Malaga to Motril and Beyond

OSM Gibraltar,

OpenStreetMap.org and its contributors – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Having made an heroic 1952 journey from Carlisle to Gibraltar in a Ford 8 in order to visit Aunt Lil, Uncle Rob and cousin Anne, my father and grandparents set off for the return journey by a different route. The first photo on the trip is captioned ‘Coast Road Malaga to Motril’. In the background, we can see the double mountain that sits behind Málaga. A number of bays intervene before we reach the beach to the bottom of the photo and a tower at the top of the nearest small cliff jutting into the sea. Also jutting into the sea are three prominent rocks. You’d think this would be easy to find on Street View. Not so. Since the photo was taken a new highway has been built along the top of the cliffs and another along a seafront which has become heavily built up in the intervening seven decades.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

As for the tower, in a region previously home to Romans, Phoenicians, Moors and Carthaginians, there’s no shortage of such structures along the coast. Andalucia.com puts the total at over 100 with the most famous being the seven watch towers of Estepona. However, these tend to be circular with a domed top and a round hole halfway up the tower for ingress and egress via a rope ladder. Whereas the tower photographed looks slab-sided and with a flat roof.

Old guidebooks tell us that as we drive along the old coast road we’re making our way between the Arboran Sea and the Sierra Nevada mountains. The Nevadas contain the tallest mountain on mainland Spain, in fact on the whole of the Iberian peninsula, Mulhacén, which lies about 20 miles north of Motril and about halfway to Grenada. The peak reaches an altitude of 11,414ft.

The coast road is also known as the ‘Costa Tropical’ on account of the proliferation of tropical crops such as avocados and sugar cane in what today is an hour and a quarter drive along the A-7 (inland mega highway) or N-340 (coastal mega highway).

© Google Street View 2022, Google

Torre del Jaral might be a candidate then again it might not. The mind’s eye is tempted to the narrow old road across the narrow old viaduct beside the tower. The Gods of nostalgic travel should really allow for a Ford 8 to have squeezed past in 1952.

Nerja

Herading further east, the outline on the horizon to the top right of the next reproduction is distinctive and for our purposes matches the view looking up the valley from the main road towards Frigiliana. The photograph is captioned ‘Siera Tejbra and Almijara, Torrox’. The background is indeed the Siera Tejbra and Almijara, but we’re well beyond Torrox and approaching the environs of Nerja. Puffins will be pleased to hear that those prominent black dots about the fields aren’t ten-year-old girls with babies on their hips cleaning up spittal, but grazing fighting bulls.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Also in the 1950s, in the days when blacks and whites in their native United States couldn’t sit together on the bus or use the same restroom, American investigative reporters Herbert Sturz and Elizabeth Lytleton syndicated a travelogue of ‘horror facts smuggled out from Franco’s ‘police state’ ‘. How do you smuggle out a fact? Never mind. Over to Herb and Liz. They visited Nerja where they found girls of ten scrubbing out the filth and spittle of a Spanish bar for two shillings a week (10 pence).

The American reporters weren’t keen on marriage Spanish style which they claimed local women dreaded as it meant children and children meant even greater depths of poverty. The lot of the Spanish woman was even worse than in (trigger warning) “over-taxed Britain”. The two intrepid investigators invited their readers to picture the following flight path:

- As soon as she begins to walk, a little girl hugs a baby brother around on her hip.

- At seven she is deputy-mother to the household. She cooks, she shops, she washes clothes.

- At ten the next eldest sister takes over. The older girl goes out to work.

- At thirteen girls usually become nursemaids or general servants. The lucky ones get jobs in the fields.

And finally, when a girl falls in love she may have to wait from five to twenty years before she can afford to marry. Gracious. Mr Sturz and Ms Lyttleton had also visited Torre del Mar which regular readers will recall sat on the La Compañía Ferrocarriles Surbanos de Málaga railway line just before it struck inland towards Velez-Málaga. There they found a new housing project named after Generalissimo Franco which was insanitary and hopelessly inadequate.

The Tatler took a more optimistic view, albeit 4 years after our Nostalgia Album visit. Preferring hotels to housing projects, they reported upon agreeable Torremolinos pensions available for a guinea a day (£1.05). The resort was fast developing with, if you wanted to ‘escape your fellow countryman’, a necessity to head much further east, beyond Motril. Less well-known than the western end of the Costa del Sol, a ‘sub-tropical exoticism puts one in mind of the North Africa shore which it faces. The towns and villages retain the primitive aspect of Moorish days.’

Far from being an impoverished fascist pit, the Sierra Nevadas are an ‘unexpected mountain range with eternal snows lying 12,000 ft above the Mediterranean shores’. Later in the 1950s, Gordon Copper in The Sphere reported that Torremolinos was becoming a disappointing over-built resort. But he did find a Hotel Sexi at Almunecar west of Motril. Mr Cooper added that tourism was developing too fast with too many match-box hotels being ‘rushed up’. Much, much worse developments werew to follow further along the coast. Read on.

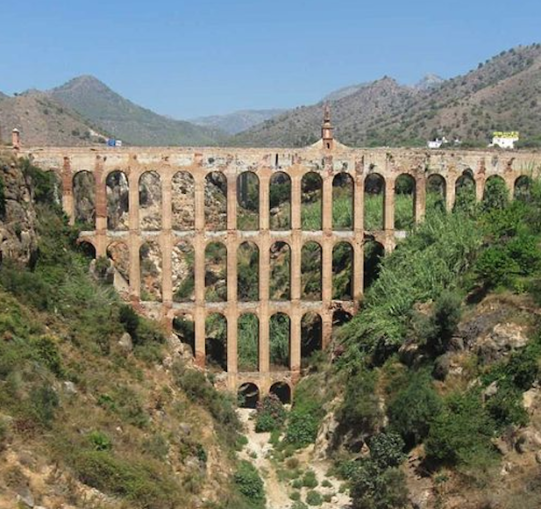

Eagle Aqueduct

After the Sierra Nevadas proper lie the Sierras de Tajeda, Almijara y Alhama that reach the sea at Nerja, 20km before Motril. Although the next photo is captioned ‘Aqueduct Torrox’. That’s not the case. The viaduct is the Eagle Aqueduct or El Acuaducto del Águila or the Puente del Águila which lies past Nerja (the eastern most resort of the Costa del Sol), not Torrox.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

© Google Street View 2022, Google

Acueducto del Aguila (Nerja),

Adán Fernández Berrocal – Licence GNU 1.2

The 120ft high crossing is the most famous design of architect Francisco Cantarero Martín. The construction was originally owned by the Azucarera-Alcoholera de San Joaquín factory company and was built to provide water to their sugar mills. In 1930 it was sold to the Azucarera Larios company, the vehicle of sugar refinery barons the Marquis of Larios and the Marquis of Paul. After falling into the ownership of Nerja City Council in 2005, the aqueduct was very nicely restored with the eagle weather vane that gives it its name impressively prominent in the centre.

Spanning the Barranco de Maro river, a road bridge nearby provides the exact view taken by my father all those years ago. Note the two-course stone block wall on top of the single-span arched bridge with the place the old photograph was taken now appropriately marked with a white stick. Unfortunately, the aqueduct has been photobombed by the N-7 viaduct which carries the Autovia del Mediterraneo to Almeria.

Heading Towards Almeria

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

To the east of the Sierra Navadas lie the Sierra De Los Filabres. Looking inland, we can see a castle to the far right and a flat area, possibly an estuary or river flood plain, to the left. There is a problem with identification in the modern day now that we are closing upon Almeria. For a distance of 30 miles along the coast, and up to 10 miles inland, all is covered in plastic. A sporadic outbreak had begun after Torre del Mar but by about 12 miles west of El Ejido the covering becomes solid, not breaking until about 4 miles east of El Ejido.

El Ejido aerial,

Kallerna – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

As a measure of the scale, El Ejido, pictured in the middle of the above photo, has a population of about 90,000. Beneath the sheeting, the greenhouses of Almeria province grow much of Europe’s fruit and vegetables, a large proportion of which is destined for supermarkets in Germany and Britain. About 3.5 million tons of crops are produced annually beneath 78,000 acres of plastic greenhouses.

If consumers think this is a price worth paying both for affordable fruit and veg and to improve living standards in a previously impoverished region of Spain, think again. According to DW.com, the workforce is provided by African immigrants seeing agriculture labouring as a gateway to residency in Europe. In 2018, 12,000 immigrants arrived illegally at the coast in 400 boats. Of the 100,000-plus local workforce, 30% are thought to be illegal immigrants. These workers have no contracts or social security and are poorly paid. Many live in improvised camps or ‘chabolas’. Meanwhile, the farmers who hire them can’t make a living either and complain of being undercut by produce from Morocco and Turkey.

Almeria

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

The town that gives the province its name lies to the east of El Ejido and outside of the worst of the sea of plastic. With a present-day population of nearly 200,000, Almeria was founded by Arabs in 955 AD with the Arabic name of Madīnat al-Mariyya, meaning “city of the watchtower”. A medievel fortress sits behind the town and in front of the town lies its port which was shelled by the German Navy during the Spanish Civil War. In the modern day, ferries cross the Med from here to the likes of Algeria’s Oran and a Spanish enclave in Morocco called mMlilla.

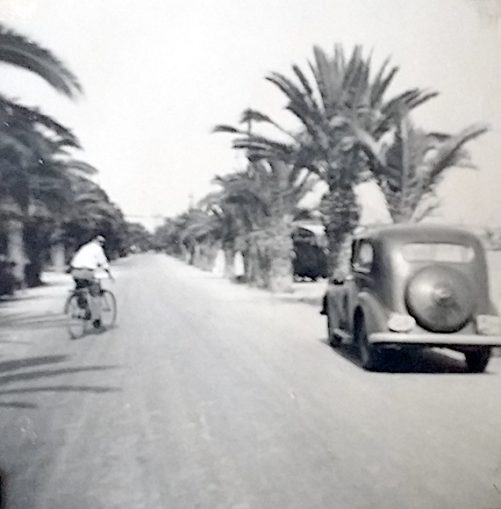

Presumably the photo was taken on the city’s old promenade which also formed the old coastal road, now known as the N340-a. A reasonable guess would place it here.To the left is the Parque de Nicolas Salmeron and beside that a row of mainly disappointing modern match-box buildings with only one or two reminders of what my father and grandparents will have driven past in the 1950s. All well and good, but where is the Ford 8 going next? Find out next time in Nostalgia Album!

© Always Worth Saying 2022