In May 1969 my uncle, John Alldridge, described the voyage of Allcock and Brown for the Montreal Star. This is the first of his reports. – Jerry F

John Alldridge recalls the epic flight of Alcock and Brown,

Montreal Star – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

MANCHESTER — She hangs now, like some huge box kite, suspended for ever between Col. S. F. Cody’s 1912 biplane and Messerschmitt’s first rocket-propelled ME Komet in the aeronautics gallery of the Science Museum.

A section of faded yellow fabric on her port side has been stripped away to reveal a fragile skeleton of wooden spars and criss-crossed wire.

From the catwalk above hangs a replica of her cockpit; no bigger than that of a sports car, with barely room for two men to sit squeezed in side by side.

The notice describing her reads: “Vickers Vimy, 1919”

Originally designed as a night bomber, she has a wing span of 67 feet, three inches, a fuel capacity of 865 gallons, and on that first trans-Atlantic flight carried a load of more than five tons.

She is powered by two water-cooled Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines of 316 horsepower, driving four-bladed wooden tractor propellers, which gave her a cruising speed of approximately 90 miles an hour.

But there is nothing to tell you of the two Manchester men who flew her, of the terrible storms they encountered in that open cockpit, of a cripple crawling out on both wings six times over the Atlantic to clear the frozen engines of ice and snow.

This is their story. And to find the beginning you must go back to an early morning in Manchester in April, 1910.

In a clover field at Fog Lane, Didsbury, a huge crowd had been waiting all night to watch the French airman Louis Paulhan touch down to win the Daily Mail prize of £10,000 for the first flight from London to Manchester.

Among the hundreds who surged forward to greet the Frenchman and shake his hand was a young engineering apprentice of 17, John Alcock.

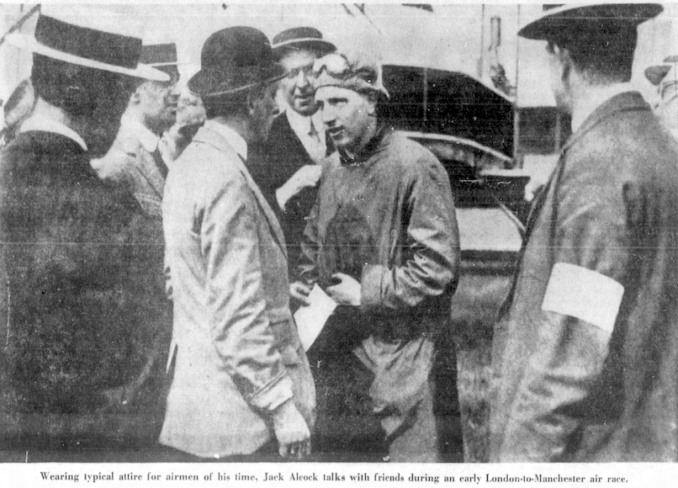

Wearing typical attire for airmen of his time, Jack Alcock,

Montreal Star – Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

Jack Alcock — he was always known as Jack — was born Nov. 5, 1892, in a Manchester suburb, Old Trafford. His father worked for Sir Edward Hulton’s Press, and Jack was the oldest son.

There was little in his boyhood to mark him as a future pioneer. He appears to have been a normal schoolboy but with a fascinated interest for anything mechanical.

He had a passion for making hot-air balloons from tissue paper and paste and sent them soaring upwards by the heat of methylated spirits soaked into wads of cotton wool.

Some of those balloons were 12 feet in diameter, and took him hours to make. From balloons he graduated naturally to box-kites, made of balsa wood and silk.

He left school at 16 in 1908 and went to work for the Empress Motor Works as an apprentice. This firm built and repaired motor cars and bicycles and Jack was soon completely at home in the workshop, tinkering with engines and transmission systems long after his working day finished.

His fellow apprentices remember Jack Alcock as a short, stocky young man with an engaging smile and a shock of ginger hair that was forever falling into his eyes.

He was a happy-go-lucky lad, game for anything. “Jack was always ready to have a go,” one of them recalls.

“I remember him once jumping into the seat of one of the firm’s lorries and driving it right through a brick wall. After that the manager, Charles Fletcher, forbade him ever to drive one of his vehicles again.”

He had few social graces. He took no interest in what he wore. And he was only really completely at ease when flying or talking flying “shop.”

“But he had an infectious good nature. Jack liked everyone and everyone liked Jack,” a friend has said of him.

It was while he was at Empress that he was put to work on his first aeroplane, a “flying machine” commissioned by a wealthy customer.

It was a handsome affair, all varnished mahogany and gleaming brass. But when it was tried out on Manchester Racecourse, apart from a few erratic hops, it failed to leave the ground.

In 1911 Alcock left Empress and went to work as a mechanic for Norman Crossland.

Alcock had met Crossland when he was building that ill-fated flying machine. Crossland was already an enthusiastic flyer. He had been a founder-member of the Manchester Aero Club, and a steward at the first air meeting ever held in Britain, at Blackpool in October, 1909.

Crossland took an instant liking to Jack Alcock. He taught him to drive and took him on cross-country reliability trials.

But Jack’s ambition was to fly.

His chance came in 1912 when his old firm, Empress, was asked to repair an aeroplane engine for the French aviator, Maurice Ducrocq.

Alcock, hearing about it, took time off from Crossland to work on it. Afterwards he was sent down to Brooklands, southwest of London, to install it, and Ducrocq was so pleased with the job that he took Jack on as his mechanic.

At Brooklands — then one of the two headquarters of British aviation (the other was at Hendon) — Jack Alcock was in his real element at last.

Besides assisting Ducrocq he worked with A. V. Roe, erecting aeroplanes and preparing them for test flights. He flew Farman biplanes and carried out exhaustive tests on the new Sunbeam aero-engines.

Best of all, he met and got to know personally the great ones of the air — men like T. O. M. Sopwith, Freddie Raynham, Gustav Hamel of France, and Harry Hawker, the daredevil Australian.

Thanks to Ducrocq, Alcock took his Royal Aero Club pilot’s licence before he was 20. Flying Ducrocq’s own Farman he proved a brilliant pilot, making his first solo after only two hours’ instruction.

And that was in 1912, when dual control was unknown and the pupil had to lean over the pilot’s shoulder to rest his hands on the joystick.

In the same year he took part in his first air race — London to Manchester. He finished fourth on the outward leg and second on the return.

Most of his spare time in those days was spent with his friends Raynham and Harry Hawker — thrilling the crowds that would gather for the frequent flying meetings at Hendon.

By 1914, when World War I broke out, Jack Alcock was one of the best-known pilots in Britain. He immediately joined the Royal Naval Air Service.

To his annoyance, the Admiralty found him too valuable for combat flying and put him to training other pilots instead. Many men who were to make a name for themselves in the air were to thank Jack Alcock for it.

One of his most famous pupils was Flt. Lt. Warneford who won the Victoria Cross for shooting down a Zeppelin over Ostend. Another was H. G. Brackley, later to become a rival in the race to fly the Atlantic.

But Flight Sub-Lt. Alcock was anxious for action. And in December, 1915, he got his chance. He was transferred to No. 2 wing of the RNAS on the island of Mudros, where in due course he enjoyed all the action he could wish for.

Here he had 12 months of operational flying in all types of aircraft, including the big Handley Page 0/400, which had been specially built to bomb Constantinople.

But his wings were clipped during a bombing raid over the city. He made a forced landing behind Turkish lines and he and his crew were taken prisoner.

Throughout the weary months of captivity Alcock kept thinking of a prize offered way back in 1913 by Lord Northcliffe’s Daily Mail — a prize of £10,000 for the first man to fly the Atlantic from any point in North America to any point in the British Isles within 72 continuous hours. The prize was as yet unclaimed.

If that flight was ever to be made, argued Alcock in his filthy prison camp, it would take a big, powerful plane to do it. A plane very like his own Handley Page 0/400.

NEXT: How Alcock met Brown

Reproduced with permission

© 2022 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023