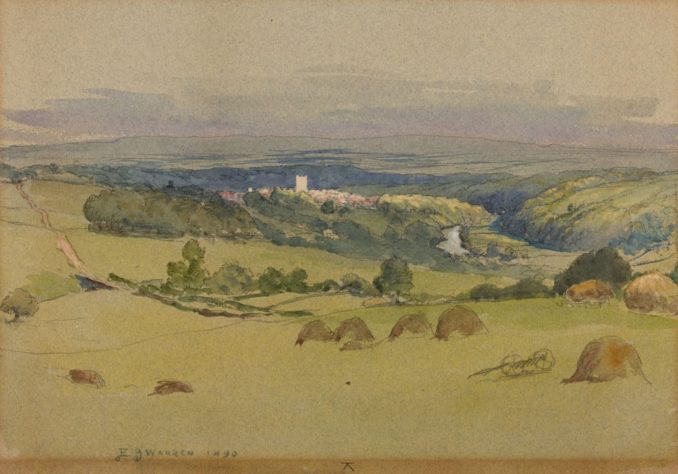

Harold Broadfield Warren, 1859–1934, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

We’ve forgotten something important

I’ve always been a bit of an oddball, so the following may reflect that. But it seems to me that the British people, and perhaps the people of the West in general, have forgotten something important. Even most denizens of this good website seem not to think about it much. I wonder if our forgetting of this thing, is the reason why we’ve allowed mass immigration into our country over the last 25 years, without much protest. Furthermore, I sometimes even wonder if this was part of a plan: we’ve been deliberately distracted away from thinking about this thing, and onto debating other questions, in order to circumvent the protest.

The thing that we seem to have forgotten is the value of our land area. Here I am using the possessive “our” in a specific way. I am not talking about individual ownership. People do seem to value land area that they individually own: that is shown by the fact that larger houses and larger gardens command higher prices. No, I am talking about the unoccupied land around us that we don’t individually own: the farmland, the countryside, the land that is currently being concreted over to build new housing estates and warehouses.

How can we use the possessive “our”, or talk about ownership, for such land? Because we have the legal right to live near this land (i.e., in this country), and we benefit from living near it; and because not everyone in the world has this right. Moreover, the benefit available from the land area is limited, so the more of us sharing this benefit (the more people with the legal right to live in the UK), the less benefit accrues to each of us. Here are some of the ways in which we benefit from this type of collective or “right of residence” ownership of land:

- The amount of land area per head of population determines how big our houses are, at a given price point. Basic economics – the law of supply and demand – dictates that the amount of available land determines the price for a given area. And in consequence of that, it determines how big houses are, and the rooms in those houses, for a given price. This is why Americans, at least in the less crowded states, have on average bigger houses, with bigger rooms. People certainly seem to value larger houses when they want to buy one, but they don’t seem to see the connection between the amount of land around them that they *don’t* personally own, and how much house they’re going to get for their money.

- The unoccupied land around us can be used for leisure. The British people pay hundreds of pounds to go on holiday to foreign countries where there are unspoilt views and great places to walk, but there doesn’t seem to be much protest when those things are removed from their immediate vicinity via the construction of housing estates, road junctions and warehouses. (There’s a lot of this going on around me at the moment, and no protests that I’ve seen.)

- The unoccupied land around us can be farmed on, providing a supply of food which, being near us, is both cheaper and more secure than food from further afield.

- Resources other than food come from land. Fossil fuels: coal, natural gas, oil. Renewables: wind and solar farms. Water: reservoirs. Like the land (and the food), we don’t individually own these resources, at least not to begin with. But they pass into the hands of local companies (or farmers) of whom we are the customers. The more customers that there are (people living on the land), the higher demand will be, and by the laws of supply and demand, the higher prices will be. Put another way, the more people there are, the smaller each person’s share of the resources is. The more we are impoverished.

Thus our right of residence does give us a type of ownership over the land of our country. In fact, I would suggest that the historical meaning of the word “country” is an “area of land owned (in this collective sense) by its residents, and defended against outsiders who might otherwise take some of that land area for their own benefit.” Note that this definition of country doesn’t refer to race or culture. It doesn’t need to: if the citizens of a country value their land, and seek (in the main) to pass it on to their own descendants, continuity of race and culture would largely, and automatically, follow from that.

Tribes used to fight each other, and countries used to go to war, over land. But now it seems that we just don’t care.

Distractions

What makes me think that we don’t value our land area? Partly it’s because I don’t see it mentioned much when immigration is discussed. But it’s also because I don’t see much protest against mass immigration, even though this means sharing our land area with more and more people. I don’t think it’s enough to say that “most polls show that the British people would prefer lower levels of immigration, therefore the politicians are to blame”. The Covid restrictions very quickly got 100,000s of people protesting along Oxford Street and in Parliament Square. Where are the protests against having our land area taken from us?

I can think of several reasons to explain why the British people might no longer value their land area, but they are all a variation on “out of sight, out of mind”. Two are due to technological advances. Firstly, we no longer work the land: thanks to mechanisation, only a minority do. Hence the cliche which states that many people think that “food comes from supermarkets”. Secondly, technology has provided screen-based forms of entertainment which don’t involve getting out into the countryside: TV, films, video games. If people spend all their time at home, in shopping centres or the pub, watching soap operas, Strictly or football, they don’t spend much time looking at the land around them; and what the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve over.

But I sometimes wonder if there’s another reason: has there been a deliberate attempt by some elements in government, reflected in the media, to distract us from the value of our land, and make us think that immigration is about a different question? That different question is: “what type of people are the immigrants?” From the onset of mass immigration in 1997, the subject was framed as one of race (if you don’t like immigration, you’re a racist), culture (are you for or against “multicultural Britain”?), politics (whether the “asylum seekers” are genuinely fleeing persecution or not), or economics (whether immigrants contribute taxes – “we need hard-working immigrants”). None of this is about our limited land area or having it taken from us. Have the British people been deliberately distracted from this?

Note that when immigrants work and pay taxes, this isn’t really compensating us for the land we’ve lost: the purpose of taxes is to pay for ongoing services such as roads, schools, hospitals and the various levels of government, including benefits and pensions. And when immigrants buy property, the money they pay for that property doesn’t really compensate us for the loss of the land area either. The sale price of a house or land doesn’t include the right to live here: that’s something that has already been given away to the immigrant who is looking to buy a house here, and as far as I can see we’re giving it away in large quantities, without demanding anything of similar value in return. That’s the priceless “good” that I’m talking about in this article.

Even on this good website, I don’t see many comments focusing on the value of our land area. Most comments about immigration are about what type of people the immigrants are, or about what they cost us in terms other than the loss of our land. I see comments about culture (questioning “diversity is our strength”) and race (are we are being “replaced”?). I see comments about illegal immigrants, and “gimmigrants” benefitting from free housing and handouts. I see comments about hotel bills, and the overall cost to taxpayers. All valid complaints and concerns, but rarely do I see comments about the loss of our priceless land area.

If, for example, we only ever complain about illegal immigration, we are not objecting to giving our land away to millions of Eastern Europeans, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians, three million Hong Kong Chinese, and who knows how many more Indians and Chinese with work visas, which will become right-of-residence. But, I hear you say, you quite like the Eastern Europeans, you know a few of them and they’re mostly good people? Or the Chinese, they’re hard working? Hmm, that kind of proves my point. You were easily distracted onto the question of “what type of people are they?”, and away from the value of our land area.

I also know Eastern Europeans, and Indians, and those I know are good people. But I am more disturbed when I hear people talking in Eastern European or Asian tongues, than I am when I hear people talking in, say, German, or in an American accent. It’s not that I prefer the company of Germans or Americans to Eastern Europeans or Indians. It’s because I think that migration between the UK on the one hand, and Germany or the USA on the other, is more likely to be balanced: as many going as coming. In other words, we’re taking as much of their land, as they’re taking of ours. That’s fair. Not so, at least not recently, with the Eastern Europeans and Asians.

I also don’t have a problem with secondary immigration, by which I mean that if we meet someone from another country, fall in love with them, and marry them, we should both have the right to live in this country. I suspect that we allow other types of family immigration at levels that we shouldn’t, and also that immigration by marriage is abused by many. So perhaps secondary immigration should be more restricted too. But the main point of this article is not to discuss what types of immigration should and shouldn’t be allowed. It’s about whether we value our land area, and whether we think about it when discussing immigration.

Arguments

For me, almost every other political issue is of lesser importance than the fact that we are giving our land area away. I want to say to people: “Tories vs. Labour? Why do you care about that, when you don’t care that we’re having our land area taken from us? To lefties: “low pay / fuel poverty / ‘social injustice’? Why do you care about those things, when you don’t care that we’re having our land area taken from us? Don’t you realise that will makes the poor even poorer?” To righties: “illegal immigration / culture / race? Why do you care about those things, when you don’t care about having our land area taken from us?” Or to put it another way, if we allow it to be taken from us, we can’t complain about who ends up with the stolen goods.

If you think I’m becoming a bore at this point, spare a thought for my family and friends. Whenever they express unhappiness about anything to which unbalanced immigration might have contributed, I can’t help but point out the connection. New housing estate being built on countryside near your house? “Do you ever speak out against mass immigration? If not, you’ve only got yourself to blame.” Stuck in traffic? I use the same response. Don’t like congestion charges? Ditto. Sometimes I get a response to the effect that they don’t see the connection. I don’t try to explain it, I just repeat: “if you don’t see the connection, you’ve only got yourself to blame.” (I’ve never been very socially popular. Did I mention that I’m a bit of an oddball?)

My way of thinking also provides a ready retort against ‘remainers’ who claim to have identified some economic ill-effect of Brexit: “What about the economic value of our land, which the EU was allowing unlimited millions to come and take from us? Did you ever think about that?”

I want to say a few more words about the other question that is often debated when talking about immigration: “what type of people are the immigrants?” In my opinion it’s harder to use this as an argument against mass immigration, and it’s also a weaker argument than pointing out the loss of our land area. It’s harder to use because it is easy for the listener to label you a racist or, if you’re talking about culture rather than race, an insular “little Englander”. It’s even harder to use if you’re actually talking to an immigrant, or if there is an immigrant in the group of people amongst whom you’re speaking – something which will become more and more common following recent levels of immigration.

And it’s a weak argument because, as we all know, and as the person you’ll be trying to convince knows (even if they’re British), a lot of immigrants are good people. If you use “some immigrants are bad people” as an argument against immigration, your listener might think “well, that’s not true of most immigrants, so I guess most immigration must be OK”.

On the other hand, if your argument is that our land area is being taken from us, and in unfair quantities because the immigration is unbalanced (i.e. predominantly in one direction), that’s a very simple statement about fairness, and not critical of the immigrants themselves. An immigrant to this country who now has right of residence should, in fact, share this sentiment: continued mass immigration will impoverish them and their descendants, just as it has impoverished us. (I daresay we are all better off than we were 25 years ago in terms other than “land area and resources per head of population”, but that would be due to advances in technology. Without those advances in technology, I suggest that we would be poorer in every sense.)

Where might we be?

Giuseppe Milo, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Where would we be if we hadn’t forgotten the value of our land area? When, in the first years of New Labour (after the floodgates had opened in 1997), our TV screens were full of talking heads telling us about multiculturalism, and “anyone can be British”, and “immigrants are hard-working and we need them to pay taxes”, perhaps we wouldn’t have obediently start arguing with each other over “what type of people are the immigrants”. Instead, perhaps our reaction would have been: “Hold on, that’s not the first question, is it?” Perhaps we would have realised that the first question is whether it’s OK for us to share our land area with more and more people; for us to have more of our countryside concreted over, or blighted by road noise; for our young people to be unable to afford housing; for our roads to be clogged; and for our beauty spots to become crowded instead of isolated, tranquil places. All without our gaining a balanced and compensatory amount of land in other countries. A critical mass of opinion might have been formed, leading to protests like those we saw against Covid policies. Perhaps the government might have had to back down, and concede to the principle of balanced migration on a country-by-country basis. (I realise that this is quite possibly just a fantasy…)

For those who have made it (almost) to the end of this missive, but who still think that the most important question is what type of people the immigrants are: I believe that balanced migration on a country-by-country basis would largely address that concern, too. Firstly, the numbers immigrating into this country would be much smaller; and secondly, they would be mainly from countries that other Brits (in similar numbers) wanted to move to (and were moving to). So the people from those countries probably couldn’t be that bad.

To sum up this article in a single sentence: the next time you are troubled by evidence of mass immigration, perhaps your first question shouldn’t be “What type of people are they?”, but rather, “Did we consent to have that land taken from us?”

© Fenman 2023