Plymouth and the Blitz

Plymouth is a city located in the county of Devon. Geographically, it is positioned on the south coast and is approximately 36 miles southwest of Exeter and 193 miles southwest of London. The city lies between the Rivers Plym and Tamar, both of which flow into Plymouth Sound.

Throughout history, Plymouth has been of significant importance due to its strategic location and its harbour, known as Sutton Harbour. It was the point of departure for many historic expeditions, including Sir Walter Raleigh’s attempts to colonize Virginia and the English fleet’s attack on the Spanish Armada.

During World War II, Plymouth suffered substantial bomb damage, but it has since been rebuilt and developed into a vibrant city with bustling commercial, shopping, and civic centres. The city is also home to a range of industries, including manufacturing, chemicals, and engineering.

As of the 2021 census, the population of Plymouth was 264,700. The city also offers various self-guided tours for visitors, including the Devon Tour App, Hidden Gems Game, and Big Britain Quiz.

During World War II, Plymouth suffered significant damage due to German air force bombings. hundreds of children were evacuated. The primary target was the dockyards at Devonport, but many bombs fell on the city itself. The first bombings occurred in July 1940, leading to three casualties, and by early 1941, five raids had reduced much of the city to rubble. The bombings persisted until May 1944.

Almost every public building, including the two main shopping centres, 26 schools, eight cinemas, and 41 churches, were destroyed. In total, 3,754 houses were destroyed, and another 18,398 were seriously damaged. During these attacks, 1,172 civilians were killed, and 4,448 were injured.

One tragic incident was the direct hit on the communal air-raid shelter at Portland Square during an attack on the central area on the evening of April 22, 1941, which resulted in 72 casualties.

Charles Church, ruined by firebombs, has been preserved in its damaged state as a permanent monument to the city’s suffering during World War II – albeit marooned in the middle of a roundabout – and as a memorial to the civilian victims of the bombings.

St Andrew’s Church and the Guildhall

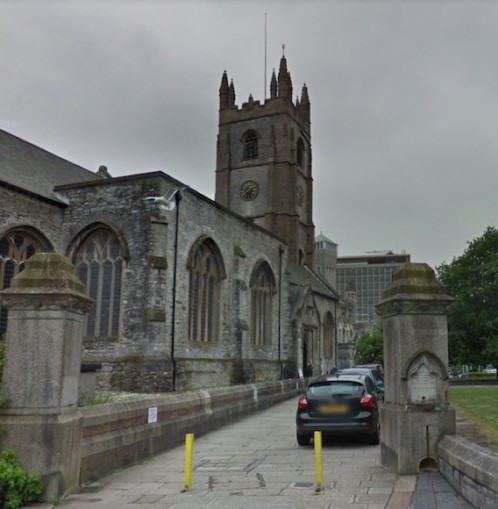

The photo taken by my grandparents during their 1947 road trip isn’t of Charles Church but of St Andrews Church and the neighbouring Guildhall.

St. Andrew’s Church is also known as the Minster Church of St. Andrew and is a significant landmark in the city. It is located in the city centre and is the largest parish church in the county of Devon. The current building dates back to the late 15th century, although the site itself has been a place of worship since AD 800.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

The church has a rich history and has undergone numerous renovations and repairs, especially after World War II when it was heavily damaged during the Plymouth Blitz. Remarkably, its fourteenth-century tower survived, standing as a beacon of hope amid the destruction.

The church was restored after the war under the guidance of notable architect Sir Frederick Etchells. The restoration followed the original perpendicular style, and the church was rededicated in 1957. The stained glass windows, installed after the war, depict scenes from Plymouth’s history, including the departure of the Mayflower.

St. Andrew’s Church was given Minster status in 2009, recognizing its significant historical and community role. It continues to play a central role in the religious and community life of Plymouth, with regular services, concerts, and community events.

The interior of the church is equally impressive, with a beautifully carved pulpit, a grand organ, and a number of historical memorials. The churchyard also contains several war memorials, including one dedicated to the victims of the Blitz.

The Guildhall is a grand Victorian-era building that serves as an emblem of the city’s rich history. Constructed in 1874, it was designed by the esteemed architect Alfred Norman. The Guildhall has a distinctive blend of Gothic and French Renaissance architectural styles, making it a sight to behold.

The building was severely damaged during the World War II bombings, but it was restored to its former glory in the post-war period. Today, it is a Grade II listed building and hosts a variety of events including concerts, exhibitions, and civic ceremonies. The Great Hall, with its imposing organ and fine acoustics, is particularly well known. The Guildhall is not just a building, but a symbol of Plymouth’s resilience and enduring spirit.

The Plymouth Plan

During my grandparents’ 1947 visit, the city was in the midst of rebuilding after the severe damage it endured during the Luftwaffe air raids.

Plymouth was one of the first British cities to undergo wide-scale reconstruction after World War II. This reconstruction resulted in a modern centre characterized by open spaces leading to the waterfront.

The city council had started planning for this reconstruction as early as 1941, with a plan completed by September 1943.

Bound in brown and green, and beautifully printed on cartridge and art paper, a handsome quarto volume illustrated by photographs drawings and maps presented a complete account of the intended reconstruction of the blitzed city and set out a bold design thought out in every detail. At least according to a 1944 editorial in Plymouth’s Evening News newspaper.

A mass of rubble where once stood a warren of buildings was to be replaced by several precincts, hotels, banks, the civic centre, a concert hall and an extensive shopping centre with a Great Way built right through the city centre to the Hoe. The Admiralty had purchased land for the extension of the Royal Dockyard, contributing to the city’s evolution.

Known as the ‘Plan for Plymouth’, after being approved by the council actual work began in 1947. The architect Patrick Abercrombie, one of the UK’s leading town planners at the time, played a critical role in these rebuilding efforts as did city engineer James Paton Watson.

The rebuilding was a vast undertaking, but Plymouth rose to the challenge, creating a new city from the ruins of war. The War Damage Act and its amendments offered compensation to property owners affected by war damage, facilitating the rebuilding process. The major part of the construction took four years with subsidiary work taking place until 1962.

As one of the first British cities to undertake wide-scale post-war rebuilding, Plymouth was moving towards a modernist future. Besides St. Andrew’s Church and the Guildhall, Royal Parade was restored. The new buildings in white Portland stone included Dingles department store. A high-rise Civic Centre also rose from the bomb damage.

The avant-garde plan led to a modernist pedestrianised city centre with sweeping open spaces leading to the waterfront and the Hoe. The legacy is still enjoyed by Plymothians today whose city enjoys nine miles of seafront and forms part of the SW Coast Path.

Patrick Abercrombie was knighted in 1945 for his services to town planning. His plans for London, Greater London, Hull and Bath came to fruition and he is credited with inspiring the New Towns movement.

In the modern-day Street View you can see tree-lined boulevards on the other side of which stands a row of slab-sided weathered concrete buildings beyond a six-lane carriageway. You can have a look around here.

© Google Street View 2023, Google.com

In the old photo, the building to the right of St Andrew’s Tower is the pitched-roofed Treasury. Next to that, two small towers depict the outline of a roofless, bomb-damaged Guildhall. Next comes a large tower above another roofless two-story building. This has not survived and presently allows for extra car parking for the Guildhall. In an old postcard, these are described as municipal buildings next to Basket Street which has also not survived.

Notice in the old photo the wall beside the pavement contains no mortar, the courses of brick are laid dry on top of each other.

Plymouth’s tramways

A view along Union Street, Plymouth,,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Also noticeable in the old postcards are tramlines on the roads. The tramways in Plymouth were originally four separate networks operated by three different companies, which were later merged under the Plymouth Corporation. The first company, Plymouth, Stonehouse, and Devonport Tramway was the first tramway in the UK built under the Tramways Act 1870 and was initially powered by horses before being converted to electric power.

The second company, Plymouth, Devonport and District Tramway, used steam and horse power before being electrified. The third company, Devonport and District Tramway was electrified from the beginning.

From 1872, the Plymouth, Stonehouse, and Devonport Tramway was operational, running from behind the Theatre Royal and up to Devonport.

Across the network, horse-drawn trams were eventually replaced by electric trams in 1907. However, due to bomb damage from World War II, the network was closed in 1945 with the redevelopment plan being built around wide roads for cars and busses.

Pearl Assurance House, Royal Parade, Plymouth,

Mutney – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

It’s up to the people of Plymouth to decide whether or not the redevelopment is a success. As an outsider looking in, it seems more brutalist than modern. The spaces are too wide, the layout is too regimented. Perhaps ironically, a shortage of steel and concrete meant that some cities on the Continent were more pleasingly rebuilt to their original layout using original materials. Plymothians feel free to contradict me!

© Always Worth Saying 2023