On the morning of February 4, 1954, G-ALRX took off from Filton on a test flight, with Captain A.J. ‘Bill’ Pegg at the controls.

Flight Engineers for the trip were Ken Fitzgerald and Gareth Jones. On board were Dr Archibald E. Russell, Chief Designer of Bristol Aircraft Division; dir. Stanley G Hooker, Chief Engineer of the Bristol Engine Division; and Mr Farnes, the Bristol Sales Manager.

This was not just a test flight; also present were two representatives of the Dutch airline KLM, a potential Britannia customer. G. Malouin of KLM was co-pilot for the flight. Thirteen people were on board all together.

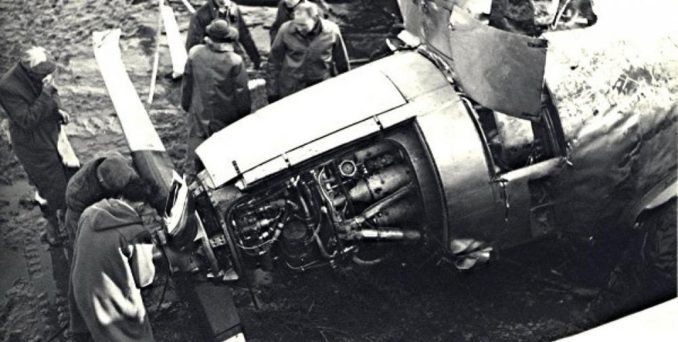

About seven minutes after take-off, the temperature in engine number three rose. The engine was shut down and later restarted as the temperature cooled and the flight continued its journey northwards to Herefordshire. While climbing to an altitude of 10,000 feet, the temperature rose again and the engine exploded. Shrapnel missed the fuselage, but pierced the engine oil tank, which burst into flames. The fire was so intense it could not be extinguished.

While Bill Pegg turned the aircraft south for an emergency landing at back at Filton, engine No.4 was shut down, as a precaution. To add to the drama, engines no. 1 and 2 shut themselves down, turning the Britannia into a large glider. It was only the speedy work of the two engineers, Fitzgerald and Jones, that got the two port engines relit, and disaster was averted.

With flames engulfing the starboard wing, threatening to penetrate the fuel tanks, and Filton still several miles away, Pegg elected to put down on the Severn Mudflats, the silt and mud of the Severn Estuary exposed when the tide is out.

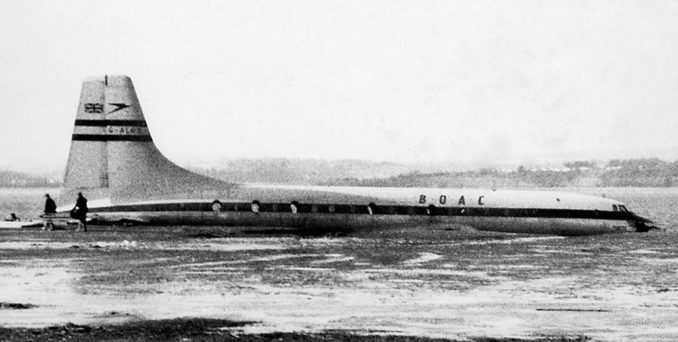

With the flaps and wheels up, and only the two port engines running, the Britannia was expertly belly landed on the flats near Littleton-on-Severn, not far from the eastern end of the first Severn bridge, which was built the following decade.

The aircraft slid for 400 yards, sending plumes of mud in the air. It ended up facing out from the shore, with one engine ripped from the nacelle, but with little damage elsewhere. Miraculously, the mud managed to put out the flames, which could have ripped through the fuel tanks at any moment. Relieved and shaken the crew and passengers jumped from the aircraft.

Locals and workers from the nearby brickworks ran to the scene to help. Fire tenders arrived but were not needed. Although only 150 yards from the shore, the aircraft could not be pulled from the mud before the tide came in. A mesh pathway was laid over the mud, and frantic efforts began to retrieve any equipment that could be saved.

It was 48 hours before an attempt could be made to pull her ashore, but the sea had taken its toll, and the aircraft was a write off. Not only had the salty water covered the fuselage, damaging the airframe and any equipment remaining on board, but efforts to pull the aircraft to the shore had put extreme stress on the fuselage.

From her first flight 43 days earlier, she had achieved only 51 hours and 10 minutes in the air, in 24 flights. With the loss of the aircraft from the flight test programme, development of the Britannia was delayed.

© Reggie 2024