Somali national army soldiers,

AMISOM Public Information – Public domain CC BY-SA 2.0

Somalia’s recent history is also a tale of grave miscalculations made by foreigners in a very foreign land. Knowing nomads happily demonstrated their supremacy and disdain for outsiders, the so-called fruits of civilization were not seen as much by them.

Understanding the roots of violence in Somalia requires knowing the uncompromising nature of their environment. The harsh life of nomads revolved around survival. Camels and water were important tools, but so were good relations with other people and their clans. Kinship ties were paramount and were expected to be upheld in war and peace.

Every Somali child knows by heart his or her genealogy more than 20 generations, back to the revered common ancestral eponym of all Somalis, Somaale, from the words “go and milk”. Beyond this hero the line is traced presumptuously up to the Prophet Mohamed or to noble Arabian families. From Somaale, the lineages divide into six clan families. Political allegiances are determined by the male line, so Somalis don’t ask each other where they are from but whom they are from[1].

Clan has always been the last refuge, the last security during crisis, the only proven guarantor of safety when the world falls apart. “The rains can fail, wells can dry up, pastures can turn to dust,” states John Drysdale, a Briton who has fought alongside and lived among Somalis for decades. “It needs blinding faith and clan loyalty to keep everyone alive.”[2] “Somali society traditionally offered men a choice of two ideally contrasting, and mutually necessary roles: that of a warrior (waranle, literally ‘spear bearer’) or man of God (wadaad).”

Across the stark Somali land, there are always too few resources, and therefore too many reasons to fight. From ownership of camels and women to pride and cultural praise for a man engaged in killing, desert rivals rarely saw eye to eye. Camels were, and are, still revered in Somali history. It was the camel’s ability to sustain life, just as relief aid did during the early 1990s civil war – that made it worth fighting for. Exactly 100 camels were the blood money to be paid to atone for the killing of a Somali man – no other currency would do. In terms of camels, women are worth 50.

Among themselves they are divided only by clan, by relationships between extended families that stretch back over generations. Somalis were deprived of their natural ethnic homogeneity before the turn of the 19th Century, when their ‘nation’ was one of the many victims of the whimsical carve up of Africa by colonial powers at the Berlin Conference of 1884-85.

With divisions imposed from abroad the dismemberment of Greater Somalia served the ambitions of future leaders by providing a ready-made reason to war against neighbours. Differences among clans would in turn serve as reason to war against each other.

Spread across the Horn of Africa, ethnic Somalis were split five ways. The border with Ethiopia lopped off much of the Ogaden and Haud deserts to the West, Djibouti was excluded in the north west and given to the French; and the border with Kenya divided southern “Somalia”. Aspirations of one day uniting Greater Somalia, liberating those Somalis forced to live under foreign banners, were evident in the national flag unfurled at independence in 1960: five points of a white star on a blue background.

The greater Somalia dream was resurrected by Mohamed Siad Barre, the dictator who came to power in a military coup in 1969.

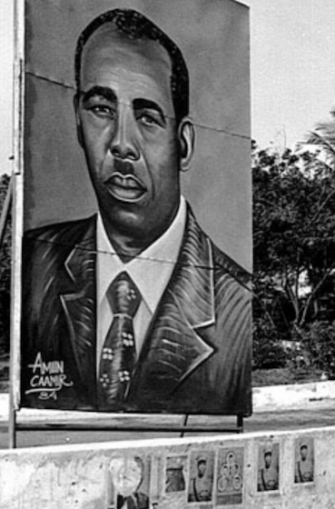

Poster in Mogadishu of Mahammad Siad Barre,

Hiram A. Ruiz – Public domain

He hid the mystery of his iron-fisted rule behind dark glasses. A tiny Hitlerian moustache adorned lips that gaped like those of a bottom-feeding fish which earnt Barre the derisive nickname among Somalis as ‘Big Mouth’.

Ruthless in every way, Barre maintained his stranglehold by tight control of the army and security services. And – through attacking the ‘cancer’ of tribalism in public, quietly played clans off one another. Probably nothing less could have kept Somalis at relative peace under a central authority.

Barre anticipated the coming chaos “Tribalism and Nationalism cannot go hand in hand,” he declared. “It is unfortunate that our nation is rather too clannish; if Somalis are to go to Hell, tribalism will be their vehicle to reach there.”[3]

Barre’s ideology was to destroy the clan system holding ceremonies to bury the grip of clans. No matter of the leaderships’ whims, ties of blood kinship were too embedded in the Somali psyche to be exorcised.

The abiding faith in clan, coupled with modern weapons amassed by Barre during the Cold War, led to disaster. Unimportant as Somalia’s natural resources are to the outside world – limitless sand, a few drops of low-grade oil – Somalia sits as a strategic gateway to the Middle East and Red Sea route to the Mediterranean Sea and Europe. Banking on this strategic fact, Barre was happy to ensure Somali figured in the Cold War Superpower calculations, first with the Soviets and later Americans. Somalia was the first sub-Saharan country to sign a friendship treaty with the Soviet Union and 6,000 Soviet soldiers and civilians ran Somalia as operating out of a “mini-Kremlin”.

They turned a rag-tag Somali army into a 25,000-man fighting force armed with heavy artillery, AK-47 assault rifles and MiG fighters. Schools with teachers taught more political theory than maths.

With Superpower rivalry high, the US in the early 1970s were allied to Ethiopia, the historical scourge of Somalia viz the Ogaden and Haud. American Peace Corps volunteers were stoned in the streets of Mogadishu and by 1971 they were forced to withdraw. US diplomats were spat on and by 1977 US Embassy staff was down to three. Mogadishu was plastered with posters that showed Somali peasants stomping on “Uncle Sam”. The Soviet weaponry value to Somalia totalled US$270 million.

In 1977 buoyed by military hardware and most likely notions of natural superiority, the Somali army marched into the Ogaden. Within two months, 90% of the Ogaden was in Somali hands, the partial dream of restoring Greater Somalia was being realized.

The Soviets, however, had already begun to support the young Ethiopian revolutionaries that deposed Emperor Haile Selassie. Their efforts to persuade Barre to form a Marxist alliance with Ethiopia failed, and Barre forced the Soviets to make a choice. Tired of Barre’s irascibility, the Soviets switched allegiances, prompting the remarkable Cold War flip-flop in the Horn of Africa. Overnight, Soviet advisors moved from Mogadishu to Addis Ababa and within months 15,000 Cuban troops, Soviet tanks and hardware worth US$1 billion, were deployed to “protect” Ethiopia’s borders. The Soviet realignment belatedly caused the American turnaround, as Barre played the Cold War card to find a new source of weapons. Jimmy Carter promised military aid but Congress insisted that Somalia first withdraw its troops from the Ogaden. Barre had miscalculated.

Ethiopia began to recapture the Ogaden. National pride was dealt a severe blow, a bad result for any Somali warrior for whom victory alone assures power and credibility.

Ethiopian National Defense Force Corporal,

Eric A. Clement – Public domain

Defeat was so total, Barre feared Ethiopian units would cross into Somalia. Arms were anxiously distributed to civilians and refugees from the North. Those weapons in public hands haunted Barre until his fall.

For a decade from 1978, despite Barre’s repressive measures, US threw US$800 million into Somalia, ¼ for military “aid”, in exchange for its own military access to ports and airports. Former colonial master Italy contributed US$1 billion from 1981-1990, more than half of which went on weapons. As unpopularity grew, despite his bottom lip service to ending clannism, Barre replaced top officials with his own clansmen. By 1987, half the senior officer corps were Marehan or related clans. Armed opposition groups emerged based on clan affiliation, and insurrection erupted in Hargeisa in the North. In 1988, Hargeisa was levelled in a fruitless attempt to rid the regime of an Isaaq clan-based rebel group.

Somalia Air Force jets took off from Hargeisa airport then promptly turned around to make repeated bombing runs on the city. This act finally ended US military support.

Anarchy reached its peak in 1991 when rebel groups began infiltrating Mogadishu and more weapons became available on the black market. Resultingly, even the 5,000 “Red Beret” presidential guard, all drawn from Barre’s Marehan clan abandoned him taking with them the collected loot from dozens of Embassies. They departed Mogadishu in a convoy stretching more than 10 miles in length, flanked by tanks and armoured vehicles.

Barre who’d vowed many times, “When I leave Somalia, I will leave behind buildings but no people,” stayed in Mogadishu. He didn’t have long to wait. An amphibious unit of US Marines from the USS Guam, diverted from final preparations for Op Desert Storm in the Gulf, evacuated 270 US Embassy staff in early January 1991. By 26 January, rebels had fought their way to Barre’s hilltop residence at Villa Somalia, forcing him to flee so abruptly in a tank, that sacks of money were left in the parking bay.

For reasons unclear, Barre’s decline seemed to have been deliberately ignored or more likely, misunderstood by the US Government. In 1990, Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf told Congress that military aid to the Barre regime was critical, “To help Somalia retain its political and territorial integrity.”

This was not the only misreading by US policymakers. Missing the clear signs of Barre’s fall, the US had built a UD$35 million embassy, complete with a 9-hole golf course. It opened on 4th July 1989. Officials later “conceded” the project may have given the “wrong impression”. The embassy was abandoned in January 1991 to eager hordes of looters. Armed guerrillas and civilians scaled the high walls with ladders; à la Saigon, with the Ambassador James K. Bishop forced to flee by helicopter under Operation Eastern Exit.

Aerial view of the front of the US Embassy Compound,

Perry Heimer – Public domain

Not far away from the Embassy another “ceremony” took place. A group of escaped convicts had burst open the tall wooden doors to loot the riches of the church. Beneath the sculpted Stations of the Cross, they laid down their guns to dig up the grave of the Italian bishop of Mogadishu, the first foreigner murdered in 1989 when Barre’s security services started losing control. With digging finished, they tossed aside the skull of the Bishop and pried the teeth out for their gold fillings.

Footnotes

1 Lewis A. A Pastoral Democracy p 128 and other notes

2 John Drysdale, Whatever Happened to Somalia? The Sunday Times (London), 30 August 1992, pp. 8-9

3 Quoted in Lewis, A Modern History of Somalia, p. 222

© AW Kamau 2023