Public Domain

I had probably already heard of the Zanzibar Revolution, perhaps I had read that Freddy Mercury arrived in the United Kingdom as a result of his family having fled the violence that took place there in 1964, before I had seen those disturbing images in the documentary Africa Addio which etched the event into my mind forever. Aerial footage captured by the Italian film makers shows hundreds of Arabs in their white gowns being led single file through palm groves seemingly resigned to whatever fate had in store for them, this is followed by scenes of mass graves waiting to be filled in. Armed guards overlook a frightened, huddled mass of the elderly, women and children sitting in what appears to be a cemetery with later footage showing these same people sprawled lifeless on the dirt floor. Hundreds flee in terror into the sea carrying their belongings above their heads in a panicked effort to escape the massacre in small boats. The filmers return the following day to a tragic, pitiful scene as the beach is littered with the corpses of those who could not make their escape, most of them apparently given it was low tide. Why are these events not given more prominence, and how had I not heard of the mysterious central figure in this tale.

The Zanzibar Archipelago and its Bhantu inhabitants had long been under the influence of Arab traders who were attracted to its strategic position off the coast of East Africa as a staging point for expeditions into deepest Africa. The Arabs introduced Islam to the local population and their influence in terms of architecture, language and culture dominate to this day. After a period of control by the Portuguese Zanzibar was ruled by the Sultanate of Oman who established a ruling Arab elite overseeing a thriving economy in ivory, cloves and most importantly slaves. It then came within the British sphere of influence and the practice of slavery was stopped with Zanzibar becoming a British protectorate in 1890 and thereafter considered part of the British Empire.

The population of the islands was highly stratified with 50,000 Arabs controlling the lion’s share of the land and wealth, 20,000 Asians dominating the middle class as artisans and businessmen and 250,000 Africans largely employed as manual labourers, domestic servants and in subsistence farming. Great resentment existed on the part of the African majority who were denied opportunities reserved for Arabs and Asians, they felt ill-treated, lacked representation and the country’s slave trading past was still within living memory. These factors were simmering just below the surface when elections were held in the spirit of the decolonisation process sweeping Africa with the Arab dominated Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP) defeating the African Afro-Shirazi (ASP) and socialist Umma parties in what was widely considered to be a fraudulent and gerrymandered charade. Civil disorder broke out over an illegitimate, Arab dominated government pursuing a future of closer ties with the Arab world rather than Zanzibar’s more immediate African neighbours. Nevertheless with the elections concluded independence from Britain was secured.

The new government proceeded to further inflame tensions by cutting spending in African areas in response to an economic downturn and making inflammatory comments about the perceived inferiority of Africans. They then, seemingly oblivious to their precarious position, dismissed all the African policemen thereby creating an ideal revolutionary vanguard of trained, disaffected, young men with intimate knowledge of the inner workings of the police force.

Weeks after the election the revolution began with a surprise night attack as around 40 men armed with spears and knives overran a police-station in the capital, Stonetown, manned by hastily trained new Arab recruits. The armoury fell shortly thereafter giving the revolutionaries access to ample firearms and before long the remainder of the main island’s strategic buildings were under revolutionary control and the fate of Zanzibar was all but sealed. That morning a man with a foreign accent referring to himself as the “Field Marshall” made a radio broadcast announcing the revolution to Zanzibarians and encouraged Africans to take to the streets and violently overthrow the Arabs. With Stonetown now secured the fighting spread to the countryside as rural Arabs put up a defence of their villages in what was to be a futile stand against the now heavily armed Africans and no doubt the precursor to events described in my opening paragraph. As Westerners evacuated they witnessed gruesome and widespread scenes of execution and gang-rape taking place openly in the streets of Stonetown and after two days of violence the estimated number of deaths is between 2,000 and 20,000.

In the following days, the Sultan having fled and ultimately taking refuge in Britain, life in Zanzibar began to return to something approaching normality in the aftermath of a frenzy of killing and looting. The Revolutionary Council was put in place comprising of leaders of the Umma and ASP parties with the ZNP banned and its leader imprisoned, ending the era of Arab domination.

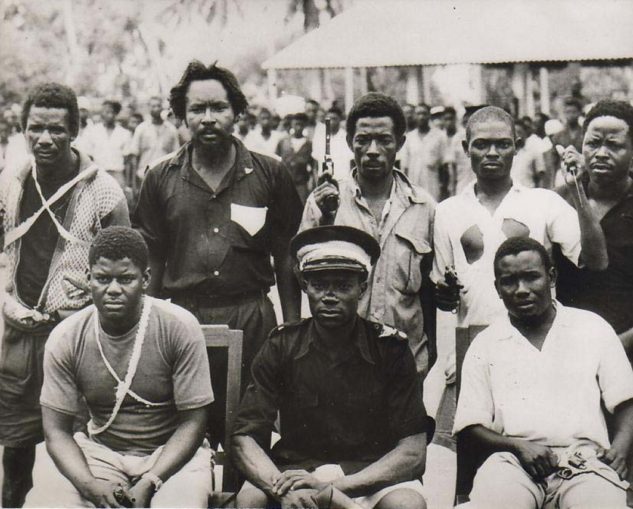

With the events of the revolution summarised I now turn my attention to the enigmatic Field Marshall. The revolution appears to have been planned and led by a charismatic young Ugandan migrant worker by the name of John Okello whose role is strangely downplayed in the official narrative. The new government quickly distanced themselves from Okello and on returning from a trip to Tanganyika he was denied re-entry and deported, never to return to Zanzibar. There are two competing versions of what transpired. The official story is that Okello, a relatively unknown union organiser, was selected as the man to front the revolution by the ASP leadership in exile due to his foreign accent in a ploy to give the impression the revolution had mainland support. For the more conspiratorial among you, the ASP was preparing a revolution with Cuban support while Okello, unaware of this and frustrated by the perceived inaction of opposition leaders, took matters into his own hands with no outside assistance. Either way, it appears that on executing the coup so effectively he was ousted in a power-struggle for which he was neither experienced nor politically savvy enough to compete in. I imagine the robust treatment of Arabs which took place under Okello’s watch may have been a great source of embarrassment to the new government too.

Okello returned to his nation of birth at some point where he disappears from the historical record (rumoured to have been murdered by Idi Amin who felt threatened by Okello’s celebrity status) and little is known about his activities post-revolution outside of poorly written African Nationalist fan fiction.

There are inevitable questions around the feasibility of a migrant labourer with no combat experience having engineered such a victory. On being asked where he gained his military experience by the British press Okello amusingly responded that he was “trained by the God of Africans” without the slightest hint he may not believe this himself. Almost all of what is known about Okello prior to the revolution appears to come from his own account.

Okello’s book depicts an early childhood in a small central Ugandan village tending the family goats. Following the death of both his parents at age ten he was sent to live with an uncle who doesn’t show much interest in raising the boy or his siblings. He abandons school and sets off to find his fortune, travelling from town to town across British East Africa going into excruciating detail on various menial and semi-skilled jobs he performs. He describes the mistreatment of African workers by their Asian masters and what he perceives as intense European hatred of Africans. He remarks to a friend that all the wealth is in foreign hands when it should be in the hands of Africans. He is involved in union organising and mentions in passing having interactions with the anti-imperialist movement. His writing is interspersed with Old Testament verses, prophetic dreams and frequent petitions to God revealing an intense religiosity.

The young African’s search for work opportunities eventually brings him to Zanzibar with he and a companion travelling there by boat under the cover of night. Within a short space of time of arriving and securing work as a stone mason he involves himself in local union organising and politics having taken the plight of Zanzibar’s Africans to heart. It is revealed that Okello himself approached the African policemen and planted the seeds of revolt having become frustrated with the pace of political change but realised that there was little point in beginning an uprising before the British had left. He again demonstrates a preoccupation with detail by explaining every minutiae of the planning and preparation in which, by his account, he is the central figure. In keeping with the religious theme of the book he provides his fighters with something resembling the Ten Commandments covering such topics such as personal hygiene, diet, moral instruction and complex (sometimes contradictory) rules on who can and cannot be killed or raped. Following the results of the election the die is cast.

Regarding the events of the revolution itself Okello again portrays himself in the commanding role exhibiting exceptional leadership and organisational skills along with extraordinary displays of bravery. It is Okello who leads the charge against the Stonetown police station and is responsible for the first fatality of the revolution, bayoneting an Arab policemen to death with his own rifle having wrestled it from him. In another scene he challenges an Arab villager who has been accused of killing innocent Africans to a machete duel in which Okello is of course triumphant. On the matter of the slaughter of Arabs Okello is somewhat regretful, but explains that “the bitterness of years of oppression inevitably produced many actions of vengeance”. The spontaneity suggested in his explanation seems at odds which what appears in the footage to be a premeditated and organised genocide (in my opinion).

Okello explains that he was not interested in power or politics, perceiving himself as a military leader (a Field Marshall no less) whose sole motivation was to free Zanzibar’s Africans and quickly transfer power to a civilian government. He speaks of tensions arising almost immediately over a Christian holding such a high profile position in what was an Islamic nation. The bitterness over his treatment is palpable, he is very obviously frustrated and offended at being pushed aside rather than shown the respect and adulation he deserves. He is scathing of a newspaper article which reduces his role to mere radio propagandist and claims the title of Field Marshal was a vain invention of Okello’s. At this point it is clear the purpose of the book is to get Okello’s side of the story across, to salvage something of a legacy for himself.

The book ends with Okello in a Congolese prison cell having been arrested (reasons unclear) travelling through that country with the intention of reaching Angola and taking part in the independence struggle against the Portuguese. He sees the ultimate prize as the liberation of apartheid South Africa’s black population. Throughout the latter part of his book he is utterly bewildered by his treatment and why he is not welcomed as a hero wherever he goes.

Was John Okello a minor player suffering from delusions of grandeur or the determined African nationalist, inspired by God, who by sheer force of will liberated the Africans of Zanzibar? I shall leave it to the reader to decide.

Sources: trust me bro.

© Zombie_Ramboz 2022