As usual, I start by thanking readers for their comments on the previous article.

I was glad 1642again picked up my implied thanks to the gods for living during a period when there was sufficient political freedom to enjoy the sort of adventures I was allowed to have. The bureaucracy of immigration, customs, environmental and other controls when moving from one country to another seemed irksome at the time but movement for ordinary people and not just the elite was at least still possible.

Glad too that Foxoles enjoyed my philosophical consolations and SharpieType301 giggled at my little joke and again posted the pic that gave rise to it. I also hope the advertisement on Endeavour’s web-page didn’t blind him and thought he was lucky since my own screen these days seems to be overwhelmed with a Plague of Pizza Ovens – I must install an ad-blocker. Commervanman thought he might make time over Christms to write an article telling us about how a Typhoon tossed about his large and strong steel ketch in Hong Kong and included a photo of it stranded there.

I would have liked to post here images of those comments and the pics therein to make them available to those who don’t have time or patience to look through all the “Comments No One Reads”. I sent several suggestions to SB on how to do that whilst still complying with his © policy. None were acceptable and I now understand you must have a © attribution with every image in a main article even if the same picture has previously appeared in a comment. So, if you’ld like to see the fun ones posted by Sharpie and Endeavour you’ll have to trawl through the comments until you find them and Commervanman will have to include a © attribution if he manages to write an article and includes in it the photo of his ketch parked on the rainforest floor, after self-identifying as a Landrover as Gotham suggested, or failing to change down to second on a sharp corner as ArthurDent thought likely.

I was very pleased so many liked my own photos in part 28 and that Whistler 80 thought you were all on the same journey with me. That is exactly how I hoped you would feel and share with me the joys and disappointments, the sense of failure and accomplishment, the trepidations and optimism of this new phase of my life.

Cynic asked an interesting question in this comment –

Ancient Mariner. Thank you for the stories of your travels. Did you ever find that people who sailed without modern aids were much more sensitive to the subtleties of weather and currents, able to detect signs of land while very far away, or had that already disappeared even in the Pacific?

I think most people in developed western countries have lost any such ability and rely almost exclusively upon modern aids. Some have a better understanding than others of the physics of natural systems, mostly acquired through experience rather than academic knowledge. A few, amongst those who have spent a lot of time at sea, do have a fair sensitivity, mostly amongst those fewer still who sail non-competitively rather than racing or those in motorised craft . I like to think I was approaching membership of that group towards the end of my sailing career but still made a mistake by heading for land when I’d have been better off staying far out to sea.

I don’t think any Western people are so attuned to the behaviour of the air, water, skies and wildlife around them as the Polynesian Navigators were around 1000 AD. Many local people in the Pacific and elsewhere still are superb sailors but not in the same way because they no longer attempt long oceanic voyages in canoes (except for one or two historical reconstruction expeditions).

Western sailors like Vasco da Gama, Cook, Bligh and their contemporaries were also master seamen as were some individuals like Joshua Slocum and a few in the twentieth century. But during the last 150 years or so, ancient skills, equipment and technologies managed by human brains, memories and muscles have been mostly replaced with modern materials, internal combustion engines, satellites and digital devices controlled by computers. Human operators are still needed in some cases of course but more to provide input data to their electronics than as observers and analysts of what is going on around them.

Similar changes have been taking place on the social level too. People I met in all parts of the world who have been exposed to Middle-Eastern and Western cultures were often much more mercenary than I imagine their predecessors were, especially in tourist countries like those in the Eastern Caribbean. The worst of that I ever experienced was on the Caribbean shore of Panama north of the canal. I met some Young American Volunteers in the US Peace Corps who told me they were teaching the locals “Tourism” as well as English.

“Ah”, I replied, “That will be why I had to pay a fee to moor my dinghy and pay at a gate to walk onto the beach”.

In more remote regions like the polynesian islands of the Pacific the same sort of attitudes exist in popular places like Papeete on Tahiti, Bora Bora, Nadi and Lautoka in Fiji. But the Pacific is so large there are still several much more remote places where the local people – mostly descendants of those ancient navigators – remain friendlier and more willing to share knowledge and resources with strangers, especially ones like myself who got there by their own efforts.

I don’t want to say much about my times in the Pacific in this post but I’ll illustrate those general remarks with one particular story from the Cook Islands, discovered and occupied by the Polynesians about 800AD sailing from their central base on Raiatea in what is now called French Polynesia.

A YARN ABOUT ALCHEMI IN THE PACIFIC

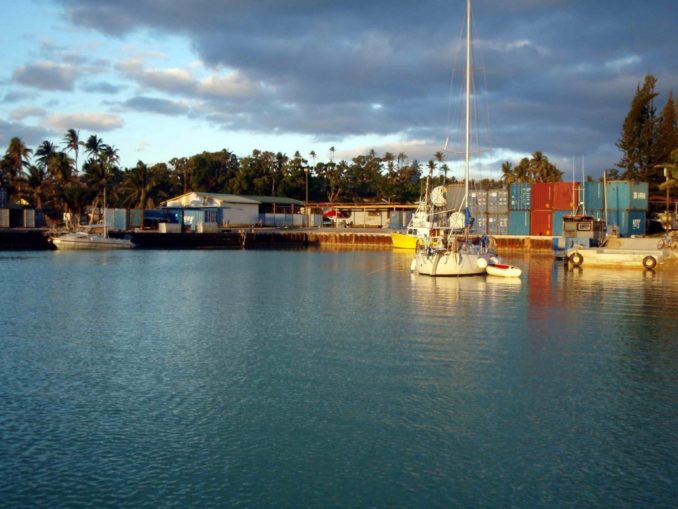

Alchemi arrived in Aitutaki during her second Pacific Crossing in 2010. It is a very low-lying coral atoll grown as most are on the crater rim of an extinct volcano that in this case has a wide and very shallow plateau of coral all around it.

A narrow channel about 2 metres deep has been blasted through the coral to the small harbour at Arutanga but parts of it silt up very quickly. The plateau ends abruptly at the outer edge with the rocky and steep seabed getting very deep very quickly as one would expect on the side of an extinct volcano. It is also in the Cyclone Belt and has been devastated on more than one occasion. It too is a tourist destination but still with some islanders who retain old values and customs.

I was pretty apprehensive about visiting at all but took the risk of anchoring outside the first night hoping like crazy the anchor wouldn’t get trapped in the rocks and have to be abandoned in the morning. That didn’t happen and I was able to time passage up the channel at high tide in daylight.

Alchemi still touched sand on the way in but her solid lead keel and strong construction coped with that and her engine was powerful enough to drive her off again and on into the harbour. Several weeks later though I was worried about getting out again fearing the yacht might touch again with bow or stern held fast in sand and the other end getting blown round onto the coral plateau. That fate was avoided by arranging to be towed out by the sports-fishing boat seen tied up to the wharf on the left hand side of this photo.

Another yacht was hanging off the wharf in the one available spot and I couldn’t tie up anywhere else on the wharf that had to be left free for other users. I secured Alchemi in a small pool just outside by tying her bow to two palm trees about 100 feet apart from one another and laying a stern anchor.

One of the first needs after clearing-in with Immigration and Customs was to get some local currency so I visited the bank in Arutanga and was served by Steph (from memory I think she had a Lancashire accent). We got chatting and she told me she was married to an Islander named Turua and ended up by inviting me to dinner with them at their home.

Having ‘phone access to the external world again I called my daughter in Australia only to have the ‘phone answered by a stranger who passed me over to my eldest granddaughter there, aged 10, who said – “Mummy is in hospital, can you come and help?”. Of course, I said yes, but that meant I needed to improve Alchemi’s anchorage somehow for three or four weeks and fly to Australia via Rarotonga and Auckland.

An additional anchor from midships was the best I could do physically but Steph and Turua were wonderful. They agreed to keep an eye out for Alchemi whilst I was away, invited me to stay in their home on the nights of my departure and return, and took/collected me to and from the airport. I thanked them by taking back from Australia Green Tea they couldn’t get on the island and shards of coloured glass from broken church windows – Steph needed it to make jewellery for tourists. I also bought two ukeleles from Turua to give as presents to my grandchildren.

Prompted to remember these events by Cynic’s question I was pleased to see from this page on the internet that Steph and Turua were still going strong in 2015 and hope that is still the case. Here’s a link to the sort of music the ukeleles can produce when played by an expert. The islanders have some good drummers too. Alchemi was still there when I returned, a little nearer the coral as the midships anchor had dragged a bit, but still undamaged.

Now, I must make progress with the early stages of my story and first long voyage.

A BIOGRAPHICAL DIGRESSION

One of my grandchildren and K2fd…. have asked for another climbing story even if its just small-time biography, so here goes. Perhaps it may also be of some interest to any Social Historians amongst you.

I first became interested in mountains when very young because my parents had themselves been young during the First World War. Working class families still had difficulty in feeding clothing and housing themselves at that time because they weren’t allowed to send their children out to work until they reached the age of 12, as required by the 1899 Education Act.

In a great leap forward after the war the 1919 Education Act raised the school leaving age to 14 and that turned out to be of considerable benefit to me through my father having to stay at school for 2 years longer than expected. That imbued him with a thirst for knowledge and a faith in the value of education that was a later benefit to him and even more so to me.

He did leave school then and became an apprentice in the GPO for whom he worked for most of his adult life. He also realised his prospects depended on improving his knowledge and skills and attended Night School until he was 25 years old, winning by those efforts a number of City and Guilds certificates. That helped him gain promotions and, at the end of his career, he transferred to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and was posted overseas to help a couple of colonies in Africa prepare their telecommunications systems and people for their forthcoming independence.

My mother didn’t have the same self-imposed drive for education and went to work after leaving school, also by co-incidence with the GPO, but in her case behind a counter dealing with the same sort of services offered by the Post Office today.

There was no TV in those days of course and the latest technology was radio, brought to the populace by the BBC founded in 1922 – one of my father’s hobbies was to build his own “Cat’s Whisker” set to receive their broadcasts. But telegrams had replaced semaphores in the previous century so my mother learned the Morse Code and became a proficient operator -.– .- .–. –..– / – .- .–. .–. .. -. –. / .- .– .- -.–. I do hope my internet translator got that right by the way, if only to convince you that your predecessors were just as smart as you are.

There was very little time and money for leisure activities in the late 1920’s and 1930’s for people such as my parents so they had to find their own amusements and pursuits. Both my father and mother had done that independently by taking up cycling and joining the CTC (Cycle Touring Club). That’s how they met one another. In due course, that led on to both cycle-camping and membership of the YHA (Youth Hostels Association) as soon as it was formed.

Unsurprisingly, I was brought up in the same way – I still remember my mother’s pride when my father and I (at the age of 12) were presented with “100 in 8” certificates one after the other at the Bristol CTC’s Annual Awards Dinner in 1948. The certificates signified Marshalls along a designated route had confirmed we rode 100 miles in 8 hours.

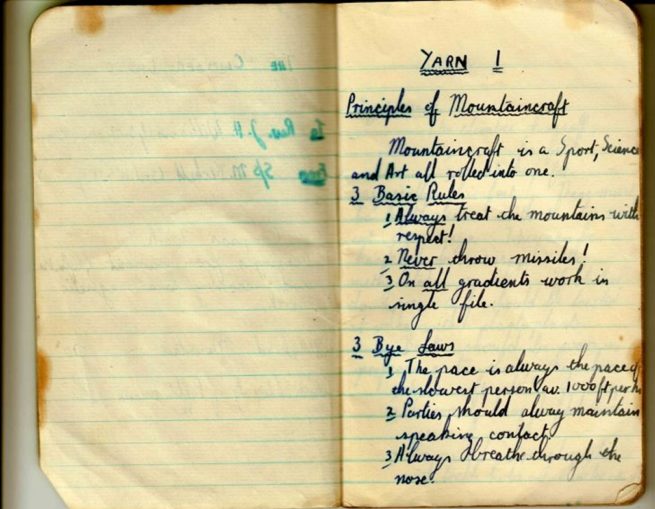

Leisure time in my teenage years was thus occupied with outdoor pursuits that included being a Boy Scout. In 1951 when I was 15, I read in “The Scout” magazine an advertisement for a Permanent Camp in Llanberis run by the Rector of the church there who had formed a Snowdon Troop. Scouts who were already members of a Home Troop could join that one as well. Whilst staying there the rector would give talks on Mountaineering and organise expeditions to peaks in Snowdonia led by experienced Senior Scouts that anyone with the necessary interest and stamina could join.

That seemed a good idea to me so I strapped my sleeping bag and army-surplus bivouac tent on the back of my bike and rode up to Llanberis, staying at Youth Hostels on the way. The quickest and pleasantest route was to cross the estuary on the ferry between Aust and Beachley near Chepstow and then ride up the Wye Valley. Here’s a pic of the ferry taken 8 years later in 1960, still 6 years before the Severn Bridge was built.

I thus became a member of the Y Wyddfa scout troop and began an interest in climbing that stayed with me in adult life. (The rector is not to be confused with his successor who had a fondness for young boys that did them no good at all.)

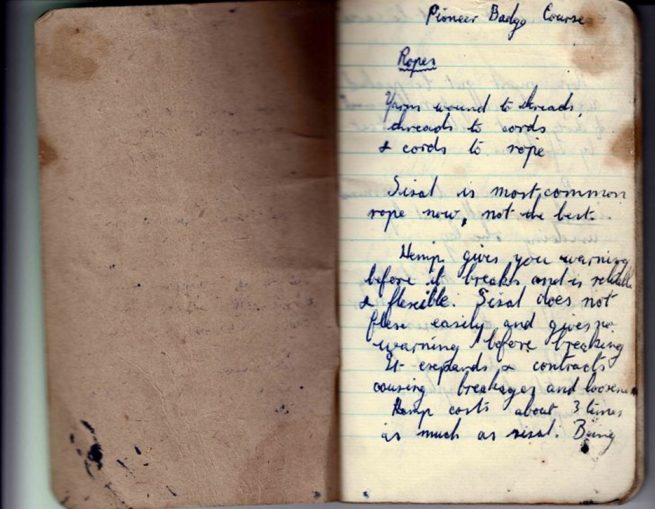

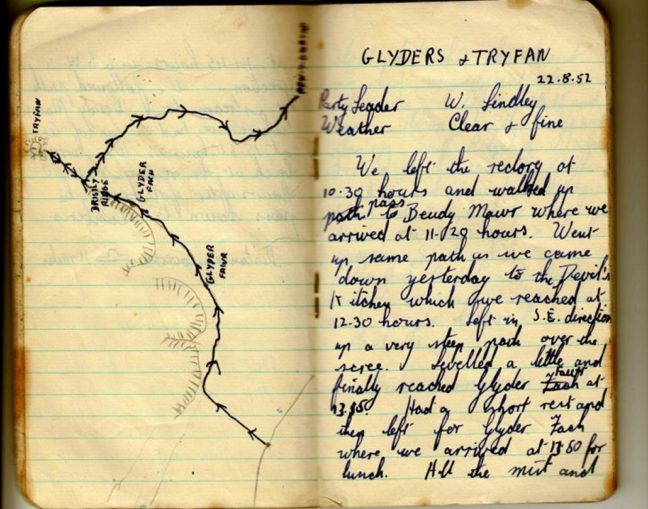

Part of the training provided by the Rev J H Williams was the importance of keeping records so I duly bought a small notebook, pen and pencil, and made notes of expeditions and his lectures that he called Yarns. (I now realise why I’ve used that word in these sailing articles) . I still have the notebook and it is now a treasured possession from my early youth.

My own observation was that Hemp was nearly as inflexible as sisal and kinked like mad when wet

You’ll see the expedition log was made on the 22 August 1952 when I had become 16 so I must have gone back to Llanberis several years running after first camping there. I’m still amazed when I look at the log now – both Glyder peaks and Tryfan on the same day leaving and returning from the Llanberis pass after walking from town to the start of the steep initial ascent – Wow!

Nylon stockings were first made in 1940 and were much preferred by ladies to the finest Lisle variety available in the UK (a tightly woven fine cotton). But, before the early 1950’s even the most glamorous ladies could only get “Nylons” if they were friendly with an American GI posted here.

The material and other products made from it started to become more widely available in the UK by the mid 1950’s and I remember being absolutely stunned at the silky feel, flexibility under all conditions, elasticity and cost of my first nylon rope bought a few years after my early forays in Wales.

I don’t have space here to continue the story of my climbing days save to say the Black Cuillins of Skye were for me a scarcely attainable Nirvana for several years. I never did get to complete the expedition along their ridge but made several attempts on parts of it during summer holidays when I dragged my own young family all the way up there from Surrey to camp at Glen Brittle for a few days and then all the way south again at a time when most of the roads north of Loch Lomond were still single-track.

ALCHEMI’S 1997 VOYAGE

The foregoing digression is a suitable introduction to the next stage of the voyage because here I was again at the island of Skye some 25 years since I had last visited and this time moored in a yacht at the head of Loch Dunvegan. The castle there is the traditional seat of Clan McLeod.

We needed to get from the head of Loch Dunvegan to the other side of the island to reach Portree where the present crew would leave and I had arranged for a new one to join. How to get there?

North-about would be the easiest passage. South-about would lead to a problematic passage through the narrow channel between the island and the mainland from Kyle Rhea to Loch Alsh and then under the new bridge from the Kyle of Lochalsh to Kyleakin that replaced the ferry I had so frequently used in my climbing days.

Norman had bought his return plane ticket valid for one particular flight only and was keen on the northern route because it was less likely to be affected by bad weather or some other delay. I was keen on the southern one because I had never been down the eastern side of the ridge into Glen Coruisk. Michael wasn’t fussed either way as long as he didn’t have to walk too far. It wasn’t easy resolving these differences. In the end I had to become Judge as well as Advocate and decided upon south-about (I don’t think I was acting like Captain Bligh on a bad day and Norman wasn’t a Christian Fletcher so there was no Mutiny and in the event we reached Portree in time anyway).

The wind was stronger the day we left Dunvegan and we raced down the loch until rounding the headland to face a southerly force 4 and seas to match. The wind-vane self-steering came into its own as we laboriously and wetly tacked around the high headlands of north western Skye until reaching Portnalong’s harbour in Loch Harport and dropping anchor just as it was getting dark.

The wind was just as strong when we set off on Tuesday morning and we decided to motor sail to begin with because the planned passage was a long one.

That took us to Loch Brittle and deeply poignant memories of many years earlier when camping with my young family on its shores.

The eastern shore and Soay Island now provided shelter from the strongest gusts as we sailed into and down the Sound of Soay.

The anchorage on Soay’s northern coast looked inviting but it also looked full with two yachts and two fishing vessels already present.

Rounding the headland into Loch Scavaig we were rewarded by the wind dropping and the cloud lifting from the peaks.

Concern about the forecast gale dissuaded us from anchoring there, where we would have dearly loved to linger. Instead, a gentle zephyr wafted us around the Point of Sleat, past Mallaig and onto another visitor’s buoy at Inverie in Loch Nevis.

These buoys were laid by the local publican so we felt honour bound to visit “The Old Forge” the following day and sample his wares.

In 1997 this Inn claimed the title of “Remotest Pub in Britain” but we couldn’t agree a price for T-Shirts emblazoned with that logo and left without increasing the contents of our wardrobes.

Sailing up the Sound of Sleat and into Loch Hourn was again delightful with magnificent scenery all around. We anchored near their juncture in Sandaig Bay and woke the following morning to another perfect day.

The narrow passage from Kyle Rhea to Loch Alsh is one of those, common on the West Coast of Scotland, that have extensive bodies of open water at either end. This invariably leads to large differences in time and maximum depth of water at opposite ends of the channel leading to fast currents as water sloshes backwards and forwards as the moon passes round the globe.

The result in the Kyle of Rhea is that maximum water speed at peak Spring Tides is a little above 12 knots bringing with it similar problems to those in the Pentland Firth, except that here the danger from high waves is replaced by the one of being swept uncontrollably onto the rocks on either side.

Another effect is that the time between high currents in one direction and similarly high ones flowing in the opposite direction is very short. Passage through such places therefore has to be made in a period of slack water lasting about twenty minutes.

We were a little earlier than planned at the southern entrance to Kyle Rhea and the ebb tide was still running at about 3 knots causing some of the back eddies and turbulence that must be very strong indeed at maximum flow.

Today however there was a useful and steady breeze allowing Alchemi to power forward under sail for three quarters of the length until we had to switch on the engine to pass the lee of a hill and escape into Loch Alsh before getting caught in flow in the opposite direction.

We replenished supplies in the Kyle of Lochalsh but there was too much swell and too many boats at the quays for our taste so we went on to anchor round the corner whence there were splendid views of Raasay Island and beyond.

It took us only a short time the next day to cross the Inner Sound and go up Raasay Sound to find a buoy in Portree Harbour.

Norman and Michael confirmed their travel arrangements on Friday and we were up betimes on Saturday morning in order to be at the bus stop in Portree at 06:50 after two dinghy trips taking them and their luggage ashore one at a time. The bus would take them to the Kyle of Lochalsh where they would change to another going to Glasgow whence they would catch a plane south to London and complete the journey to their respective homes.

I went back on board and bed to catch up on lost sleep.

To be continued …………….

© Ancient Mariner 2021