“The record of what one man saw and heard and felt on a journey through Britain in October 1947, by John Alldridge”

Uncle John’s record of his trip round Britain, to assess the extent to which the nation was recovering a little more than two years after the end of the War, first appeared in the Manchester Evening News. Sadly, a few of his articles have been cut short as the original copies were corrupted in the archive process – Jerry F

Chapter 4 – What Clydeside wants to know…

Clydebank

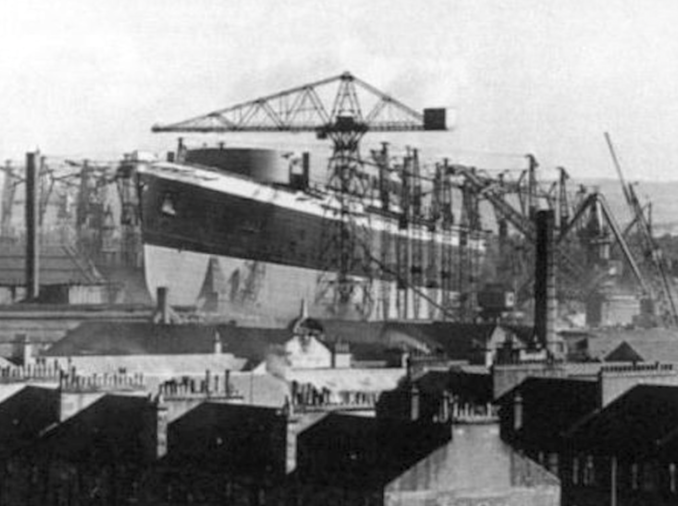

From where he sits in his carved chair at the head of the boardroom table Sir Stephen Pigott, director-in-charge of John Brown and Company, shipyards and engine works, can just see the proud white bows of his new 35,000-ton liner towering above the slipway.

He has been watching her grow for over two years, and one gathers that he will not be sorry when, on the thirtieth of this month, and at exactly midday, Princess Elizabeth names her Caronia and starts her off on her slow tow up to the fitting-out wharf. For she has taken half as long again to build as it took to build a ship of her size before the war.

RMS Caronia in 1956,

Oskar A. Johansen/Municipal Archives of Trondheim – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The giant Queen Elizabeth, growing on the stocks.,

The Great Ocean Liners – Public domain

They don’t give much away at John Brown’s. Visitors aren’t welcome. And even Sir Stephen Pigott, for all his old-world charm (he looks and talks rather like old Jolyon Forsyte, though he was born in Cornwall, New York), would be reluctant to admit that the two real factors which are holding up his building programme are a shortage of raw materials and a lack of interest in their work shown by too many of his 8,000 employees.

There are half a dozen ready reasons for the shortage of materials — which extends all the way from sheet steel, irregularly delivered, to locks for cabin doors (and there is a particularly acute shortage of electrical fittings). An explanation for a falling-off in enthusiasm is not so easy to find, though it is just as serious.

But half an hour’s conversation with John Ferguson puts you on the right track. You can find John most lunch hours these cold mornings warming his back against a brazier which smokes fitfully almost directly under Sir Stephen’s office windows.

John Ferguson is a skilled fitter, a small withdrawn little man, who looks more like an unsuccessful jockey than a shipyard worker. His latest spell with John Brown’s has lasted seven years. During the slump years, when grass sprouted knee-high in these yards, he bought an insurance book from his brother-in-law and made a good thing of it.

The war brought him back to the yard and for five years he rarely earned less than £9 a week. Today he is earning £4 19s. a week with an occasional bonus of a few extra shillings.

Contented enough with his lot during the feverish, exciting years of war he is now full of irritations which in normal, happier times would never occur to him. As in the pits at Seaham, here was the same old miserable dirge as dog ate dog. Why should he, a skilled fitter, get less than half the wage of a riveter or a plater?

Last week the yards began working staggered hours so that the electricity load along Clydeside could be lightened. This meant that though the day-shift workers at John Brown’s now get Monday afternoon off they have to work instead on Saturday morning. Wasn’t this just another instance of victimisation he wanted to know? And it brought a disgruntled chorus of agreement from other men warming their hands.

He agrees that even if he had Saturdays off and received his wartime wage there would be little opportunity to enjoy either. But is that any reason why he should freeze to death at the end of a rope in a December frost for a miserable five pounds a week while other men can make comfortable fortunes selling rotten fruit from barrows? Once it was “blackleg” and “scab” on Clydeside. Today it is “spiv.”

But the biggest cause of discontent exists outside the yard. No town in Britain was more cruelly blitzed than Clydebank. Two night raids in March, 1941 damaged all but eight of the town’s 11,835 houses. More than 4,000 were completely destroyed.

Today a town with a pre-war population of 50,000 contains barely 38,000 souls. At the end of the day many workers — John Ferguson among them — are faced with a long tram ride back to their temporary homes in Glasgow.

Chapter 5 – The Men of Steel

Sheffield

Attercliffe is the sort of grimy little suburb which you find tacked on to the east end of every big manufacturing city.

Not an attractive place, Attercliffe; its salient features are a range of grey slag heaps, a greasy canal, a railway siding and a great number of corner pubs and beer houses. It is the last place in the world where you would expect to find artists following a highly skilled craft.

And yet in the dingy clatter of these workshops, where they fashion everything out of steel from a hacksaw blade to a fifteen-inch gun, you find spectacled, middle-aged men in dirty overalls doing work that would not have disgraced Benvenuto Cellini.

It is easy to fall into the common mistake of thinking that real craftsmanship vanished with the generation that knew Hepplewhite and Sheraton. To correct that impression you must stand for a few minutes, as I did, and watch a man smooth the rough spirals off a bit with one sustained movement of his wrists against a buffing wheel.

It has taken him thirty years to perfect that technique. He is proud of it; there are not a dozen men in Sheffield, he thinks, who can do it as well. In another ten years, when he, with most of his generation, has retired there may not be one.

Nobody would be silly enough to claim that making steel is attractive work. It is hard work, dirty work, thirsty work and dangerous work. (Accident figures in the steel industry are higher even than in coal). But watch a steel-roller standing, feet apart, in the smoky glare of his forge, wiping the sweat from his face while he gulps down the jug of beer his apprentice has just brought over from the corner pub and you realise that this is a man’s job.

What worries Sheffield’s steel men these days — worries them even more than rising costs and uncertain supplies of fuel and the weary juggling with staggered hours — is the melancholy knowledge that the youngsters coming into the industry are not settling down to the trade as their fathers and elder brothers did before them. The complaints against them, brought by skilled tradesmen who learnt their trade the hard way, are that they lack enthusiasm, lack ambition, and are afraid of long hours and hard work.

In their defence some tolerant employers and foremen blame the war for this, coupled with a National Service Act which snatches a youngster away from his trade just when he is beginning to understand it, and returns him eighteen months later unsettled and dissatisfied, and entitled to a wage, which, judged on his skill, he is not worth.

They are worried because they know that the Sheffield steel industry — probably the most highly concentrated of all industries — depends for its life on the skill and initiative of its craftsmen.

In one workshop where sweating men were kicking about great fiery ingots, I talked to a foreman moulder.

During the war this man and his team of 11 moulders made valve bodies for battleships. Today they are making essential items like endless chains for conveyor belts and centrifugal pump casings. They are working an average 52 hours a week. But they are hopelessly behind with their work. They have a book full of orders which they know they cannot fulfil before well into 1949.

The average age of this team is 35. They are getting no reinforcements. And only a few weeks ago their last two learners left them, one to earn an easy £9 a week making magnets for wireless sets, the other to earn a guaranteed wage of £7 10s. casting pepperpots.

“It’s a wicked thing to say, mister,” said this foreman, his thin lips very bitter. “But there’s only one thing can help us here — and that’s a two-year slump.”

I remembered what I had heard a works manager tell me earlier that day. His firm makes engineers’ tools of high-grade steel that sell all over the world.

“If you were a fairy godfather and gave me just one wish, I’d ask for a labour force who knew their jobs as well, and were prepared to work as hard and as loyally, as the men we had before the war, because we just haven’t got that labour force here today.”

Chapter 6 – Between the looms

Leeds

Outside it was raining. That fine, warm Yorkshire drizzle which can turn a crisp autumn landscape into a vast grey steam bath.

But inside the mill I was enjoying myself. I was happier than I had been at any time since I set out on this journey. Up here in this display room they were pouring colour recklessly over me. Yards and yards and yards of it — delft blue and primrose and crushed strawberry and delicate brown herringbone, as soft to the touch as a baby’s cheek.

Watching that lovely stuff being rolled back into neat bales on the first stage of its journey to Fifth Avenue and the Rue de la Paix, I knew suddenly what women mean when they talk about being “colour-hungry.”

In this mill they claim to do everything but shear the wool from the sheep’s back and make the garment. They talk about wool as if it were somehow alive.

This is a good mill, one of the best in the West Riding. It was founded in 1869, and the old grey heart of it throbs as it always did to the bang and clatter of looms. But it has grown with the years and kept abreast of the times.

Now the accent is on warm red brick and clean, well-ventilated workrooms, painted in cheerful shades of primrose, white, and green and lit by shadowless fluorescent lighting. Hot midday meals are served in a modern canteen and there is a pleasant young lady welfare officer always on hand, it seems.

The manager is something of a philosopher. And something of a psychologist, too. I was praising the pleasant surroundings when he interrupted me. “A mill is only bricks and mortar after all,” he said. “And the finest machinery in the world is only so much iron and steel. It’s people that count.”

Walking round the mill with its chief designer, and noting the cheerful nods and smiles that greeted us as we picked our way between the banks of looms, I wasn’t surprised to hear that this mill, despite restrictions and controls, irksome to an industry which has grown great out of fierce competition, is actually producing slightly more cloth than in the best years before the war.

About half of this goes to foreign customers who, from all accounts, are delighted with the quality and speed of delivery even if they think the prices stiff.

But that isn’t the end of the story. I thought it was all too good to be true. For agreeable as life is in this mill, it is undermanned. I talked to a middle-aged spinner, Albert Rhodes, who has charge of a pair of mules, each mule turning 384 spindles. Albert Rhodes, in his fifties, confesses that he gets tired too easily nowadays. By rights he should have two young apprentices, or “piceners,” to help him and learn his job at the same time. It is now over a year since he lost his last “picener.’

He told me how, as a little lad, his parents put him to work under the best spinner in this mill. For the same reason, I suppose, that parents in the Middle Ages sent their sons to Paris to study under Abelard. But that is all finished now, he says. He has a pair of girls growing up. But one is training to be a hairdresser and the other is a typist in Leeds.

Afterwards I asked the manager how he explained this drift away from the mill, knowing all too well by now what answer to expect.

He blamed it on three things — on a system of higher education which, excellent though it is, tends to make youngsters despise mill work; on a deep-rooted fear of insecurity, inbred by years of trade depression; and — he didn’t want to admit this, I could see — on a tendency today to by-pass hard work in search of soft, well-paid jobs.

The question he hates asking himself is where he is going to find his experienced spinners and scribblers in ten or fifteen years from now.

There is another thing which worries him almost as much. High up on the top floor of one of these sheds, where wide windows stare down the hill to Leeds, smoking ten miles away, are the “perches” where keen-eyed inspectors examine every yard of finished cloth as it leaves the mill.

A faulty piece calls for an inquiry. It used to mean wounded pride and bitter humiliation to be “brought up to a bad piece.”

But now, they tell you sadly up there on the “perches,” it’s just like water off a duck’s back…

Reproduced with permission

© 2024 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2024