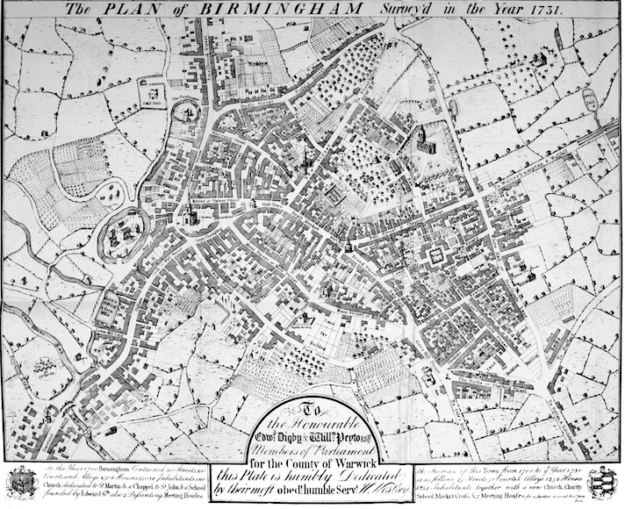

The Plan of Birmingham Survey’d in the Year 1731,

John Alfred Langford – Public domain

The 19th century further cemented Birmingham’s status as a manufacturing titan. It became a hub for a diverse array of industries, including textiles, food processing and chemical production. The city also experienced significant population growth and urban expansion, with new housing and infrastructure accommodating the influx of workers. Social reformers like Joseph Chamberlain played pivotal roles in modernising the city and improving sanitation, education and public services.

The 20th century brought both challenges and transformation with the city suffering significant damage during World War II. Throughout the conflict Birmingham played a crucial role in the war effort, becoming a focal point for manufacturing and munitions production. Birmingham’s manufacturing infrastructure adapted to meet wartime needs. Factories that once produced vehicles and household goods repurposed to manufacture aircraft, tanks and weapons. The Austin Motor Company, for instance, shifted from car production to making military vehicles and aircraft components.

This strategic importance did not go unnoticed by the Luftwaffe. The city experienced intense bombing campaigns – remembered as the Birmingham Blitz – between 1940 and 1943. The most devastating raids occurred in November 1940, when a series of night-time bombings caused destruction far and wide. A flavour of the times comes from an old newspaper cutting dated 10th April 1941,

“Birmingham last night was the target of intense attack. Widespread damage resulted and commercial buildings suffered, while many people were rendered homeless. Extensive damage was caused by fire to shops. Casualties, it is feared, will prove heavy, and rescue work is still proceeding. At first, lone planes roamed over intermittently scattering incendiaries. Later, large waves of bombers hailed down a rain of incendiaries and scores of high explosives.”

Post-war Birmingham faced the daunting task of reconstruction to restore housing, infrastructure, and industry – with mixed results. The latter half of the century witnessed the decline of traditional manufacturing industries, prompting economic diversification and regeneration efforts. The Bull Ring Shopping Centre opened in 1964. Half a century later, the developers struck again with both the Bull Ring and New Street Station being re-built. During our day trip, the city centre was peppered with building sites.

Noticeable among the scaffolding and bags of cement are cultural investments such as the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery which houses an impressive collection of pre-Raphaelite artworks. Nearby are the Birmingham Royal Ballet, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and its Symphony Hall, the Birmingham Rep and THAT library. However, Puffins will realise these things cost money rather than make money. Puffins will also be aware Birmingham City Council is bankrupt. Even the Hippodrome on Hurst Street, one of the busiest theatres outside London, is not in the private sector but a theatre trust and registered charity reliant on grants.

© Always Worth Saying 2024, Going Postal

In terms of private sector economics, Birmingham has moved from its traditional manufacturing roots to a diversified economy. It is a hub for finance, with the presence of major banks and financial institutions, including HSBC. A business district is centred around Colmore Row. Higher education plays a role through the University of Birmingham, Aston University and Birmingham City University.

The city’s transport infrastructure has seen substantial investment – there are trams – including the redevelopment of New Street Station. The planned High-Speed 2 (HS2) rail project promises, at vast expense, to reduce travel times to London and other major cities. The terminus is being built at Curzon Street, less than half a mile from New Street. According to Wiki, travel to London, albeit Old Oak Common, will take 49 minutes as opposed to the 76 minutes on the fastest present-day service to Euston – a saving of 27 minutes at a cost north of £60 billion.

The modern-day population is about 1.14 million people, making it the second-largest city in the United Kingdom after London. Birmingham’s population is characterised by a younger more ‘diverse’ demographic. A significant proportion of residents are under the age of 30. According to the 2021 census, over 60% of Brummies come from various ethnic minority backgrounds, including large communities of South Asian, Black, Caribbean and Eastern European descent.

The port of entry when arriving by rail from the North is New Street. Opened in 1854 by the London and North Western Railway (LNWR), New Street replaced several smaller stations to consolidate Birmingham’s rail traffic. The station’s initial design featured a vast single-span iron and glass roof, the largest of its kind in the world at the time.

By the middle of the 20th century, the station had become congested due to rising passenger numbers and freight traffic. This necessitated a significant expansion and modernisation project completed in 1967. The redevelopment included a new concourse and the construction of the Rotunda. Despite this ‘improvement’, the station’s underground design led to complaints about its dark, cramped, and unwelcoming atmosphere.

In the early 2000s the Gateway Project aimed to address these issues. Completed in 2015, a £750 million redevelopment revolutionised the station’s architecture and functionality. According to the guff, the new design features a ‘spacious, light-filled concourse thanks to the addition of a grand atrium and extensive use of glass’. The station’s exterior is clad in a reflective steel facade, giving it a ‘modern, futuristic appearance’ as if an outsized squashed tin can.

The redevelopment also includes Grand Central, a shopping and dining complex located within the shiny can. Beneath this, over 140,000 passengers a day pass through the station, including my wife and myself early one Thursday afternoon in July as we emerged from an escalator onto the central concourse slack-jawed and blinking. Usefully for country bumkins like ourselves, the station is divided into coloured zones. Note to the uninitiated: make a note of the zone you’ve arrived in, it will make it easier to find your way to the correct platform for your departure. But before then, Birmingham awaits!

© Always Worth Saying 2024, Going Postal

First we noted the diverse nature of the population. Remember North Country raconteur and wit Bernard Manning’s day trip trip to Bradford? Like being the spot on a domino? Quite. The second thing to catch our attention was the giant bull. He has a name, Ozzy, and is the former centrepiece of the city’s 2022 Commonwealth Games Opening Ceremony. Standing thirty-three feet tall and weighing 2.5 tons, Ozzy is a larger-than-life mechanical bull crafted by a team of over 50 artists, engineers, and puppeteers.

With glowing red eyes and smoke billowing from his nostrils, Ozzy made a dramatic entrance into the Commonwealth Games stadium. Guided by a group of female chain-makers he evoked the city’s role in the fight for workers’ rights and the emancipation of women in the workforce. After the opening ceremony, Ozzy sat in the city’s Centenary Square for the duration of the games before being moved to a derelict part of a car park off Great Tindall Street to await dismantling. However, a public outcry saved the unemployed male Brummie and a new home was found in the station.

Relocated to the New Street concourse, Ozzy was unveiled in front of then mayor Andy Street, boxer Delicious Orie and Sharon Osboune – after whose rock star husband the beast had been named after a public ballot. Amidst the brass band music and face painting, Sharon told the assembled that the other Ozzy was thrilled to bits. When a fledgling pop star, he couldn’t drive and often travelled on the train to and from New Street.

Mechanical Ozzy’s head and tail swished until a mechanical problem last March put him out of action. During our visit he stood motionless. As we shall see, not the only thing that is wrong with England’s second city.

To be continued…

© Always Worth Saying 2024