Two young men, in a souped-up old Chevy, travel across the USA, making what money they can by betting on the drag races they enter. Along the way they’re joined by a lost hippie girl, and cross paths with a middle-aged man in a flashy new Pontiac GTO. There’s a challenge, and they agree to race all the way to Washington DC, the winner taking possession of the loser’s car.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

This is not really a review as such, though there will be spoilers, but, as this film doesn’t have much in the way of a plot, it probably doesn’t matter. Some of the posters for the movie had the tagline “No Beginning. No End. No Speed Limit”, and that could well be true. The characters don’t even have names. They’re known as The Driver, The Mechanic, The Girl and GTO.

In the late 60’s Hollywood was discovering that there was a “youth market” but was unsure how to go about capturing it. Producer Michael Laughlin had paid $100,000 to an actor called Will Corry for a script about two men driving across America in pursuit of a girl. He offered it to director Monte Hellman, who liked the idea, but wasn’t crazy about the script.

Monte Himmelbaum, (as he was then) had started out as a theatre director in the early 1950’s, and had directed California’s first production of “Waiting For Godot”, a bit of trivia which may or may not become relevant as we go along. By the late 50’s he had changed his name to Hellman and had started working for Roger Corman, being given his first film to direct in 1959, “The Beast From Haunted Cave”. Throughout the 60’s he worked with Corman as a second unit director and editor on numerous films, and he also directed two low-budget Westerns starring a young Jack Nicholson, which were critically acclaimed but commercial flops.

He agreed with Michael Laughlin to direct this road movie, but only if he could bring in a different writer. That agreed, he approached beatnik novelist Rudy Wurlitzer to write a new script. Wurlitzer apparently read just five pages of the original script before giving up and starting from scratch. He then immersed himself in the world of Los Angeles street racers, living in a cheap hotel room in the San Fernando Valley, and came up with a new script in four weeks.

Just then however, the production company putting up the money for the film got cold feet and pulled out. Hellman shopped the script around to whoever he could but they all wanted more control over the project than he was willing to share, and they all wanted a say in the casting. Then Easy Rider was released and became a box-office sensation, and a film about two guys in a car suddenly started looking like a good business proposition.

Ned Tanen, an executive at Universal Pictures, agreed to give Hellman $850,000 to make the film and with full creative control including final cut. This was unheard of for a major studio, and it would come back to bite them.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

Casting was the next issue. Warren Oates, who Hellman had worked with on his 1966 film “The Shooting”, was an easy choice for GTO.

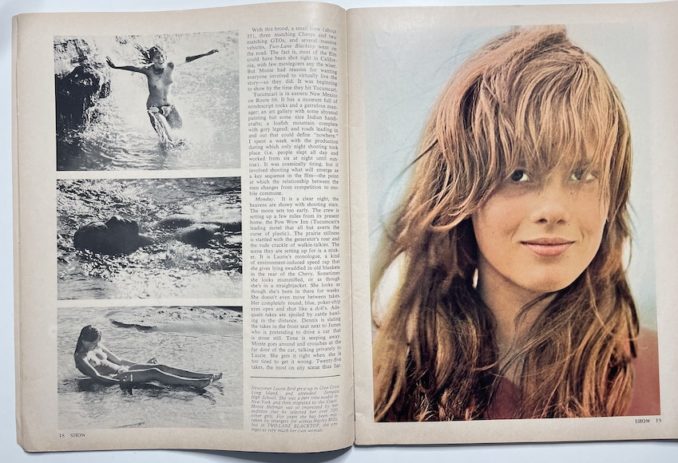

Laurie Bird was a 16-year-old hippie girl and aspiring model that Rudy Wurlitzer had been hanging out with for “research” purposes, and he suggested her to Hellman. She had no previous acting experience.

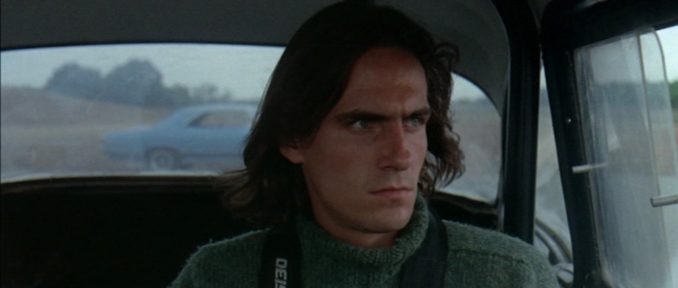

For the part of The Driver, lots of young Hollywood stars were tested, but none were deemed suitable. Driving home one day he spotted a large billboard promoting James Taylor’s first album, and said to his assistant, “That’s the kind of guy we’re looking for.”

And somehow Taylor was talked into it. Beach Boy Dennis Wilson was the last to be hired, just five days before they started shooting.

So of the four leads, only Oates had ever been in a film before.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

In other unconventional decisions, there was no make-up used on the actors, and for The Driver, The Mechanic and The Girl, they were just taken to a large charity shop and told to pick out their wardrobe. In a total break from normal practice, the film was also going to be shot in sequence, and on the actual roads across America. And the actors were never given the full script, just handed the next day’s scenes every evening.

Three almost identical 1955 Chevrolets were specially built by racing engineer Richard Ruth. Two were constructed as full-on drag racing cars, with 454 Chevrolet engines (7.4 litres). One was for exterior scenes and racing, but was too noisy for filming inside. The second had added soundproofing, and some mounts welded underneath for camera platforms.

The third car had a slightly smaller 427 (7 litre) engine, and was built for a crash scene that in the end was never filmed. Two bright yellow Pontiac GTOs were sourced from General Motors.

Filming started in Los Angeles on 13th of August 1970 and lasted for eight weeks, the whole cast and crew and a transporter with the five cars, making their way across the country, to finish in Tennessee. James Taylor was at the time in a relationship with Joni Mitchell, and she also joined the caravan from time to time.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

The cinematographer was a young man called Gregory Sandor, but as he was not a union member the studio insisted that a union cameramen be hired. So the name Jack Deerson appears in the credits, and Mr. Deerson did accompany the crew across the country, but apparently mainly stayed in his hotel room. Gregory Sandor got his name on the credits as “Photographic Advisor”. If anyone wants to know more detail, the film was shot in the Techniscope format, a cheap widescreen format using normal lenses, but with cameras modified for two perf pulldown, instead of the usual four pref pulldown. This format was extensively used in spaghetti westerns.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

And so to the film itself, well, two drifters go from town to town, betting on their car to race local hot rods. They hardly speak to each other. Somewhere in Arizona, while they’re eating in a restaurant, a girl climbs into the back of the car. At first they ignore her, but she slowly affects the relationship between the two men. At the same time, they keep passing and get passed by a bright yellow car that seems to be dogging their trail. When they finally get to talk to its driver at a petrol station an argument ensues and they set up their cross-country race.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

GTO is a middle-aged man with no clear history. He tells a different version of his life story to each hitchhiker he picks up. He’s an Air Force test pilot, he’s a television producer, he’s a secret agent… Who knows what the truth is, but it feels like he’s on the run from something.

The race itself soon dissolves into nothing. It’s not important. They help each other out on occasion. When GTO’s car breaks down, The Mechanic lends a hand, they drive each other’s cars, and GTO steps in as the boys’ manager when they enter a more professional drag race.

But they just keep moving, The Girl unsettling all of the men as they head east, and throwing their previous harmony into some disarray. Eventually she leaves them all, climbing onto the back of a random motorcycle. When there’s no room for her duffle bag on the bike, she just dumps all her belongings in a car park.

GTO heads off, and picking up some hitchhiking soldiers, this time his story is that he won his car in a race when he was driving an old Chevy he’d built himself.

The Driver goes to another drag race, but things aren’t right with him. Sitting in the car he looks off to a nearby farm and seems to have some regrets about a road not taken. He shuts the car window with a noise like a tomb closing. As he accelerates the film slows, and slows, and stops, and the film itself burns up in the projector gate.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

The film had been highly touted in the press as it was being made. The March 1971 edition of Show magazine had a large feature on it, including a lot of photos of scenes which never made the final cut.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

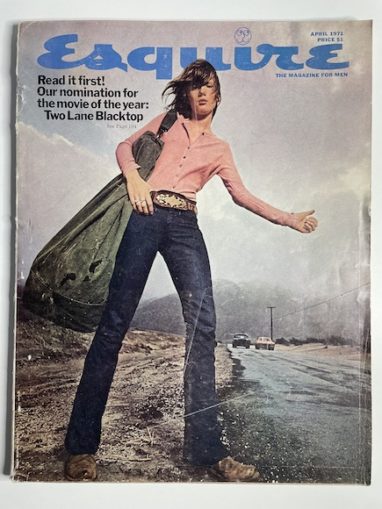

In their April 1971 edition, Esquire magazine had proclaimed it “Film Of The Year”, put Laurie Bird on the cover, and most unusually, printed the entire screenplay.

‘Read it first! Our nomination for the movie of the year: Two-Lane Blacktop – Where the road is and where it is going: the first movie worth reading.’

Universal, and particularly its CEO Lew Wasserman hated the finished film. A film about racers where you hardly see any racing. A road movie with no action. Two-star musicians in the cast who never sing. Not to mention the almost total lack of a plot, and the performances of the three non-actors. As Hellman had final cut in his contract there was little they could do about it.

Wasserman couldn’t stop the film being released but he did stop all advertising for it. The film opened on the 4th of July weekend 1971 and only ran in cinemas for a few weeks. Easy Rider it was not.

Esquire magazine did a reverse ferret and quickly turned on the film…

‘the film is vapid: the photography arch and tricky and naturally, therefore, poorly lit and unfocused; the acting (only one part is played by a professional) amateurish, disingenuous and wooden; the direction inverted to the degree that fundamental relationships become incidental to the film’s purpose. The script has become the victim of the auteur principle.’

The film disappeared. Hellman was supposed to go on and direct Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid, (also scripted by Wurlitzer) but he was replaced by Sam Peckinpah.

I first saw Two-Lane Blacktop when it popped up late one Saturday night on BBC2 in the early eighties, back when they used to show good films on TV.

It was unavailable on VHS or DVD though, mainly because of copyright issues with some of the music used in it. Moonlight Drive by The Doors was the real sticking point for some reason, and this was only resolved in the late 90s by Hellman writing to Ray Manzarek and getting him to intercede with the record company. The film was finally released on DVD and its reputation grew and grew. When Sight and Sound magazine did a poll of world film critics in 2012, seven of them chose Two-Lane Blacktop as one of the top ten films ever made. And the Waiting For Godot reference I mentioned way back at the start?

Well, here’s a link to a long article which argues that the film is a sort of Waiting For Godot on wheels, with The Driver and The Mechanic as the two principles, and GTO playing the role of time snapping at their heels.

I don’t know if James Taylor has finally seen it by now, but as of a 2007 interview he had never seen the finished film. And he’s the only cast member left alive.

Dennis Wilson drowned in 1983, aged 39.

Warren Oates had a heart attack and died in 1982, aged 53.

And Laurie Bird committed suicide with an overdose of pills in boyfriend Art Garfunkel’s New York apartment in 1979, aged 25.

I only found out while writing this piece that during the filming of Two-Lane Blacktop, Monte Hellman had left his wife and started an affair with Bird. He was 41, she was 17.

They married in 1974, but the marriage lasted just six months.

There’s a behind-the-scenes clip on YouTube of Hellman trying to convince Bird to take her top off, (probably for the swimming scenes which ended up on the cutting room floor), where he comes across as extremely sleazy.

Hellman went on to direct several more films but Two-Lane Blacktop is probably his most acclaimed work. He died in 2021 after a fall at his California home, aged 91.

Aside from everything else, because they shot on the road in real locations, the film is a great snapshot of rural America in 1970. Just don’t watch it looking for lots of action, or a plot. The film is just a slice of time, of some people going nowhere.

Fair Dealing / Fair Use

And then there are the cars.

Well the two GTOs were basically on loan from Pontiac. Hellman used one as his personal car for a few months after filming but then they had to be returned. Fate unknown.

The three Chevrolets became the property of Universal Studios, and in 1973, when George Lucas was making American Graffiti, two of them (the #1 car and the #3 car) were sprayed black and became the car driven by Harrison Ford in the movie. The stunt car built for Two-Lane Blacktop’s crash scene that was never filmed, finally got destroyed in American Graffiti’s crash.

The #2 car, used primarily for the interior shots, was discovered in 2001 in Canada. Someone had actually restored it and painted it black, thinking it was the American Graffiti car. Original builder Richard Ruth verified its authenticity, and then it took several years to restore the 1955 Chevy back into its Two-Lane Blacktop incarnation. The completed car was eventually auctioned in 2015, and it sold for $145,000.

© Maximum Overdrive 2023