Just as an 18th century Président may stalk provincial France looking for innocents to corrupt, so bots chew their way through blogs looking for relevant wares to advertise. We must proceed with caution. On these very Going-Postal pages I have been assailed by offers of collapsable Made in Poland bus shelters. One-to-one scale, not for my model railway. Goodness knows why. Likewise, shipping containers and agents offering to shift them from my humble Debatable Lands dwelling to Dakar. Perhaps I’ve been hacked?

Given that our companion piece Question Time Review’s co-efficient of the panellist’s published works is to compare them to Amazon sales of a particular book authored by a particular French Marquis (and given I was fool enough to promise a review), I must be aware of being overheard by a prowling bot. Dear Puffin if, between little boxes linking to superior works of political comment, there are offers for the likes of Preparation H, forgive me, I have failed miserably and been less oblique in the use of disguised metaphors (artfully employed) than the Marquis himself.

Portrait du Marquis De Sade,

Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo – Public domain

The Marquis de Sade was born Donatien Alphonse François de Sade on June 2nd 1740, the son of Jean Baptiste François Comte de Sade and Marie Eléonore de Maillé de Carman. From a wealthy but dysfunctional family, Donatien was schooled by the Jesuits and commissioned into the French army aged 15. He rose to be a Colonel of Dragoon and fought against ourselves in the Seven Years’ War. In peacetime, he married a rich magistrate’s daughter with whom he fathered two sons and a daughter.

In the French style, as the son of a comte, he became a marquis. Also in the French style, he led the scandalous life of the libertine, seeped in carnal infamy, the details of which bear no place in a family blog. Even in 18th century France, such a thing led to a succession of court cases and imprisonment.

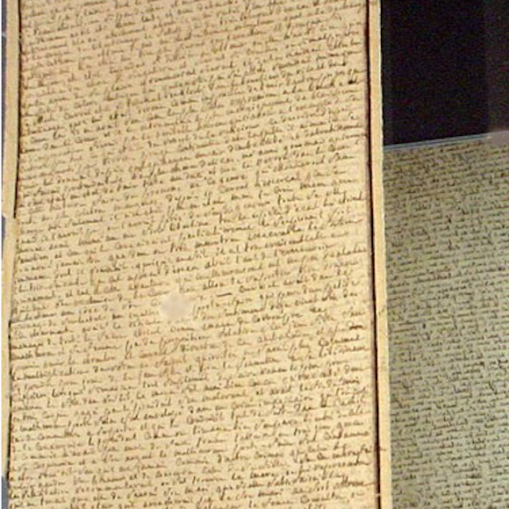

In 1785, De Sade wrote 120 Days of Sodom while imprisoned in the Bastille. Committed to a continuous 40-foot-long roll of paper concealed within a prison wall, it proved difficult to correct and edit and is therefore a rather rough work. When transferred to a lunatic asylum, De Sade’s manuscript remained in the notorious Parisian prison. Hours before the storming of the jail, during the French Revolution of 1789-1799, a certain M. Arnoux de Saint-Maximin was able to retrieve the manuscript for posterity.

In the wake of the upheaval, De Sade was released from captivity, re-named himself Citizen Sade and published his manuscripts. These included Justine and Juliette, the depravity of which resulted in his return to the asylum. He died there in 1814.

The Marquis Sade (1740-1814) in prison,

The Granger collection – Public domain

Storming of the Bastille,

Katefleurs – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

As for the surviving 120 Days manuscript, it was finally published in 1904 by Iwan Block under the pseudonym of Der Eugen Durhen. Viscount Charles de Noailles, whose wife Marie-Laure was a direct descendant of de Sade, bought the manuscript in 1929. His daughter, Natalie, inherited the script and kept it in a locked draw on the family estate while occasionally showing it to visitors. Passed to a friend, it was sold without her permission in 1982. There followed a near 40-year-long legal dispute culminating in the French Government purchasing the €4.55 million manuscript as a national treasure and depositing it in the National Library of France in 2021.

As for the published work, it can be downloaded for 50p and is too disgusting for words. The tale revolves around four libertines, led by a former judge called La Président, who lock themselves in a castle and listen to anecdotes related by fallen women, of a certain profession, while taking advantage of young victims lured there. Although I didn’t read it, the four libertines represent the four pillars of society; a duke, a bishop, a banker and a judge.

Having made an excuse and left part way through the written word, one falls upon reviewing the reviews of the theatre versions.

Ominously billed as ‘experimental drama’, The Stage reviewed a 1974 Roundhouse production. Critic M.A.M reported delivery consisted of full-voiced ranting from a cast wearing cassocks and knee stockings. Actors were propelled about the stage on trucks with character’s activities therefore removed from any ‘physical shape or gymnastic possibility’. Deprived of nuddies and groping, the reviewer decided the performance had little impact and was equivalent to an ‘average horror film’.

In 1991, Battersea Arts Centre presented a ‘grabby and flash’ but obviously derivative and superficial Nick Hedges production. Presented as a series of anecdotes, the play lacked atmosphere and suffered from an indifferent design placed in 1780s France. The Irish Independent were only able to mention, rather than to comment upon, Paulo Pasolini’s film version as it was banned in Ireland. Not a high bar, at the time The Independent pointed out that other banned films in the Emerald Isle included The Wild Bunch, MASH, The Graduate and Ryan’s Daughter.

There is a DVD version of the film. Confounded by a broken logistics chain, Brexit, fuel protests, rocketing transport costs, a railway strike and the war in Ukraine, it stubbornly remains partway between a lean-to-shed (retailing Gentlemen’s ephemera) near Antwerp Docks and Carlisle. I have wasted my €4.99 plus €2.50 for plain packaging. Fortunately, clips are to be found on a certain type of file-sharing website and a friend who understands such things was able to piece together a near-complete copy. Billed as a 1957 work, the cinematography doesn’t look like 1957 and it turns out to have been made in 1975. It is in Italian without subtitles and benefits from a soundtrack scored by the legendary Ennio Morricone.

Shakespeare wrote in short sentences containing short words, often monosyllables. Added to this, his characters talk slowly and one at a time. Italians, on the other hand, all talk at once and at great speed. They use their hands, arms and shoulders as much at their tongues and lips, and use long words (though not as long as the Germans) in long sentences (though not as long as the French). My Italian isn’t great. I cannot comment on the film’s dialogue as I couldn’t understand much of it, but the work is beautiful to look at.

Accidently happening across something sensible, this reviewer could understand the point that Pasolini was making. But he is wrong. We will come to that later.

Set in the Italy of 1944-45, under German occupation towards the end of the war, the action takes place in a lakeside villa of a senior local Fascist. Young innocents are rounded up and incarcerated. Mistresses tell stories while the young are humiliated. Not too young, De Sade’s early teens have thankfully morphed into Pasolini’s 30-year-old 1970s porn stars – think lead Sue Lyon in Kubrick’s Lolita.

Photographie de Pier Paolo Pasolini,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Although too cruel and too gross, the film is tasteless rather than depraved. Modern audiences will not be as shocked as they should be. The film is so old fashioned people even have pubic hair. The subsequent near half a century of ubiquitous normalizing pornography – not least from the internet – has dulled any outrage.

Likewise the humiliation. Although it goes too far, being forced to eat muck and being kept on all fours on a collar and chain, isn’t far south of modern-day mainstream reality TV staple. The mistake that Pasolini and De Sade make is to assume that human nature is corrupted by society and politics rather than by being flawed to begin with. Pasolini sees Fascism as a corruptor, De Sade the whole gamut of late 18th century French public life. The Marquis’s four pillars are the definitions of social construction; authority, ancestry, religion, and the necessity of capital.

The humiliation is also of private intimacy made public spectacle, shocking in its time but taken for granted in this social media age. Nudity and embraces are observed. De Sade and Pasolini’s honeymoon night following a mock wedding is not for the love of a couple but for the titillation of an audience.

An even more uncomforatble realisation than anything contained within a mucky scroll or old film, is that rather than being corrupted by social constructs, the present technology driven free-for-all shows human nature is corrupt to start with. Post-Enlightenment Utopian ideals, be they religious or political, can’t survive the inability of enforceable taboos to keep up with, and restrict, what people will do to each other if given free rein.

Detail of The 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinism,

Valueyou – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

© Always Worth Saying 2022