A promise was made to Puffins regarding a dispatch from Kazakhstan to report upon the fighting between Kazakh forces, Russian paratroopers and ‘fuel protestors’. Located at Bishkek in Kyrgyzstan, a correspondent was only 12 miles from the border.

Unfortunately, confusion rained at the bus station. As mentioned last time, although local writing is in Cyrillic, reading isn’t. Kyrgyz words, not Russian, appear in the ‘Russian’ script. To increase the chaos, observed printed scratchings suggest the co-existence of a Kyrgyz Latin script. Added to which a suspicion arises timetables are read up the way instead of down the way, long distances and slow roads making it difficult to tell what direction the times are going in.

In the same way a wise celibate priest has no knowledge of married life but observes, likewise an earnest reporter who is crap at languages listens to the Kyrgyz and devours anything pinned to a notice board. As in my own Debatable Lands, the natives do without aitches. They do retain a ‘sh’ sound as in the second city Osh (which is important to our tale), via a character in their own Latinised alphabet, ‘Şc’, or Ш in Cyrillic.

Rosetta Stone style, the table for a Wednesday’s Only stopping service to Balykchy (onboard refreshment trolley from Tokmok), is also presented in Arabic suggesting Şc can be improvised to چش. Then again it might not be. To be blunt, dear Puffin, the writing is so unfamiliar, an uninitiated foreigner might be spotted by a puzzled Kyrgyz trying to read the pattern of a bus station’s waiting room wallpaper.

None of this helps when scheduling an underling to Kazakhstan.

Suffice it to say, the wrong wobbly tin steps were mounted and, instead of hurtling to a war zone, armed with notebook and pen, to stand between Russian paratroopers and rioters, the Al-Archa Gorge was traversed. Rather than waste a trip, a day’s skiing was indulged at Ak Tash. War is hell.

Al-Archa is an alpine national park. More than 20 glaciers are nearby and several of the surrounding peaks reach over 12,000ft in height. As well as abundant trout, wild goats and roe deer, above the 7,500ft mark, snow leopards are said to hunt. After a hard day on the pistes, a yurt beckoned.

Being partway there, it would be a shame not to explore Kyrgyzstan’s second city of Osh. Halfway along the old Silk Road (to which it owes its existence), Osh is 187 miles south-east of Bishkek as the TezJet BAE 146 flys, or as a ten-hour road journey winding 377 miles through the mountains. In this case, overnight which detracted from the views. Incidentally, getting closer to China too which is only 80 miles east of Osh as the ak shumkar (white falcon) flies.

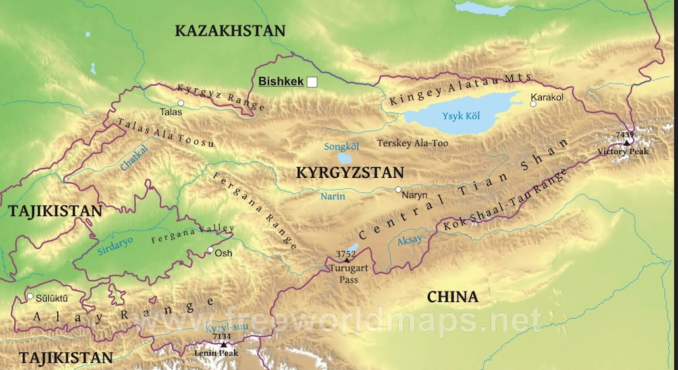

Kyrgyzstan via Free World Maps,

Courtesy of Free World Maps – Free World Maps

The above Free World Map is free for a reason. Not least of which, the uppermost ‘Tajikistan’ should read ‘Uzbekistan’.

Thought to be the oldest city in the country, having been inhabited for 3,000 years, the population of Osh is evenly split between Kyrgyzs and Uzbeks with a small number of Russians and Tajiks bringing the total to 300,000. The city centre is only about 3 miles from Uzbekistan. The frontier is marked with a combination of earth mounds and fencing, some of it through the outer suburbs. Ethnic hostilities can flare. ‘Many dozens’ were killed here in June 2010.

As for the weather, in January the temperature averages a bracing – 4C through the day with the mercury dipping to -8C by night.

As proof that inflation is out of control, a shared room is £4 a night, 25% more expensive than last week in Bishkek. But one does have one’s own washing machine beside the bed. However, the other residents seem to think they can use it too, resulting in endless journal jangling interruptions.

To the north of the city, the Sulayman Mountain appears abruptly from the plain of the Fergana river. Sheer rock faces rise a further 300 ft in height from a valley floor that is already at an elevation of 3,000 ft. Osh is at the eastern extremity of this valley with the lion’s share of Fergana belonging to Uzbekistan.

Sulayman is a sacred place, named after Solomon, the king and prophet of the Bible and Koran. A note on the religious experience of Central Asia. Islam expanded eastwards under the Umayyad Caliphate of 661 to 750 AD, between only 30 and 120 years after the time of Mohammed.

As ever, the new religion was superimposed over the old. Parts of the pre-existing protrude. For example, a holy mountain not all of whose claims are strictly Koranic. Sliding across the rocks aids fertility. Cave water dripped into the eyes cures poor sight. Entering another cave remedies baldness. The weightier guide books call this ‘cultism’, a welcome relief from the fundamentalism found in other parts of the Muslim world.

This is not happenstance. Until recently these peoples were nomadic. The faith hasn’t been passed down via a priestly elite but by an oral tradition within family groups, allowing latitude for local custom.

Whereas the Solomon of the Hebrew Old Testament was confined to 12 tribes and the holy soil of Israel, the religion of peace knows no bounds and, if Solomon was the greatest and wisest of kings, to the faithful there’s no reason why he couldn’t be buried in Osh.

No archaeological evidence exists of this, as no archaeological evidence of the existence of Soloman exists anywhere else.

Having noted that, we shall begin our ascent of this UNESCO world heritage site. Firstly, we pass a mosque. Notice the shell-shaped structure to the far side of the minaret to the right. This is a Soviet-era museum and viewing platform.

Continuing the ascent, we are now looking down on the mosque and over the city to the snow-capped Alay Range of the Tian Shen mountains. On the other side of which, about 50 miles to the south, lies the valley of the Kyzyl-suu which is bounded on its southern side by Tajikistan.

Regarding the mosque’s mountainside cemetery. I’ll bet a tiny ak shumkar emblazoned brass tyiyn coin to a green and gold 5000 Com banknote, before the days of Islam the same patch of land was used for sky burials where the dead were laid out as carrion for those sacred birds still commemorated on the coinage.

At the top of the eastern end of the saddle-backed mountain sits the Dom Babura mosque. According to Lonely Planet,

The one-room Dom Babura is a 1989 reconstruction of an historic prayer-room whose tradition dates back to 1497. In that year the 14-year-old Zahiruddin Babur of Fergana built himself a little prayer-retreat here. Later famed as progenitor of the Mogul Dynasty, Babur’s place of private worship became highly revered but various incarnations have been destroyed notably by earthquake (1853) and, in the 1960s, by mysterious explosion. Many locals are convinced that the latter was a Soviet attempt to halt ‘superstition’, ie Islamic pilgrimage.

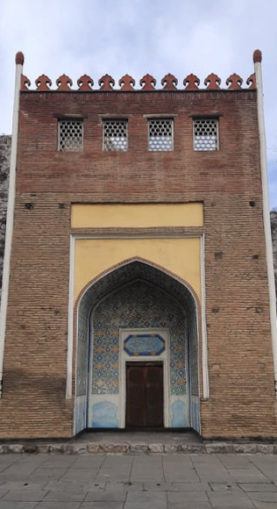

Back on the flat, and tucked behind the National Historical and Archaeological Museum, an interesting building (above) catches our eye. This is the mausoleum of Solomon’s vizier, Asaf ibn Burhiy who, in an instant, magicked the Queen of Sheba’s throne from Sheba to Soloman’s side ready for the Queen of Sheba’s arrival. As with Solomon, there is no evidence beyond the scriptural of ibn Burhiy’s existence.

As such, both himself and a mausoleum for him are ‘occultist’ or ‘ruhaniyya’ meaning they belong to the supernatural and lie outside the scope of religion and science. Such things puddle our modern Western minds but make more sense up a holy mountain, in the freezing cold, four thousand five hundred miles from home after a sleepless night beside an overworked washing machine. Living on a thousand calories a day in CCCP bars also brings one closer to the mystical.

A gentle stroll down Lenin Avenue, via school Number 17 Gagarin, takes us past the Dramatic Theatre and the football ground to the White House. The seat of local government, a giant statue of Lenin stands opposite. This nostalgia for Communism is summarised by French travel photographer Elliott Verdier thus,

“The USSR was powerful and Kyrgyzstan was part of this power.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the established markets for Kyrgyz goods disappeared. That bus to Balykchy now terminates in a former industrial city fallen into disuse.

Not quite the bubble or the swamp, Osh’s local government district includes plenty of small comradely bungalows of wood and corrugated metal but to the east, across the rather modest Ak-Buura River, posher concrete homes enjoy luxuries such as kerbs and drains accompanied by a welcome dearth of potholes.

As ever, some comrades are more equal than others.

Further Reading

Anika Burgess, Life in Kyrgyzstan, 26 Years After the Collapse of the Soviet Union

© Text and photographs unless otherwise stated Always Worth Saying 2022

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player