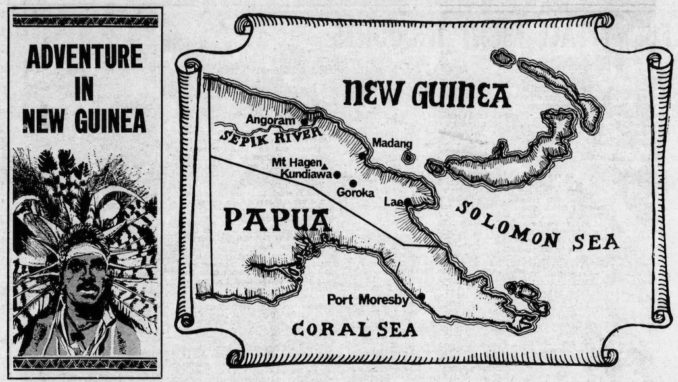

In 1969, my uncle, John Alldridge visited New Guinea to “observe the attempt to weld a primitive people to a modern society”. This is the fourth of his reports for the Vancouver Sun. – Jerry F

Adventure in New Guinea,

Vancouver Sun – © 2022 Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

We reached the village just before dark. It was two hours since we had left Angoram before we found the island in the reeds, where narrow canals break off from the river’s main stream.

I cut the outboard engine to quarter-speed and probed our way cautiously in the half-light up one of those tortuous canals, sounding for shoals every 50 yards.

The village is a large one. Fifty big grass-thatched houses lining both sides of the deep-water channel; each big enough to hold three families and built on stilts high above the water.

The people are desperately poor. So poor that most of the best young men have left to find work in the settlements down-river. For generations it has depended on the skill of its crocodile hunters, who feed the village with the crocodile meat and sell the skins down-river.

But crocodile hunting is a chancy business at best to men who rely on the harpoon spear because a shotgun — with ammunition at a shilling a cartridge — is out of reach.

So the village has frankly turned to prostitution. Not all those long canoes gliding furtively under the stilts at night are carrying fishermen.

I climbed the steep ladder of slippery bamboos into the rickety guest house above, and sat down in the darkness to eat my supper.

While I waited the village settled down for the night. In one hut a fire still flickered then went out. Somewhere a dog barked. A child cried. A man quarrelled furiously with his wife.

Presently the hunters climbed into the hut, sat down on the floor, lit their pipes and went into conference.

There would be no moon until late tonight. That was a good thing. But the river was running high. And that was not so good.

A crocodile hunter likes low water, where a crocodile can be cornered in the reeds and cannot swim away.

Then it was time and we went down to the canoes.

Three canoes were going out tonight. Two would sweep the eastern end of the lagoon. Tumban, Abkei and Kirrit would take Masta up the western end.

I never saw their faces. They would always remain in my mind as three black silhouettes cut out sharp against the night sky.

But Tumban, as the leader and harpooner, stood in the prow of the canoe. Abkei and Kirrit, in the stern, propelled and steered the canoe with long broad-bladed paddles.

The canoe was about 18 feet long and no wider than a racing skiff.

With the five of us there was barely six inches of freeboard. I wondered desperately where they would put the crocodile if they were lucky enough to catch one. And then what would happen to us?

They had rigged up a rough wooden stool amidships for Masta. I was to sit there for four hours: doubled up, scared to move for fear of overturning the canoe, until all feeling had left my legs.

So we slid over the mud and the pit-pit grass into the deep-water channel and glided into the blackness.

By day the Sepik is long — it meanders in great loops for 700 miles — and broad and monotonous. As tame as the Thames at Henley.

By night, in the dark, it is sinister and full of menace. The plop of a fish. The skutter of a duck among the reeds jolts your heart into your mouth.

With long, effortless strokes the paddles drove us away from the channel until now we were cutting through a water-meadow of giant lily-pads, which shivered in the whirlpools set up by the paddles.

At a signal from Tumban, in the prow, the paddles stopped. And we drifted, silent as a hollow log, midway between the two banks.

Never taking his eyes off the water Tumban reached behind him for the powerful long-handled torch and suddenly began sweeping the reeds on the nearer bank with a steady beam of light.

I reckoned we were now no nearer than 20 yards from the reeds; but these crocodile hunters have cats’ eyes in the dark.

Then, as suddenly, the light was snapped out. Once more we drifted in the darkness. So quiet and still it was that I dare not slap at the cloud of mosquitoes that settled on my face and arms.

An hour passed slowly like this; the light snapping on and off as regularly as a search-light probing every clump of reeds, every break in the tall pit-pit grass behind. Then, suddenly, the long beam focused on a single spot low down in the reeds. And stayed there.

“He’s seen one,” whispered Thomas, the interpreter, from behind us.

No need to tell me. I could feel the excitement run through the boat as it turned in to follow that steady line of light. In the prow Tumban had never moved. His left arm, fully extended, held the torch exactly at eye-level.

The distance narrowed, and then — still holding the submerged crocodile hypnotized in that unwinking eye of light — Tumban reached ever so slowly behind him and felt unerringly for the harpoon, six feet of bamboo topped with ten murderous prongs, lying ready at the bottom of the canoe.

I knew then we were going in for the kill. And I was as frightened as I have ever been.

A submerged crocodile offers the smallest game target in the world. Just two eyes — that glow like coals of fire in the torchlight — and the tip of his snout exposed above the water-line.

Tumban must hold that fascinated crocodile in the light just long enough to get into position and drive his harpoon deep down between the eyes.

There would be no second chance. An unwounded crocodile can crash-dive and vanish like a submarine. A wounded crocodile — and New Guinea “salties” run to 25 feet — can upset a canoe with a furious flick of his tail.

Slowly now — dead slowly — we glided into the reeds, following the light as if hauling on a rope.

For a moment I saw — or thought I saw — two points of fire burning in the darkness. Then Tumban’s spear came up and smashed down with the speed of light.

There was a tremendous convulsion in the waters, as if a depth-charge had suddenly blown up under our bows. The canoe rocked violently, and the light snapped out as Tumban struggled to keep his balance.

In those few seconds of eye-dazzling darkness I heard a noise as if a wet sack of

potatoes were being dragged through the reeds.

Then the light was stabbing out again. But it was too late now. The crocodile — wounded or not — had got away. I have never felt so relieved …

That was the last chance we had that night.

For another hour we patrolled that stretch of reeds, lying off in the darkness, listening. Then an enormous golden full moon rose up from behind the reeds and floodlit the river.

We turned the canoe and paddled away until we could smell the sour, sharp smell of the village again.

But they will be back tonight. And every night for the next week. For they know where he is. One night they will get him.

They can’t afford not to get him. An 18-foot “saltie” — and he is all of that — at the regulation price of 30s an inch (less 25 per cent to the buyer), means a fortune in wives and beer and fishing gear to the men of the river.

This is the way, then, they have hunted crocodiles on the Sepik for generations.

There are other ways, says Paul Rysavy, my Angoram host.

You can trap him on a long light-line with a hook baited with rotting meat. Flying-fox is best, but snake will do. The croc smells the meat, swallows it whole — crocodiles can’t chew — and takes the hook in his throat.

Or you can go after him with a shotgun. This is the quickest and safest way. But it can be a messy business. And a badly-aimed shot can ruin a valuable skin.

Having bagged your croc, you must have him skinned at once, then rubbed in salt and rolled before sending him down-river.

I have seen bundles of rolled crocodile skins in Paul Rysavy’s trade store on the river at Angoram. They look like so many monstrous Bismarck herrings.

From Paul they go on to Singapore and Hong Kong to be turned into handbags and shoes and brief-cases and belts and wallets. Some of them even find their way back to Paul’s trade store to be sold all over again.

Paul Rysavy practically runs Angoram. Besides acting as agent for three airlines and carrying on a flourishing business in native carvings and antiques, he manages the fascinating Angoram Hotel, which — like the rest of Angoram — is pure Somerset Maugham.

As Paul says, if you want to succeed in New Guinea you’ve got to be adaptable.

The Rysavys — Paul and his delightful wife Michelle — are Czech by birth. They got out of the homeland in 1948 and have been Australians for the past 14 years.

They have two sons away at school in Queensland and a seven-year-old daughter, Helen, a water-baby so much at home on the river the natives call her “Puk-Puk Marie” (Miss Crocodile).

Behind the hotel the blond-bearded Paul has a pool of baby crocodiles, all teeth and claws, and some of the most erotic, primitive carvings I have ever blushed to see.

Now I shall never see a pair of crocodile-skin shoes without thinking of the friendly, eccentric Rysavys. And that night on the Sepik.

Reproduced with permission

© 2023 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023