November 16th, 1809 (November 4th O.S).

This morning a gorgeously attired equerry from the palace cantered up to our tumbledown shack on a shining black horse to deliver a wafer of thick cream-coloured pasteboard with gilt edges. It bore a message, fortunately in French as our Russian is not yet what it might be. We are commanded to attend His Imperial Majesty forthwith. Emperors do not invite, or suggest that it might be convenient to attend. And no answer is required, save that of humble compliance.

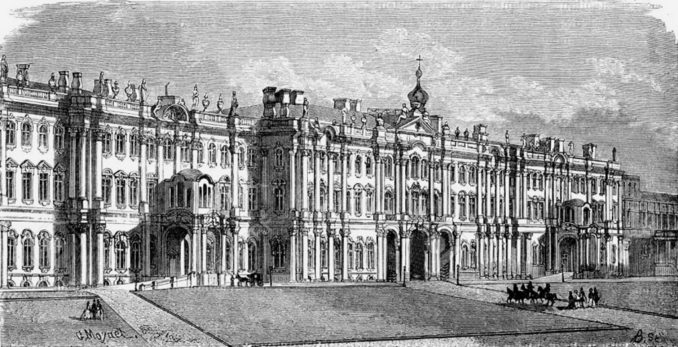

We packed our meagre effects, and off we trooped to the Winter Palace. It is an imposing building, not lofty – just three storeys high – but its front, bedecked with statues and urns, is so long that it stretches into the distance. We were directed to a lowly side entrance, where we were greeted by a gentleman who introduced himself as Grigory Putin, the Imperial Director of Music. From his demeanour, we infer that he directs much more than music, and in this uncertain place we are anxious to be on his side.

Today is Thursday, and we are to perform before the Emperor on Saturday – scant time for rehearsal, but after our travels we are accustomed to readying a show in haste to suit the circumstances. It transpires that the court orchestra has parts for La Vestale, brought directly from Paris, and we have agreed that its closing ballet shall be the main event in our performance. It will be preceded by a series of English, Spanish and Portuguese dances interspersed with acrobatic intermezzi performed with our talented troupe, and followed by a gopak to round off the evening with a fitting tribute to our Russian hosts.

Having left England in haste we have no suitable costumes, but with a wave of his hand Putin summoned a throng of imperial seamstresses, and they are stitching away as I write. Jem is deep in consultation with the orchestra, and Fred, ever practical, is arranging the rigging for Peter and Emily’s slack rope performance, and ensuring that no readily combustible draperies will hang too close to Bruin’s fire-eating act. I do not think that the imperial theatre will ever have witnessed anything like the fare that we plan to give them.

November 18th, 1809 (November 6th O.S.).

I write this after our performance – and what a performance! It was a triumph compared to which our show at Carlton House before the Prince of Wales was a mere fairground turn. The bears, gorgeously bedecked, danced and balanced and ate fire with a verve and dash that had the audience on their feet cheering louder and louder after every episode. Little Hugh’s performance on the Unirota, which he rode up and down the aisle while juggling with five jewelled eggs borrowed from the treasury, had them gasping. After the final gopak, dukes and duchesses besieged the stage to garland us with flowers.

When the applause had subsided, everyone trooped off to a reception in the state rooms of the palace. They are of unexampled magnificence, putting the motley residences of the English court to shame.

The courtiers were dripping with diamonds and rubies which, I am informed, can be picked up at the roadside in Siberia (though privately I suspect that the gathering is done by an army of serfs while an overseer stands over them with a great knout, a scourge with metal weights on each tongue). The courtiers are also drenched in perfume and, looking at it from the human point of view, they need it. To a bear’s more sensitive nose, the principal scent is that of unwashed humanity, overlaid with a discordant welter of musk and castor, ambergris and spikenard, and attar of roses and other floral extracts.

The palace itself, for all its glitter, is far from clean and all kinds of filth can be found in the corners. This, perhaps, is the essence of the Russian court: a shining facade of Frenchified elegance over a rough base reeking of the shaggy folk from the steppes. We bears can well understand this, as we too are superimposing our courtly dances on our natural behaviour – though we do it with greater grace and certainly greater cleanliness.

As I was musing on these matters, a splendidly attired nobleman approached Fred with a cry of ‘Knock knock, me ole cock sparrer! I ’eard as ’ow some English coves ’ad turned up ’ere wiv bears an’ all. An’ wot brings yer to ’Oly Russia, ’f I m’y be so bold as ter arst?’ He introduced himself as Count Bagarov, but we were all gasping at his mode of speech. Fred and Jem have the accents of ordinary Londoners, but he sounded as if he had been born in a thieves’ den near the docks.

Fred managed to say, ‘’Onoured to meet yer, Yer Serenity.’ (I blessed my foresight in teaching him the modes of address for the various ranks of the Russian aristocracy.) ‘We came ’ere in a bit of an ’urry, I ’as to confess. Things was gettin’ a bit borin’ like at ’ome.’ (By which he meant ‘dangerous’.)

‘Ow, yer runnin’, eh? Wot yer bin done fer?’

Fred explained with as much dignity as he could summon that he had been falsely accused of murder and condemned to death, but had been rescued at the last minute by his loyal companions.

‘So yer was sprung jest afore yer was ter dangle, eh? Yer got some fly foxes wiv yer, an’ no mistake.’

I will give the rest of this conversation in oratio obliqua, as it is becoming wearisome to transcribe their peculiar mode of speech. Yet let us heed the proverb cited by Apostolius, Ἀγροίκου μὴ καταφρόνει ῥήτορος, Despise not a rustic speaker.

Fred congratulated the Count on his fluent command of English, and the Count explained that he had been brought up by an English nursemaid born in Bow, who had come to St Petersburg with some London merchants to care for an infant who had perished of the measles, after which she had summarily been cast adrift. The old Count had rescued her and charged her with the rearing of his little son, which she had done admirably and, in her old age, was still residing at their residence in Archangel on the shores of the White Sea.

The Count now disclosed that he had approached Fred for a purpose. The family had acquired a polar bear cub whose mother had been shot by hunters, and had determined to bring him up as a pet. (At this, all the bears pricked up their ears to hear the rest of the story. None of us has ever seen one of these famous white bears, and indeed some dismiss them as mythical creatures.) All went well for a while, the Count said, but the bear, whose name is Nikita, is now almost fully grown and is chafing in confinement. He cannot be returned to the polar waste as, without experience, he would soon perish; but he is ill suited to be treated like a lapdog in the house of a nobleman. He has become moody and occasionally violent, and nearly killed one of his devoted keepers.

Would we, the Count asked, come to Archangel with him before the approaching winter made the roads impassable, and see what we could do to relieve Nikita’s sad plight? Fred glanced around at a circle of bears and humans nodding in assent. Not only are we coming to the aid of a fellow bear, we are securing ourselves a comfortable home for the northern winter, a season whose rigours drive even the hardiest bears to hibernate in a snowy shelter. As Horace wrote, Bruma recurrit iners, the sluggish winter returns.

At this point our conversation was interrupted by an equerry with a message from the Tsar himself. His Imperial Majesty commanded us to attend him on Monday morning, in two days’ time. Of course we had no idea of the purpose of this summons, but Fred had the presence of mind to explain to the functionary that our command of French was less than perfect – which was all too obvious – and to ask if Count Bagarov could be summoned to act as an interpreter where needed, something that our new friend was happy to do, understandably wishing to be seen as useful to his sovereign.

November 19th, 1809 (November 7th O.S.).

We have spent Sunday at the palace in grand style, accommodated, bears and humans alike, in splendid apartments with lackeys at our beck and call. Accustomed to instant obedience, they did not bat an eyelid when Fred asked them to bring forty pounds of raw meat for our sustenance. It was horse, and none the worse for that.

We attended divine service in the palace chapel. The structure is spacious and sumptuously decorated with shining golden mosaics, and the vocal music was of strange and wondrous beauty, but the order of service was most unexpected. The congregation takes no part in the proceedings, remaining standing and wandering around the edges of the chapel, while the worship is conducted by clerics in a high-walled pen in the middle, almost screened from view, though at one point the Host is raised to cries of acclamation. The rite is in the old Church Slavonic language, absolutely incomprehensible to all present. I prefer our English Matins, where one feels that one has some part in the proceedings.

November 20th, 1809 (November 8th O.S.).

This morning we had an audience with the Tsar. We had no idea of why he wanted to speak with us, except perhaps to examine a curiosity that had arrived in his land; but we soon found out.

There were fourteen of us: the ten bears, Fred, Jem, Dolores and Count Bagarov. We were ushered into the imperial presence and bowed in what we hoped was an acceptable manner. Dolores managed a tidy curtsey, which she had spent some time practising the previous evening.

The Tsar motioned us to a large table, where he sat on one side and the other humans took chairs on the other, while the bears sat on the floor in decorous and attentive attitudes. The conversation was conducted in French, with occasional assistance from the Count when Fred could not find the right word – but I will not tire you with details, and will simply report the bare bones of the matter.

The Tsar first addressed Fred: ‘I have heard that you fought the French in Spain and Portugal.’

Fred indicated that this was true.

‘Would you then give me your opinion of the French as a fighting force?’

Fred replied, ‘Sire, we were up against Soult, and he is a fine general and nearly had us more than once. But two things saved us. First, we were fighting with the population, and he was fighting against them, and so we were able to raise a local band of irregulars who harassed his troops quite effectively, with our aid if I may say so.’ He waved his arm to encompass our band of fighting bears, who had indeed dismantled many a French soldier. ‘And second, we have a general who can beat Soult at his own game, by which I mean Sir Arthur Wellesley. I believe that, in the long run of this conflict, Wellesley will out-general Soult and Ney and anyone that Napoleon can find to oppose him.’

The Tsar then turned to me. ‘Daisy, I have heard that you are a bear well read in the classical historians, and I would like to hear your views of this conflict.’

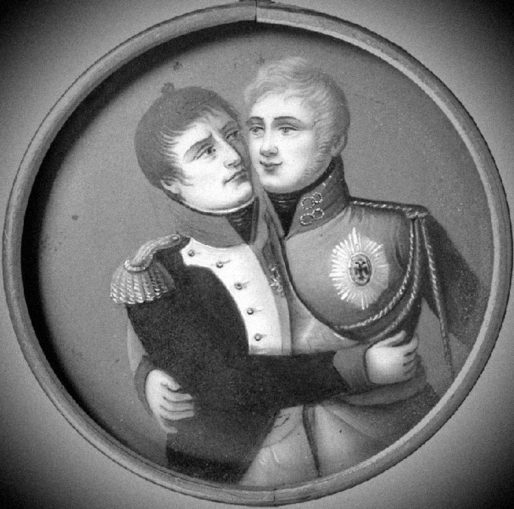

I took up my slate and wrote in French, Sire, I have indeed studied the works of Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Julius Caesar, Agricola, Suetonius and later authors such as Ammianus Marcellinus. But, if I may venture to make an enquiry that may be indiscreet, I believe that at present you have a formal alliance with Napoleon under the Treaty of Tilsit, and that my humble but honestly expressed views may not be favourable to that agreement.

The Tsar replied, ‘That, my dear bear, is exactly why I wished to canvass your opinion. Please speak freely.’

I wrote, Then, Sire, I have this to say. I do not believe that any alliance with Napoleon is to be depended on. Napoleon has one aim, and that aim is conquest. He desires Spain, the German and Italian states, the Low Countries, Poland and Britain as part of his empire, and I think that before long he will tear up the treaty and turn his envious eyes on Russia. And when he does, it will be his undoing. I hesitate to invoke your namesake, Alexander of Macedon …

‘No, no, go on,’ said Alexander of Russia.

… but he will make the same mistake. It is one thing to command an all-conquering army, and another to hold the lands that the army has conquered. I believe that if Alexander had not died suddenly in Babylon, he would have seen his conquests vanish in his lifetime. He went too far; they could not be sustained. I believe that Napoleon, in his mad dream of ruling the world, will invade your country with a huge army under able generals, and perhaps will penetrate it for many hundreds of miles. But the farther he goes, the longer and more vulnerable his lines of supply will be. He will be defeated by two things: the ever lengthening distance between his forces and home, and another force against which there can be no winning …

‘And what is that?’

… the Russian winter. It is something of which he has no knowledge, and for which he is completely unprepared. With General Winter on your side, you are assured of victory.

‘Daisy,’ replied the Tsar, ‘your wise words have given me much to ponder. I thank you, and I thank Fred, for your counsel. I hear that you are to spend our mighty Russian winter with the good Count Bagaraov, and if I need further advice I shall summon you again to St Petersburg. For now, you are dismissed, and I wish you a pleasant sojourn in Archangel.’

We all bowed and backed reverently out of the imperial presence, trying not to knock over the furniture.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player